Tom and Fran Libous had been through plenty of rough rides in their 40 years of marriage and his 14 terms in the New York State Senate. But nothing matched what confronted them in April 2016, the seventh year of 63-year-old Tom’s battle with prostate cancer.

“A team of doctors at Sloan Kettering told us there was nothing else they could do,” Fran says. “They said, ‘You need to go to an inpatient place.’ ”

A nurse herself, Fran protested that surely she could take Tom home and care for him—until a doctor escorted her into the hallway and out of Tom’s earshot. He quietly explained that now was the time to let trained hospice professionals manage Tom’s pain and ensure his comfort. Fran should spend her remaining time with him as his wife, rather than as his caregiver.

She reluctantly acquiesced.

Hospice accommodations could be found near the hospital in New York City, but the extensive Libous clan lived hours away in Upstate New York. Fortunately, a new residential hospice facility called Mercy House of the Southern Tier had just opened one month prior in the Binghamton area, and it had a room for him.

Less than a week after he entered Mercy House, Tom said, “I think I’m going to die tonight.” Fran held him through the next hours, and he passed in the morning.

“He didn’t really have pain or suffering,” Fran says. “For that I will be eternally thankful.”

Always a place of mercy

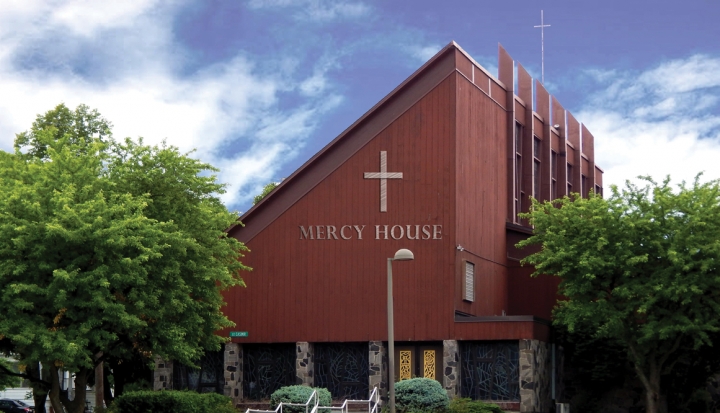

Housed in the former St. Casimir’s Roman Catholic Church, Mercy House opened three years ago, its name echoing Pope Francis’ designation of 2016 as the “Year of Mercy.” It’s a community care shelter that offers 10 beds to people of all faiths who need end-of-life accommodation.

The structure’s previous purpose as a place of worship foreshadowed its current function. St. Casimir’s stained glass windows remain as part of Mercy House, some depicting the corporal works of mercy.

“One of the corporal works of mercy is taking care of the dying,” says Father Clarence Rumble, whose vision led to the creation of the facility.

As church buildings shutter their doors, some meet with the wrecking ball. Others become arts centers, mosques, senior housing, or other venues. According to Georgetown University’s Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate, 18,224 parishes were alive and well in 1970. By the end of last year, that number had plummeted to just over 17,000. Plenty of former churches could be repurposed into hospice facilities. So far only a rare few have.

Beginning his tenure in 2008 as pastor of the Church of the Holy Family in nearby Endwell, New York, Rumble appreciated the enthusiasm the parish showed for overseas missions. But he hoped that passion could be applied closer to home. So he issued a challenge: “What are we doing for people here?”

He related his experience with an aunt who had made her transition under the care of hospice professionals at Francis House in Syracuse, some 80 miles away. Asking the local Lourdes Hospice agency if such a residential facility would be beneficial in this area, he heard a powerful “Yes!”—an answer that soon resounded through the parish and the community.

Tender care for many

“When people come in the door, they know how they’re going to go out,” says executive director Linda Cerra.

More than 349 residents have transitioned from Mercy House after an average stay of about 34 days. None of its 10 beds stays empty for long.

“We knew there was a need,” Cerra says. “How great of a need we had no idea.”

Residents may come to Mercy House at the end of their lives, but staff and volunteers make sure it is a place of love, light, and laughter rather than darkness.

It sometimes got downright rowdy when rambunctious, street-savvy Phatar, 12, spent his final days there. Despite his ever worsening condition, he bopped from room to room, greeting other residents while nonchalantly dropping the “f-bomb.”

His memory, like that of so many others, will live on in the hearts of those who served him at Mercy House.

So will that of Father Nick. He had been relegated to spend his last days in a nursing home when Rumble brought him, already fully bedridden, into Mercy House.

One day Father Nick announced to his startled aide, “I want you to get me up and wash me up. I am saying Mass today.”

He delivered the homily, went into the dining room, had a glass of sambuca with his meal, and went back to bed—and died the next day.

“There have been so many miracles here,” Rumble says.

Those miracles can be witnessed on a daily basis in the 270 volunteers working at a computer, behind a broom, at the stove, or at residents’ sides.

“It takes 160 volunteers to run Mercy House every week,” Cerra says. “They do four-hour shifts, sometimes three times a week. Last year volunteers gave 25,320 hours.”

Helping hands

For 2½ years, Doug Parks has served as a volunteer companion, and he is learning to be a caregiver.

“People serve people in need,” he says, summing up Mercy House’s mission. “God calls us to love one another. It’s nice to be family when [people’s] family can’t be here, and a lot of people don’t have family.”

Society has changed, he points out. Many people follow their jobs to distant points and can’t drop out of their lives when loved ones need end-of-life care.

Mercy House opens its arms to any and all who need it.

“It’s not about religion,” says Parks, a former university police officer and associate pastor at a Nazarene church. “It’s about unconditional love and support through difficult days.”

Fellow volunteer Sheila Smithgall, who gives her time at the reception desk, agrees.

