In 2017, a Renaissance masterpiece by Leonardo DaVinci titled Salvator Mundi, which depicts Christ as the savior of the world, sold for $450 million dollars. The art market, a place where the extremely wealthy can invest their finances knowing their investment in “blue chip” artworks are not only secure but may yield a significant profit in time, may care little about the subject of this painting. After all, consider that this “savior of the world” who was sent “to bring good news to the poor” (Luke 4:18) has here become a commodity benefiting only the wealthiest and most exclusive members of society. Meanwhile, the United Nations World Food Program reports the shocking statistic that 828 million people in the world live in situations of hunger, with 50 million of them near famine (where $1 a day could provide up to two meals).

Are we to conclude that art and, dare I say, religion are just more “products” to be sold in a world economy that values objects more than people? Given the harsh realities of poverty and injustice in our world one might easily answer yes. Yet artist, theologian, and Claretian priest Maximino Cerezo Barredo has spent the better part of his more than 90 years answering this question with a resounding no.

Cerezo Barredo was born in Villaviciosa, Spain, in 1932. Two great loves would come to define his life: art and faith. He joined the Claretians, a Catholic missionary religious order (and the publishers of U.S. Catholic) dedicated to living and proclaiming the gospel, and was ordained a priest in 1957. He then studied fine art and embarked on a long career of painting and teaching sacred art.

While accumulating numerous accolades over his career, Cerezo Barredo experienced a formative period when he was sent with a group of Claretians to minister in Peru. There, in a small chapel in Juanjuí, something happened. While painting a massive 124-foot mural in the chapel depicting “salvation history,” he observed a peasant woman looking at one of his paintings.

“That woman, when she reached the end of the mural, found a figure crying over the death of a child, a woman who looked like her and whom I had painted,” Cerezo Barredo says. “Then she stood still, took out a candle and began to pray. Not to a saint, but to a dead child. To her son, perhaps. I thought at that moment that it would be absurd if I stopped painting. I could unite the priestly with art.”

Experiences such as this, working with various base ecclesial communities struggling with poverty and injustice while historic church gatherings occurred at Medellín and Puebla, helped focus and solidify Cerezo Barredo’s vision. His art and his work became rooted in the biblical message of liberation.

Theologies of liberation begin with situations of suffering. Inspired by biblical images of God from the book of Exodus and Jesus as depicted in the Christian scriptures, liberation theologies explore the social implications of a God who hears and responds to the cry of the oppressed. These images of God are not static but rather dynamic and active. As theologian Elizabeth Johnson succinctly states, “in situations of misery God is not neutral.”

A significant aspect of theologies of liberation is their praxis orientation. Modeled upon the God who “hears the cry of the poor,” these theologies begin by responding to concrete experiences of suffering. They then bring the work to eradicate injustice into dialogue with scripture and tradition. The fruit of this theological reflection is then brought to bear upon the ongoing work of justice. This becomes a progressive cycle uniting theology and the work for justice.

Cerezo Barredo’s reflection on uniting his experience of someone suffering with his art and priestly ministry attests to this orientation in his own work. But how can art liberate in an art world built to make art into a commodity, often regardless of subject matter?

Roberto S. Goizueta develops a “theological aesthetics of liberation” in his book Christ Our Companion (Orbis Books). He argues that to resist the commodification of religion and artistically rendered religious symbols we need to maintain the “intrinsic interconnections among doctrine, symbols, and practices.” Impressively, Cerezo Barredo’s art has long upheld this ideal.

One powerful way that Cerezo Barredo has resisted the tendency to commodify art, which can distance it from the lives of its intended community, is by making many of his drawings copyright free and available to all, especially his drawings for the three-year liturgical cycle.

Thus, in word-of-mouth fashion, his work becomes widespread through photocopies, reaching communities far and wide. Each drawing gives him the opportunity to highlight values important to the base ecclesial communities where he ministers and to stand against oppression.

