Take, Lord, receive . . . my memory.

—Ignatius of Loyola

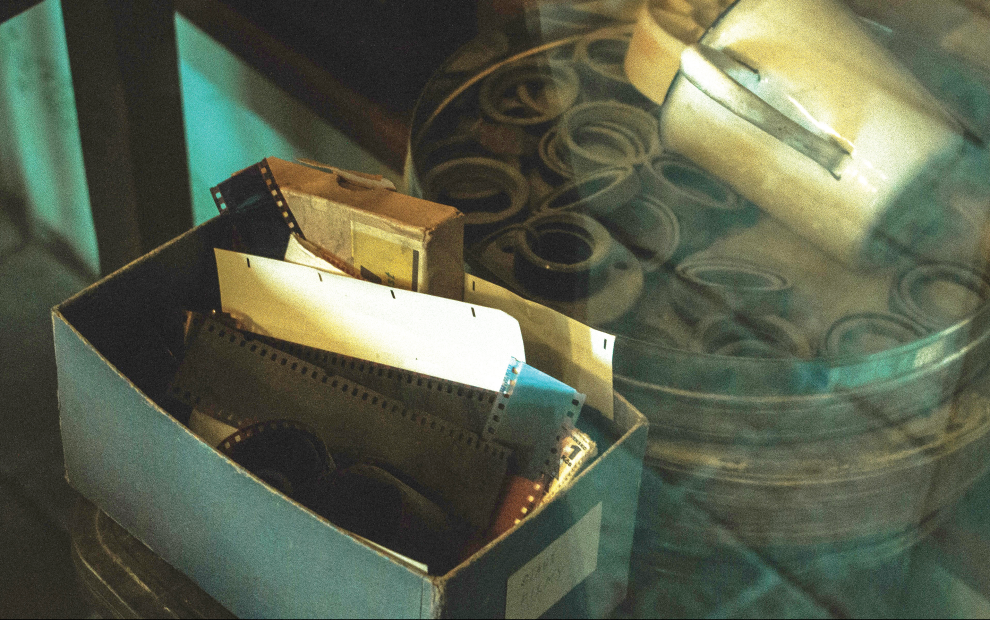

As kids—up to seven of us sharing two bedrooms—we were each Mother-apportioned one cardboard carton in which to keep our precious paintings, postcards, and projects. One box for all the papers of all the years considered worthy of being posted on the refrigerator door, if we’d gone in for that kind of proud display, which we didn’t. The appropriate appellation for this life-collection was “my box” or “your box.” Privacy prevailed; no snooping. But once the box was full, options were limited: prioritize and discard, though as a teen I skirted the issue by finding a bigger box.

In the dark of my bedroom closet, I still keep remnants of my childhood box, now transferred to a vintage picnic basket, no longer fit for its intended use because of its broken handle. Grammar school report cards. Felt insignias for orchestra participation. My grandmother’s funeral card. A junior-high classmate’s obituary. I peruse a stapled batch of oversized construction paper titled “My Book.” All but one of these kindergarten crayon drawings—a circus tent—illustrated my parochial world: a car parked in a garage, a church and steeple, a set-and-ready picnic table, fire trucks (my Dad volunteered), an American flag. The center page revives my pained offense at the teacher’s guess that the drawing of a round fishbowl stocked with goldfish and snails was an X-ray view of my mother’s purse.

At the foot of her bed, Mother kept a wooden box the size of a small cedar chest for linens, though it was unfinished pine that she hid under a makeshift slipcover. I was allowed to sit on it while watching her braid her hair, but no one was permitted to open it. It was Jimmy’s box, deluxe model.

Jimmy. Firstborn son whom I never met, nor he me, though we didn’t miss by much. I was in utero, due any day, when he was hit by a car while out sledding with his sisters. Killed in the deep midwinter. Buried on his ninth birthday. I responded to the trauma by digging in my heels: I was born weeks late at 10 pounds.

To me, Jimmy was a stranger, rarely named in conversations. Even so, the white-shirt, open-collar boy was never far away, framed in three ovals on the mantel. There was the gold-plated vase engraved with his name that held a single rose every weekend. Then there was Jimmy’s box, never opened, unlike Mother’s other pine chest, stacked with old fabrics for never-made dresses.

When Mom and Dad moved to their last house, Jimmy’s box was placed in an upstairs guest room. Late some night when I was home, I opened the lid. I didn’t delve into the lower layers but saw the clothes that lay on top. I figured all my siblings had similarly trespassed, but one afternoon I discovered that this wasn’t true of Rachel, the ever-obedient oldest.

