When a young woman in an Alabama parish heard that the Jesuits of St. Louis were organizing a solidarity stand vigil, she was inspired to arrange something similar at her parish. The women religious she consulted guided her to Leslye Colvin. Colvin, a long-time social and racial justice advocate, was supportive of the idea, but suggested the need for a complementary educational component. An educator and facilitator in the JustFaith program, Colvin recommended the parish participate in JustFaith’s new Faith and Racial Equity program.

Initially, the parish’s pastor agreed to both the vigil and the program but then received pushback from the parish council. When he withdrew his support from the vigil, Colvin suggested they move it to the courthouse. For two months Colvin and others have met there for an hour each week in a prayerful vigil culminating in a litany of names of those murdered in acts of state-sponsored violence.

Colvin was not surprised by the pushback.

“After the glitch with the vigil,” she says, “I decided to personally pay the parish’s registration fee for the Faith and Racial Equity program. When the pastor again rescinded his support after promoting the program in the parish bulletin and on social media, we had to find another way to move forward. The pandemic has revealed new ways for us to be and form communities of faith beyond the walls of the parish. This led me to reach out to women on Catholic Women Against Racism with hopes of finding participants. Within less than 24 hours, enough women responded to form our first group beginning in January as well as a second group to begin in the spring.”

Anti-racist action seems to be such a vital component of Christian witness in our culture, so why do so many Catholics seem uncomfortable with it?

“Raising the issue of racial injustice within the context of the church or within other social systems that identify with the dominant culture will result in pushback from the majority,” Colvin says. “People who benefit from living in white bodies are challenged by discussing the privileges received from having white bodies. The desire for white body privilege was the impetus for the flawed social construct of race.”

People who benefit from living in white bodies are challenged by discussing the privileges received from having white bodies.

She continues by saying, “Even with the context of American Catholics, there are differences in how those of us with Black bodies process scripture. When we hear the story of bondage in Egypt and God tell Pharaoh to free God’s people, we hear the same words spoken to those who have and continue to oppress us.”

Colvin’s experience is representative of a broader issue in the Catholic Church in the United States. Recent years have brought us to a crisis moment, when we as a culture and as individuals must ask ourselves how we will meet the challenge of racial injustice.

Catholic responses to this question have varied. Many Catholics seem content to carry on our prior legacy of complicity with racism, even going so far as to silence anti-racist activists of color or oppose racial justice initiatives.

Yet Catholics of color continue to speak out, and some of their white brothers and sisters are listening.

It has become clear to many that working for racial justice is part of a life of Christian faith and morals that transcends political and theological divisions. The Solidarity Stand vigils are just one way Catholics are addressing the need for racial justice reform. The USCCB formed their Ad Hoc Committee Against Racism in 2017. Georgetown University, which once owned and sold slaves, started its Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation as part of its recognition that atonement and reparation are called for. Loyola University in Chicago has created a database for anti-racism resources, and the Academy of the Holy Cross established an anti-racism and social justice advocacy team.

However, anti-racism programs in parishes are an especially important part of the racial justice movement among Catholics; They take place where individuals and families interact communally, and where so much racism and bigotry have taken place, in the past as well as the present.

Anti-racism programs need to be a part of every parish’s agenda, but how to implement such programs and determine what will work best for which parish is an ongoing process.

St. Vincent de Paul Church in Philadelphia recognized the need for racial healing on the parish level as early as 1997. The parish provides an account on the Catholic Common Ground Initiative of the painful process they went through as they began addressing racial justice issues. Their testimony is a reminder that anti-racism work is not likely to be easy. Indeed, if it feels as though it is going too smoothly, it might be a good idea to ask what’s being left out.

Anti-racism programs need to be a part of every parish’s agenda.

Advertisement

Anita Foeman, a Black diversity trainer, presented St. Vincent de Paul with materials detailing the process of anti-racism collaboration.

“The first stage is superficial pseudo-community—polite niceness, where no one steps on anyone’s toes or raises difficult issues,” she says. “People want to avoid conflict or the perception by others that they are prejudiced or overly angry.”

Stage two, she continues on to say, “is chaos and emptiness. This comes when people determine to break through the superficiality, voice their opinions, and face the real issues that racism raises. Conflict emerges. Emotions of anger and trepidation come out. Participants feel that they are going backward, away from loving community. The problems raised seem overwhelming or unsolvable. But if people can hang on through the ‘chaos’ stage, undergo self-examination, share fears and vulnerabilities, admit prejudices, express willingness to change and speak the truth in love, chaos can give way to stage three—real community.”

Those involved in the collaboration at St. Vincent de Paul, initially upset and inclined to quit, eventually understood that the pain they were experiencing meant they were moving in the right direction. Any parish or community engaged in similar collaboration would do well to keep this in mind.

Anti-racism action in parishes is more common now, thanks largely to the activism of Black Catholics and their allies.

Christ the King Catholic Church in Nashville is one church that instituted an anti-racism initiative, which includes providing media resources to parishioners and forming a reading group that discusses such works as Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow and Bryan Massingale’s Racial Justice and the Catholic Church.

Especially powerful are the testimonies about racism the parish shares on their website. However, all the authors are white or non-Black persons who realized their own complicity in white supremacy. As a white Catholic, I found that these witnesses compelled me to work better at my own ingrained inclinations towards racism—but I also felt Black voices should be centered more.

In Seattle, the historically Black Immaculate Conception Parish recently collaborated with Jesuit St. Joseph’s Parish to create the Say Their Names visual installation, which raises awareness of and protests the many Black and brown persons murdered by state-sanctioned force across the nation. The installation consists of 30 signs, each bearing the name of someone killed by the Seattle police.