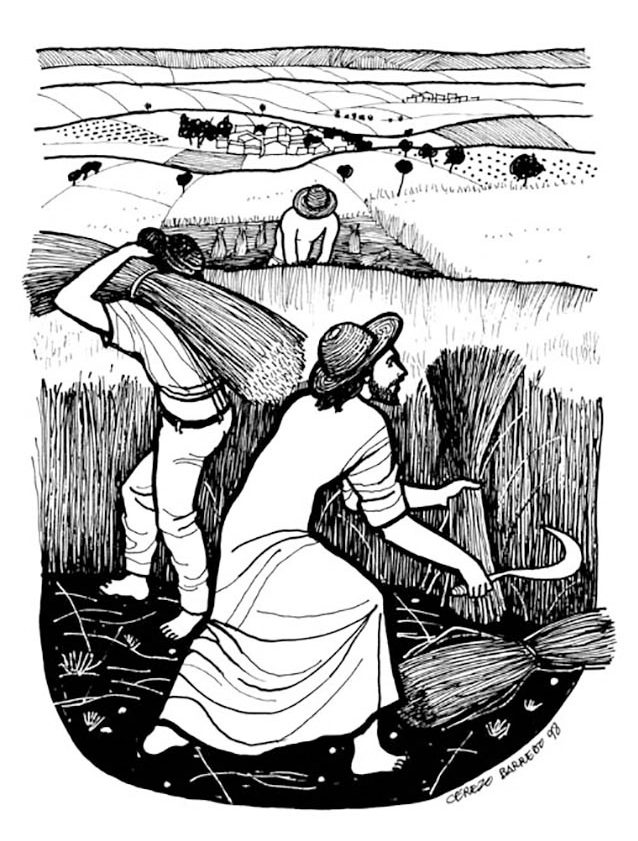

Consider his drawing from the 11th week in Ordinary Time, Cycle A. The gospel passage for this day is Matthew 9:36–10:8, where Jesus sends the twelve on their first mission to proclaim the kingdom of God in word and in deed. Cerezo Barredo chooses to envision a passage in Matthew 9: “The harvest is abundant but the laborers are few; so ask the master of the harvest to send out laborers for his harvest” (37–38).

In this drawing abundant fields stretch out beautifully before the viewer, unsullied by corporate greed. Rows and rows of crops are just waiting to be harvested, with plenty of food for the community. Jesus, recognizable in the foreground from other works in the series, isn’t just “moved with pity for the crowd,” as it says in the reading. His sleeves rolled up, wearing a hat to protect him from the heat of the day, he instead joins the group, swinging a scythe and gathering wheat. This is no far-off God, but a God with dirty hands and bare feet accompanying the workers in their daily labor. The message is not about some distant realization of the kingdom of God, but the beginnings of it in their midst, with Jesus leading the way.

