San Francisco–based artist Stefan Salinas, whose webcomic The Sacramental Father Dom tracks the everyday life of a priest, never doubted his vocation. “From as early as I can remember, as soon as I could pick up a crayon, I was drawing. I would think of stories, mostly influenced by science fiction,” he says. “I wanted to be the next George Lucas or Jim Henson. But even then, I didn’t think I could deal with a huge project like a movie. Working solo as an artist or comic book illustrator seemed more attainable.”

Salinas also can’t remember a time when he wasn’t a spiritual seeker. Raised in the modern spiritualism in Texas, he describes his parents as believing in a higher power as well as in reincarnation and communication with the dead. “From an early age I was searching—in my art I always showed fantasy worlds and other planets, but religion was always present,” he says. “I was interested in the art, music, and architecture of established world religions.”

While studying painting and fine art at the University of Houston, Salinas developed an early interest in creating illustrated books. “I’d do my paintings in series, trying to give a bigger picture of a character. I wanted an audience to see a whole story line,” he says.

Due to his general interest in religion, a college friend urged him to join the Unitarian Universalists, and he was a member for 14 years. “When I moved from Texas to San Francisco in 2000, I got very involved with the Unitarians,” he says. “They are socially active, very much into causes and human rights and listening to people with different opinions. But in my personal experience, if I wanted to dive deeper into studying one particular religion’s philosophy, people could get uncomfortable.”

In 2011 two events led Salinas to convert to Catholicism. Influenced by a good friend, he joined a circle of early morning Mass attendees. When his friend asked him if he’d been baptized, he initially replied, “Why would I want to do anything like that?” Nevertheless, he kept getting up early for daily Mass.

Around that same time, Salinas became a volunteer art director for the Blind Vietnamese Children Foundation, a nonprofit founded by a priest named Father Thuan and run by Catholic sisters. “I was really witnessing the deeds of Catholicism, not the words. That made an impression on me,” he says. “Befriending priests and seeing how hard they work made a difference. But there were also some very coincidental experiences and dreams that seemed to give me answers and point the way. I know that sounds a little ‘woo,’ but they helped seal the deal inside and out.”

As a gay man, Salinas faced some challenges in converting to Catholicism, but he was grateful to find a welcoming community in his home parish, San Francisco’s Most Holy Redeemer. “Joining the church wasn’t the easiest path. Dealing with the wider church can be a struggle,” he says. “But most people don’t know that when AIDS hit San Francisco in the 1980s, the first AIDS hospice was started by the Catholic Church. That helped in my conversion. Most Holy Redeemer has a history of transforming the community. People are excited to be there. Many of them left the church and came back. Some were kicked out of their families, and then they found a church that welcomed them.”

For Salinas, art provides a way to study the spiritual paths of other Catholics. “Currently, the challenge for me personally has been how much I identify with being a Catholic on the outside versus on the inside,” he says. “I want to focus more on being a Catholic on the inside. I want to identify with the deeper truths. Art, music, theater, even movies help me almost as much as what I get from Mass in drawing closer to God.”