After Mom died, Rachel and I were both at home. On some hurried mission, I ran upstairs where I found her in the hallway, standing wide-eyed, mouth agape.

She didn’t speak. I did. “What’s wrong?”

She stammered a vague phrase that I could easily interpret. “His coat.”

“Oh . . . yes. She kept it. You’d never looked in the box?”

“No. She said not to.”

But now she was absent and chaos was seeping in, like rain through a bad roof.

And then Dad died, too, and every corner of every drawer and closet called for inspection. We siblings all gathered for a work weekend, knowing that everything in the house had to find a new home or go.

We didn’t know it, but Mother herself had kept a big box of memorabilia—a perforated strip of postcards bought on her high-school trip to Washington; the script of her senior play, in which she was “the heroine” (not to be confused with the protagonist); her great-aunt’s published poetry; her high-school graduation program; college letters; and revealing diaries. And, though I’m sure he didn’t know it, even Dad had a box—report cards, a ninth-grade research paper titled “My Vocation,” his high-school diploma, and letters from his no-nonsense mother.

Monday afternoon, we poured mugs of coffee and made a ceremony of sorting to the bottom of Jimmy’s box, not preserved by him personally, as ours were, but by Mom as a memorial. She’d kept the clothes he wore when he was hit—blue plaid coat, yarn mittens, laced shoes—his school books, his baby book, his last ration book, his Cub Scout badges, a Christmas ornament he had proudly bought for the tree, a papier-mâché puppet he’d molded. We saved what anyone wanted, token mementos to move to our closets till someone sorted through them who never knew Jimmy.

At the sight of a collapsed red rubber toy, my sisters collectively gasped, a flash of recognition: Flipper. On lakeside vacations, the siblings had all mounted and batted the blow-up seal. But then they’d abandoned the balloon as belonging to Jimmy, who had without intention abandoned them for a small coffin in a silent grave or for paradise, their viewpoint changing like adolescent moods.

Moderator Rachel also pulled a majorette’s baton and a white dress from the box. “He played dress up,” Norma tearfully explained. That last winter he’d been Frosty the Snowman carrying a cane in that get-up. Or maybe, she later puzzled, the Littlest Angel, lost to Earth, landed in heaven.

A few weeks before Jimmy was killed, the neighborhood school turned down the cafeteria lights for an annual showing of an animated movie version of The Littlest Angel. I don’t remember the film but rather the picture book, shelved in the boys’ room.

If you got past the big words—aureate, Elysian, vociferous—the plot was simple: An unnamed boy had died, though you had to figure this from indirect phrasing; he “presented himself to the venerable Gate-Keeper” of heaven. Homesick, bored, and afraid, he, now known as the Littlest Angel, quickly “became the despair of all the Heavenly Host.” He sang off key. His halo wouldn’t stay put. When nervous, “he bit his wing-tips.”

Finally, he was called in to be disciplined by an “Angel of the Peace,” a nice guy who asked the tyke “what would make him most happy in Paradise.”

“There’s a box,” he said. “Back home. Under the bed. If I had it, I’d be happy—and good.”

Request granted. With that small box of familiar treasures in hand, the little one settled into and thrived in this unfamiliar realm. When opportunity arose, he added his commonplace box and all that was therein—a yellow butterfly, a blue egg, two river stones, and a keepsake dog collar—to the array of heavenly gifts presented to the newborn Christ child. And then the box itself was transformed. God-deemed the brightest and best of the baby-shower gifts, it lit up the eastern sky as the Bethlehem star.

Sorting through my parents’ house, I thought we’d find the dog-eared picture book. Maybe with the Christmas decorations kept in vintage suitcases, no longer fit for their intended use because of their broken handles. Maybe shoved in the back of a bookshelf. It wasn’t there.

The last morning of our marathon sweep, my older brother—Jimmy’s boyhood bedmate—by himself ceremoniously committed to the earth anything unclaimed in Jimmy’s box, burning the books in the backyard barrel and burying the clothes and toys in the brush along the creek.

The pine box he put in his car. He says it’s empty in his attic, close by but out of sight, where it will stay as long as his memory lives. As for me, I brought home Jimmy’s baby book and put it with mine in my box.

Take, Lord, receive . . . my memory. . . . You have given all to me. To you, Lord, I return it. All is yours; dispose of it as you will. Give me your love and your grace. That is enough for me.

—Ignatius of Loyola

This article also appears in the November 2023 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 88, No. 11, pages 24-25). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Unsplash/Diane Picchiottino

Add comment