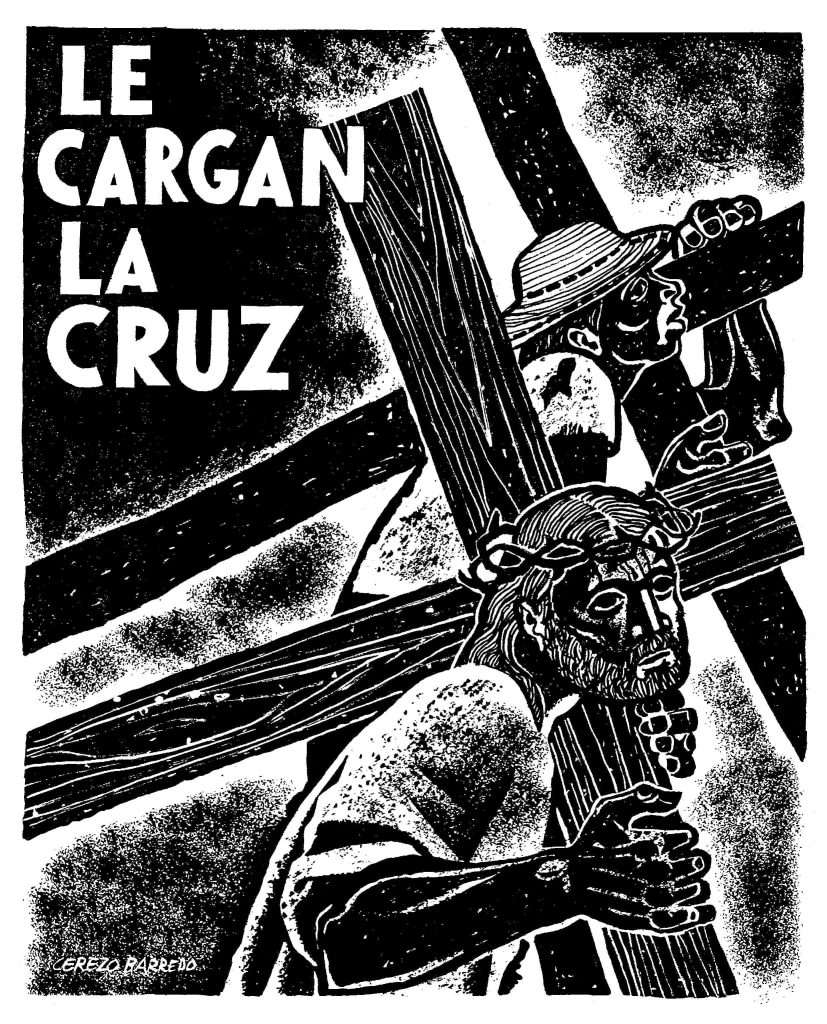

As the lives of Óscar Romero and so many other Latin American martyrs attest, resisting oppression and standing up for justice puts one’s life in peril. While some critics may consider depictions of the suffering Christ a manipulative means to convince people to “take up their cross” and endure their own sufferings, Christ on the cross takes on a different interpretation when viewed from the perspective of the oppressed. Here Jesus is in solidarity with those who endure horrific oppression and violence. The Christ who rolls up his sleeves and works alongside the people is also the Christ who is arrested on trumped-up charges and unjustly executed.

Consider Cerezo Barredo’s drawings from his Viacrucis series. In Le Cargan la Cruz (“They Carry the Cross”) this solidarity is made glaringly clear. Christ is not the only one carrying a cross. Indeed, the focus is not singly upon Christ. Instead the focus is on “they” who carry crosses. Likewise significant is the modern dress of one of the people carrying a cross in the drawing. The hat and T-shirt and even the open interpretation of the gender of this victim of violence helps Cerezo Barredo’s audience see themselves in these struggles.

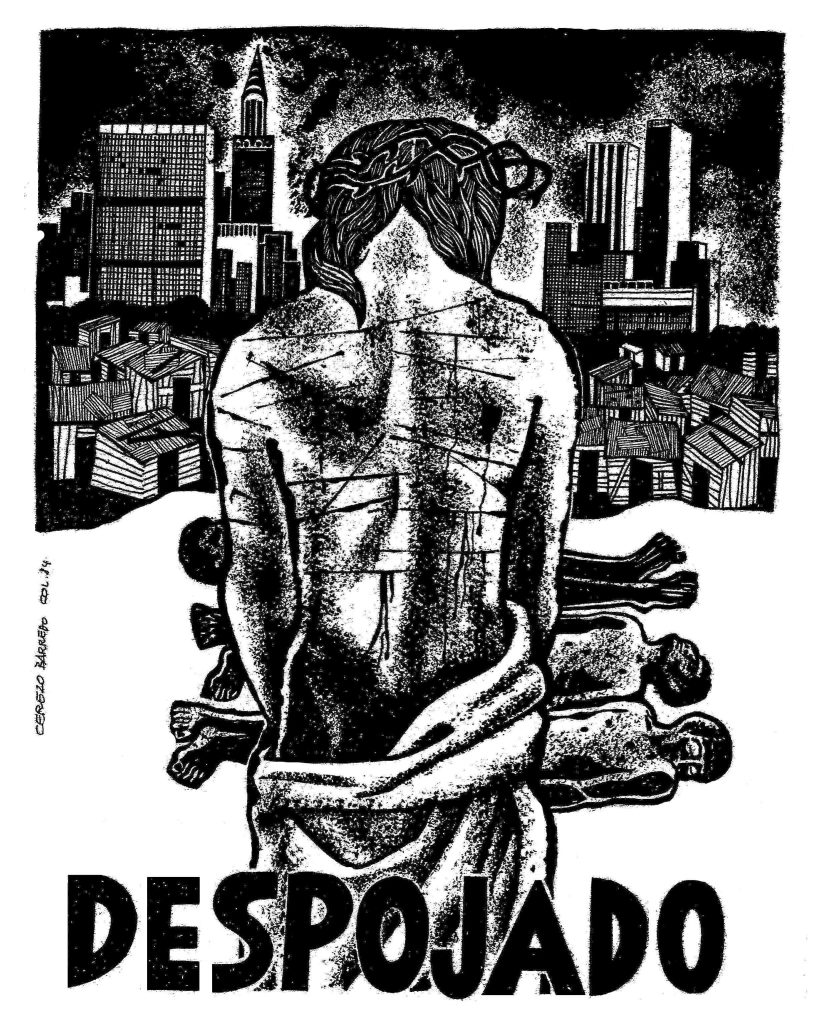

Despojado (“Stripped”), from the Viacrucis series, also challenges. This evocative image makes it clear that Christ’s sufferings are unfolding in his people today. In the 10th station Jesus is stripped of his garments. Yet here, “to be stripped of” or to have something taken away from you takes on social and economic connotations.

