A long time ago in a Midwestern state far, far away, I gave a talk in a parish gymnasium. A crowd of patient parents, squirming children, and older folks with nothing better to do on a wintry morning sat before me on cold metal folding chairs. Had these people been warned I’d been brought in to comment on the Advent readings? It seemed a hopeless assignment: the wrong audience in an uncomfortable venue. Maybe they’d secretly come for the coffee and cookies. I began by asserting that Isaiah is everybody’s favorite prophet, our go-to seer for a season of anticipation. Off the cuff, I added: “Not like there’s much competition. No one’s exactly rooting for Habakkuk.” From the back of the room, a voice piped up. “I am!” a middle-aged woman declared. “Habakkuk’s my guy!”

I dubbed the woman “Habakkuk,” and for the rest of the morning we did call-and-response on matters of dueling prophecy. She was a great sport, and it made for a more playful experience for everyone. But later, back home, I wondered how anyone could get excited about an obscure Hebrew prophet such as Habakkuk. He only shows up twice in our lectionary—on an autumn Sunday every three years, and on a summer Saturday every other year—which means some years we don’t hear from the seer with the funny name at all.

The kicker is, both times Habakkuk appears, it’s nearly the same passage: different verses from Chapter 1 of the Book of Habakkuk paired with the same verses from Chapter 2. It’s unfair, considering this prophet only gets two shots at speaking to us. Maybe we’re not missing much. Habakkuk’s prophecies are only three chapters long, which means you can become an expert on his writings pretty quickly. Not so with Isaiah, whose thought encompasses 66 chapters. By comparison, Habakkuk’s a fellow who gets to the point.

The more I thought about my new friend “Habakkuk” up there in the frozen north—perhaps the church’s biggest fan of an odd little prophecy—the more I wondered if I was missing something. After all, this seer is intriguing for a lot of reasons. Habakkuk’s the rare prophet who’s “self-summoned”: initiating the divine conversation rather than the other way around. And it’s clear from the start that he’s mad at God—for all the right reasons. Habakkuk’s generation is full of violence and bad actors. Why does God allow this? If God is infinitely powerful and just, why not stop the bad guys in their tracks and make peace a reality, for crying out loud? Habakkuk is the one crying out loud.

Of course, every generation has its share of violence and bad actors. On a given day, you or I might do a pretty good Habakkuk imitation in our private thoughts. Why does divine justice allow Vladimir Putin to invade Ukraine? Why can just about anyone pick up a gun and shoot random strangers? Why is God so quiet in the face of evil, when even sinners like us can see that a little smiting of evildoers would be helpful now and then?

Habakkuk accuses God of negligence: “Why do you simply gaze at evil?” (1:3, NABRE). He flatly tells God the divine law is “numb,” since it changes nothing. This resonates in a nation like ours, whose leaders righteously promote the Ten Commandments in public yet rarely abide by them. The hour of evil seems to have no challenger.

God doesn’t disagree. In an unnerving reply to the prophet, God agrees things are bad and going to get worse. More violence is on the way. What’s especially curious is that God doesn’t punish or even scold Habakkuk for his audacious attack on divine justice. Neither does God ignore him. God engages the conversation and seems willing to make room for the bluntness of a person on fire with questions and complaints.

This frank exchange has counterparts elsewhere in the Bible. Moses shares this sort of relationship with God: a friendship that values and respects the right to speak without censoring the content. Job also engages the divine without a filter, interrogating God one minute and accusing God the next. In fact, most Wisdom books in the Bible—think Job, Ecclesiastes, Psalms, Sirach, and the Book of Wisdom—demonstrate a remarkable willingness to question received religious teaching and to wonder if it’s a mistake to accept what we’re told, particularly when it doesn’t square with our experience.

What’s weird about Habakkuk is that his objections seem to be in the wrong part of the Bible. Moses, after all, had a unique relationship with God unparalleled in the Hebrew scriptures. He and God spend 40 years together dragging the deeply uncooperative Israelites through the desert. One could argue that gives Moses a pass to speak his mind. And the Wisdom tradition is a scripture set apart. Coming late to the biblical party in the centuries before Jesus, this literature exists precisely to reconsider old teaching in a fresh light.