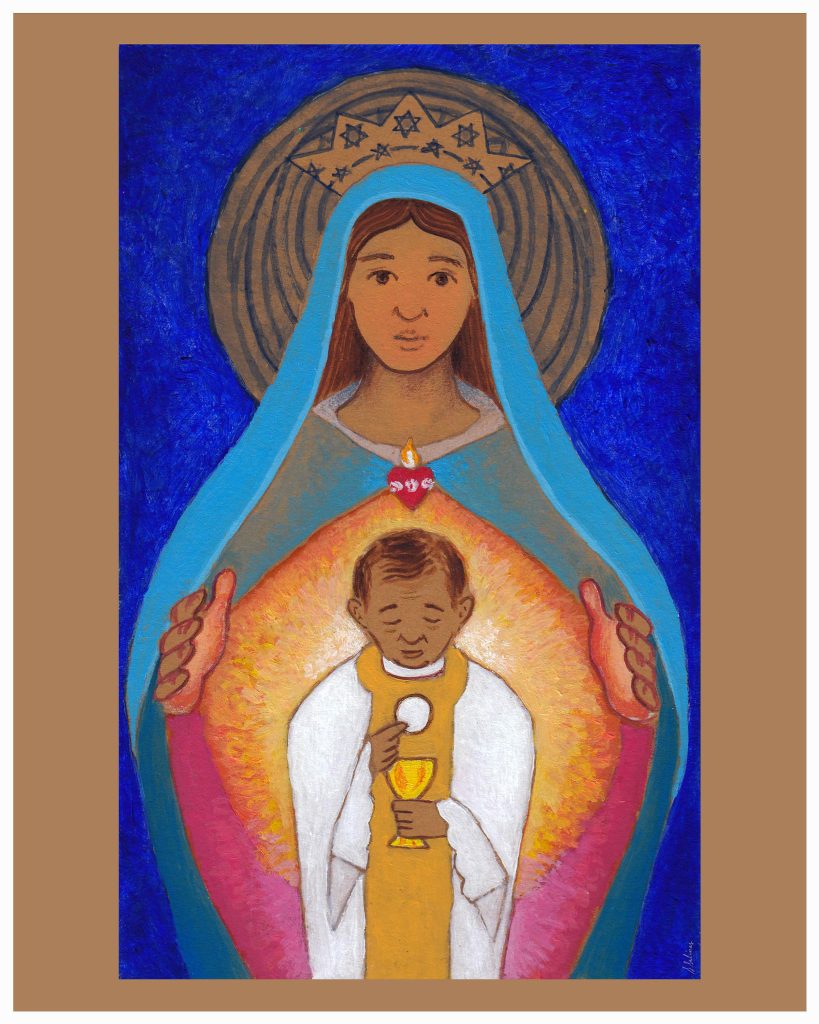

Soon after converting, Salinas began making signs, banners, and murals for churches. “I love the idea of a structure meant to help us get in touch with the immaterial and beyond. A church is a house meant to point us beyond itself. That is so fascinating to me,” he says. “It’s beautiful to have an art piece in a museum, but it’s even better if you have an art piece that helps people get in touch with something higher. What more can one do?”

The more, as it turns out, is a webcomic intended to humanize priests. Nine years in the making and based on many interviews with real priests, The Sacramental Father Dom tells the story of a fictional priest’s everyday life. “The word sacramental refers to a handkerchief used to wipe the chalice. This character feels like he’s a person but is supposed to be more than a person. He feels he’s put into a box, a chalice or tabernacle,” Salinas says. “My inspiration was my friend Father Bernie, who has since died. We would meet for coffee, and he dressed a lot like my character. I learned a lot from anonymous interviews with priests and people who worked with them as well as from stories that landed in my lap. Some priests said they can’t even be completely honest in the presence of other priests.”

Salinas says that for many priests, the vocation brings a certain amount of loneliness. “Often priests live alone in a rectory, far from family, and they work on holidays. Their family becomes the secretary, the custodian, parishioners who invite them to their homes—this is especially the case for diocesan priests. When someone leaves a parish, it’s like having a granddaughter leave home,” he says.

Salinas hopes to show the sorrows and joys priests live through with complexity and humor. “A friend of mine was shocked once when he heard a priest tell a dirty joke. I found that heartbreaking and touching. I said, ‘He’s a human being.’ People who previously saw priests as a cutout or caricature now see them as my character, Father Dom,” he says. “Some people who’ve left the church tell me they wish real priests were like Father Dom. I say, ‘They are.’ ”

Salinas’ day job in the secular world allows him to pursue the artistic projects that inspire him most profoundly. While he has done some secular art, his focus is on working within the church. Right now, he is working on a mural celebrating Pope Francis’ 2015 encyclical Laudato Si’ (On Care for Our Common Home) in a university ministry office at the University of San Francisco. “I’m excited that our current pope is concerned about these pressing issues, but the encyclical is dry and academic,” he says. “I thought, how can this reach people better? I looked at their websites. I wanted to put meat on the bones to get the word out. These projects help me to not get so frustrated over the political divide and other issues. I like focusing on something I can do rather than what I can’t.”

In talking about his faith, Salinas displays the “zeal of a convert” in the best possible sense—the passion of someone who has tried many paths before finding the one that feels true. He recalls a dream he had of a complicated, ornate Persian rug, which he saw as representing the Catholic Church. “I was on the fringe of this rug. But all the different parts have colors, shapes, and different perspectives; they are all part of a larger whole. Each point of view had something to contribute and something to learn,” he says. “The dream helped me see myself as part of ‘Here Comes Everybody.’ Time and time again, Jesus reaches out to someone he’s not supposed to talk to. Jesus stands on the outside and connects with outsiders.”

This article also appears in the August 2022 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 87, No. 8, pages 45-46). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

All images courtesy of Stefan Salinas.

Header image: Portrait of Stefan Salinas standing in front of his mural at St. Philip the Apostle’s School in San Francisco, 2015.

Add comment