Christ stands before a tragic scene. At his feet lies a row of dead bodies. In the distance, an ominous metropolis of metal and glass skyscrapers tower over a makeshift city of humble wood houses—a scene of vast discrepancies of wealth repeated all over the world. Jesus has been stripped of his garments, revealing his bloodied, whiplashed back, but what else has he been stripped of? His people? The hope of a better future?

Consider another translation of despojado, which could mean “bereft.” Dictionary definitions of bereft such as “deprived or robbed of the possession or use of something” or “lacking something needed, wanted, or expected” make powerful connections with the image. In this light it is the people who have been stripped. They have been stripped of their dignity, their opportunities to flourish; ultimately, they have been stripped of their lives. The perpetrators of this violence may be faceless in this image, but the drawing forces us to see the consequences of individual and corporate decisions and policies that care little for the dignity and flourishing of human life.

Beyond resistance, hope is needed. Cerezo Barredo also creates stunning murals that actively resist the objectifying consumerist culture and provide hope. In his murals you see not only the beauty and scope of his vision but also a deep connection between belief, symbol, and practice realized within local community contexts.

Whether in a rural chapel or a cathedral, Cerezo Barredo’s murals make present God’s preferential option for the poor. Drawing upon the Latin American mural tradition, he weaves narrative and vibrant color into powerful, often inspiring, cultural messages for the people. Continuing his theme of Christ with the people, he painted an artistic and theological masterpiece titled En la Cena Ecológica del Reino (“At the Ecological Dinner in the Kingdom”). Here Christ sits in nature with a diverse gathering of 12 disciples aging from infant to adult.

The title and Jesus’ post-resurrection wounds help us know that this is an eschatological image. So it is with great interest that we observe the details of this heavenly banquet Cerezo Barredo envisions. Here we see humanity living in harmony with creation from sunrise to sunset; nature flourishes and grows, with dead tree stumps offering new sprouts; and the wisdom of Indigenous peoples keeps the community grounded. Men and women of all walks of life offer their learning as they gather around a table filled with local cuisine of bread, water, wine, plantains, and more. Christ, who looks like the people he serves, warmly draws the community together, honoring the dignity of each person at this heavenly banquet.

In murals such as this and his impressive mural in the Catedral de la Prelatura de São Félix do Araguaia, Cerezo Barredo shows the breadth of his theological and artistic vision. It’s not just about the struggle against injustice and walking with those in need, as important as those are. It’s about the complete realization of the kingdom of God and the flourishing of each and every person. In fact, Cerezo Barredo’s vision expresses communion with all of God’s creation.

Cerezo Barredo chooses to paint this message in murals, a medium difficult to be bought and sold. The point is not that all art should be free. The artist, like Jesus working alongside the people, is entitled to a just wage. Instead, Cerezo Barredo’s art strives to emulate a more Christ-like way of being in unison with the community. He portrays a way rooted in the God revealed in sacred scriptures, a God who hears the cry of the suffering. This is a way neither ignorant of nor stifled by injustice. Instead, it is a way that shows both solidarity and hope.

Pondering these images, some people might think, “Let’s include them in our lectionaries or our next presentation.” As laudable as that is, the message might be deeper. Cerezo Barredo’s art and ministry encourage local artists to use their talents to proclaim God’s liberating message of salvation in their own unique contexts to inspire positive change. This is art of the people, not beholden to an art market. Images of this type will not only resonate much more deeply with the local community but will also teach the wider church just how grand a vision God has for salvation.

Cerezo Barredo’s art of resistance and hope is therefore more than an exemplary model of inculturation and mission. It is a blueprint for enlivening a global church that truly values each local community and their experience of God’s liberating presence. His art and ministry tells each of us, “Use your gifts to build up your community; they need you!”

Whether art, advocacy, accompaniment, or protest, each person has a gift to use to build the kingdom. What is important is finding your unique voice to offer resistance and hope. It could be a painting or it could be political office. It could be small but more intentional choices in your daily life and letting solidarity and justice inform your decisions. Whatever the case, Cerezo Berrado’s work proclaims that you are essential in building God’s kingdom in the here and now.

This article also appears in the November 2023 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 88, No. 11, pages 10-15). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

All Images by Maximino Cerezo Barredo

Add comment