Prophecy, meanwhile, has other fish to fry. A prophet is the mouthpiece of God. Prophets deliver God’s words to the leaders of the people. They’re not commissioned to question divine judgment or to get in God’s face about stuff above their pay grade. Habakkuk is basically a prophet who doubts like he’s a Wisdom writer and talks like he’s Moses. He’s anachronistic in both directions at once. Only the prophet Jeremiah, in his ranting and lamenting, escapes his role and genre with such deliberation.

God makes a strange offer to Habakkuk: a vision that contains five woes. Biblical woes are nothing to sneeze at. These are curses that will come to pass if we cross a point of no return in our conduct. The woes are leveled against the arrogant, the presumptuous, the violent, the decadent, and the idolators, respectively. We can all produce lists of folks we might assign to these groups, but let’s not forget the ways in which our egos, thoughts, words, lifestyles, and values make us eligible for similar judgment. The woes demonstrate what Jewish scholar Abraham Joshua Heschel describes as the mystery of God’s anger, which is central to the book. Habakkuk may be plenty angry about injustice, but that doesn’t come near to the divine outrage for what happens to the defenseless in our world.

This is where I begin to appreciate my Midwestern friend “Habakkuk” and why she feels passionately about these prophecies. Habakkuk is a tradition buster all the way around. He speaks before he’s spoken to. He’s a prophet railing against God’s passivity. And then he tosses centuries of covenants out the window. He does this by refusing to pledge fidelity to God for the usual reasons: for land, prosperity, descendants, or protection. Instead, Habakkuk promises to devote himself to God for no reason whatsoever. Think about that: loyalty with no conditions! If you have a friend like this, consider yourself fortunate.

Knowing God is as fierce about justice as he is makes Habakkuk’s heart literally sing. He delivers the spectacular conclusion of his prophecy in song. Habakkuk declares: I don’t care if the trees don’t bloom, the fruit doesn’t bud, the harvest fails, and the herds are lost. Even if the world falls apart, God is still my God.

This radiant confidence raises questions for me. What kind of strings do I attach to my loyalty to God? How far off the rails can this generation go before I give up on prayer? Will I continue to sing God’s praises even if my world falls apart?

This article also appears in the October 2022 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 87, No. 10, pages 47-49). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

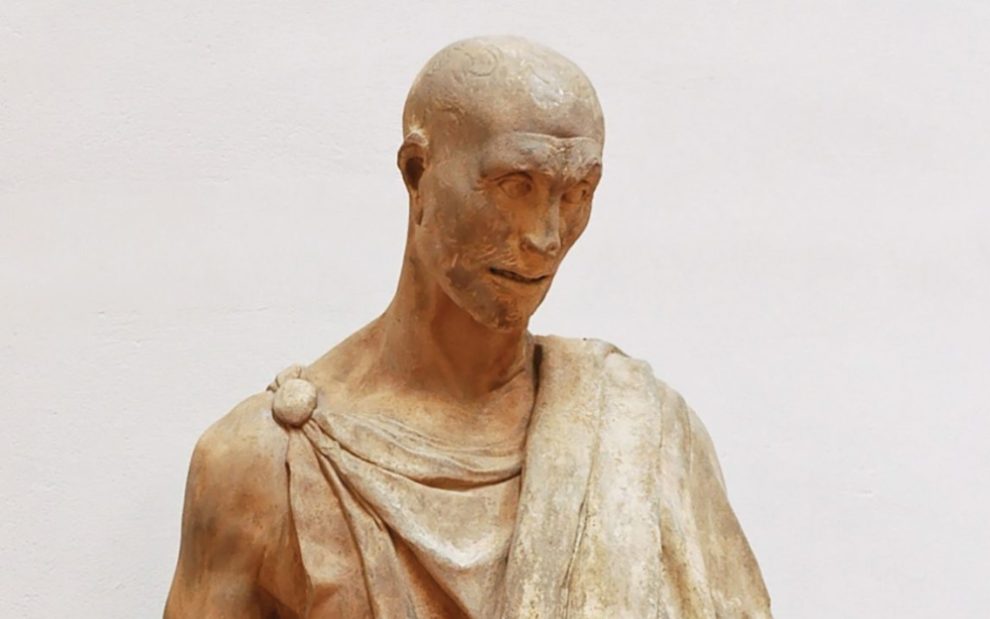

Image: Wikimedia Commons/ Zuccone, Donatello, 1423.

Add comment