The Church of the Transfiguration in Pittsford, New York has extensive anti-racism resources available on its site, including visuals, links to stories about Black saints, educational material for parents of children and teens, and links to videos and articles. For Catholics who are frustrated with parishes in which racism is never or only rarely addressed, it is encouraging to see such a diverse array of material from both religious and secular sources.

However we go about the project of undoing racism, it’s vital to recall that for Catholics the issue of racial justice goes beyond the social or political.

Donna Becher of Blessed Sacrament Parish in Charleston, West Virginia says that she found her involvement with anti-racism work hard but rewarding. Becher said that her parish is mostly white, but that there are a few Black, Latino/a, and Filipino families there as well. A women’s restorative justice group in her parish organized a reading group to study Robin D’Angelo’s White Fragility, and Becher participated.

“I think it was effective,” she says. “The book was hard to read for some, but we were very honest about it. In our honesty, we acknowledged our difficulty with Robin D’Angelo’s material and tried to sort through our own individual fragilities.”

However we go about the project of undoing racism, it’s vital to recall that for Catholics the issue of racial justice goes beyond the social or political. It is touches on our obligation to bear witness to the gospel in our personal lives and in how we choose to shape the culture around us.

It’s not enough simply not to engage in acts of overt racism; we must be vehemently and creatively engaged in collaborative work to oppose racism in all its forms, wherever it is found—including within our own hearts. Failure to do so is a failure to follow Christ.

So, how can Catholic laypersons and religious start to engage in this work? Here are several suggestions.

- Start with prayer. If you anticipate animosity from your pastor, parish council, or fellow churchgoers, an invitation to prayer might be the best opening. This might be as simple as requesting that prayers for racial justice be included in the Prayers of the Faithful. You could also suggest that parishioners join in novenas to end racism or organize prayerful vigils.

- Write to your church leaders. Especially if racial justice issues are in the news, contact your parish and diocesan leaders and ask them if they are willing to make a statement in favor of racial justice. You could request that petitions for racial justice be included in your parish bulletin.

- Write to your diocesan newspaper. You can also make your appeal to church leaders public with a letter to your diocesan paper. Should the paper opt not to print your letter, consider making it public using social media or contact a sympathetic journalist to help you raise awareness of the need for racial justice in parishes.

- Distribute material. Even if you are uncomfortable approaching parish leaders directly, you can still access material about anti-racism work and share it either online via your social media platforms or physically in the form of pamphlets or informational sheets.

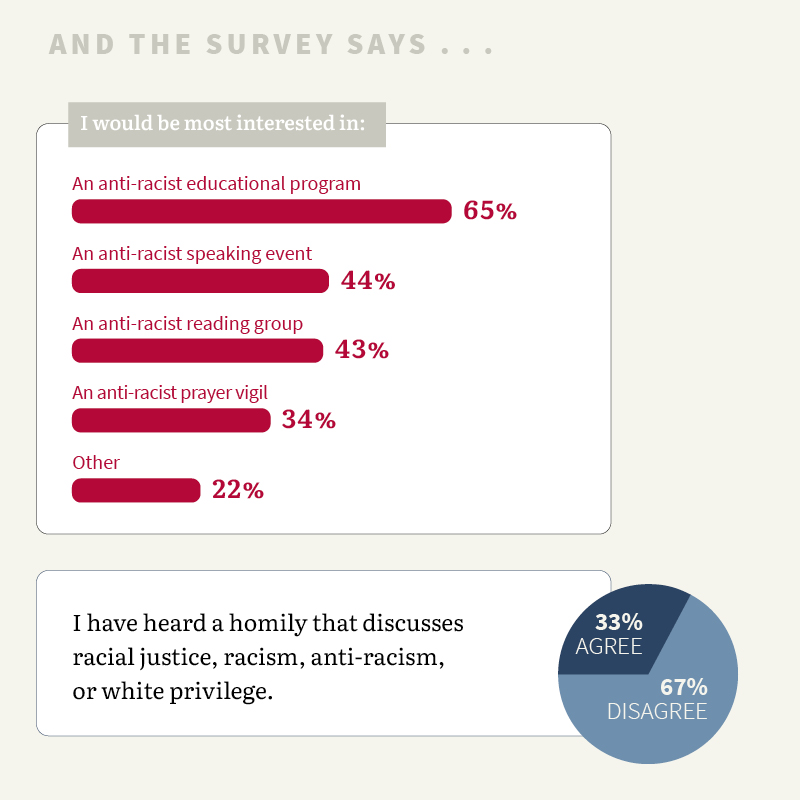

- Explore educational programs. The kind of program needed may depend very much on the nature of the parish. Diverse or predominantly non-white parishes may want to focus on programs that can help them raise community awareness of anti-racism as a Christian obligation. White-dominant Catholic parishes likely need to start with working on anti-racism in their own circles. See what anti-racist educational programs are available online or via communication media.

- Organize reading groups. White parishioners organizing these programs should consider asking non-white Catholics to take leadership roles but must also be wary about asking persons of color to educate white Catholics out of their racism. Consider taking a collection to reimburse any non-white Catholics involved in organizing or leading these events.

- Invite speakers of color. If possible, bring in speakers and influencers who can give a witness to the gravity of racism and the gospel calling to oppose it. Actual personal encounters can be valuable in helping others understand that racism affects real living human beings, our fellow children of God.

Image: Flickr/Catholic Church England and Wales

Add comment