“There’s a lot of dignity and spirituality here,” she says. “I give love, and I get it back. I am really blessed to be here.”

Mercy House offers a physical embrace: bedrooms with cable TVs and phones, lovingly prepared meals served to residents and their guests, and around-the-clock TLC. Lourdes Hospice, which began caring for the dying in 1980, provides end-of-life care through its team of professionals. Its costs are covered by Medicare.

Nationally, 4,300 hospice care agencies served more than 1.4 million Medicare beneficiaries for one day or more in 2016. Most of these patients received hospice services at home, with about 43 percent spending their final days in a nursing or hospice facility, according to the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. Sixty-three percent of those agencies identify as for-profit.

Lourdes Hospice accepts Medicare dollars, but Mercy House itself does not. Nonprofit and funded solely by donations, Mercy House accepts donations from residents and their families, but no one is turned away for lack of resources.

The community proves itself ever eager to help, purchasing items such as toilet paper, batteries, and coffee pods from the wish list on Mercy House’s website. A local florist delivers fresh flowers for each room at no charge every Wednesday, and restaurants deliver free homemade soup. Schools, service organizations, and local companies hold spaghetti dinners and other fund-raisers, and local philanthropic organizations have given grants to meet specific needs, such as a new boiler.

Eighty percent of the facility’s $1 million annual budget comes through memorial donations, supplemented by two main fund-raisers: the Tony DelNero Memorial Golf Tournament, named for an early fund-raising volunteer who died unexpectedly, and the “Gala of Taste,” a giant cocktail party, wine tasting, and food sampling with a live auction and entertainment.

Laughter and love

Although people whose loved ones died at Mercy House are discouraged from immediately volunteering, that’s exactly what Joani McCarthy did. Her sister, Michelle Malinovsky, was one of Mercy House’s first residents. While Michelle rested quietly in her room, McCarthy helped Rumble make shepherd’s pie in the kitchen. Now she and her crew are responsible for every Tuesday’s “Italian Night,” bringing in ingredients they’ve purchased to treat diners with homemade gnocchi and other savory delights.

A gentleman whose wife passed at Mercy House now brings in tomatoes from his garden and has begun working in the kitchen himself.

The meals are so good they should start a Weight Watchers chapter at Mercy House, jokes Rumble.

“One resident gained 30 pounds while she was there,” he says of a woman whose health kept unexpectedly improving. “She didn’t qualify for hospice care anymore, so she went to a nursing home.”

Tiffany Steinruck has seen the whole gamut of human emotions under Mercy House’s roof. A residential care aide there for three years, she has witnessed many residents, particularly as they near the very end of their lives, speak conversationally with unseen visitors.

“One lady gave up her baby for adoption, and she [told an unseen guest], ‘I regret it.’ It took her a long time to come to peace and finally cross over,” Steinruck says. “We’ve had family members watch a Bruins game with chicken wings and beer, hooting and hollering and opening a beer for their loved one, even though he’s dying.”

Thankful for Mercy House

Dorothy Sisson breathed a heavy sigh of relief when she learned that Mercy House had space for Kenn, her husband of almost 50 years. Diagnosed only a few months prior with stage IV pancreatic cancer, Kenn had spiraled into almost total incapacity in front of Dorothy’s terrified eyes.

“I had asked that he be put on the waiting list [for Mercy House],” she says. “Things took a turn when he became bedridden.” Lourdes Hospice does assessments and can hasten admission for those individuals who can’t remain at home, depending upon bed availability.

Dorothy suffers from arthritis in her back and though Kenn had lost a lot of weight, she still could not adjust his body without excruciating pain. Kenn was clearly experiencing his own agony due to the cancer, and Dorothy felt helpless to alleviate it. And how could she go on living in their home if her beloved husband would die there?

One day, witnessing Dorothy’s struggles, Kenn used his remaining whisper of a voice to ask for his phone. With it, he called 911. Lourdes Hospice arranged a place for him at Mercy House.

“Now I could go home at night and sleep knowing he was well cared for,” Dorothy says. “I didn’t have to be awake, worrying. People [at Mercy House] were great, very caring, and very kind.”

Win-win for all involved

Raised as the daughter of a United Methodist minister, volunteer coordinator Ann Lomonaco stresses that being a practicing Catholic isn’t part of the equation in being accepted as a resident, volunteer, or employee. But being part of Mercy House has enhanced her spirituality.

“I see how we really are meant to care for the lonely and the sick,” she says.

One person who did that particularly well was Mercy House’s director of spiritual care and social work, Sister Joanna Monticello, who died unexpectedly in January of this year.

Atheist residents might groan when they saw a nun walk through their bedroom door, but Monticello’s big smile would disarm them. She’d make it clear she was there for light talk or TV, not conversion to Catholicism.

While Lomonaco was considering becoming part of Mercy House, friends told her it sounded like a really depressing place to work. But it’s not, she says.

“People are at the end of their earthly journeys, and now I see they are living their final days in a sanctuary,” she says.

One 50-something resident wanted to keep her shades drawn and her room darkened. She had been long estranged from her family and expected to die alone.

She wasn’t alone at Mercy House.

“We became her family,” Lomonaco says. “Two days [after she arrived] her shades were up and she was out in her wheelchair for breakfast.”

Watching unfolding scenarios of such soul-healing—and receiving the occasional heartfelt thank-you—is what feeds volunteers. Lomonaco regularly hears that they feel they get much more than they give.

Nevertheless, she wants them to get some special TLC too. She arranges the annual Volunteer Appreciation Dinner in Mercy House’s lower floor, where a DJ spins records and spearheads a noisy trivia contest.

Volunteers self-schedule from home via an online program, and Lomonaco sends out email blasts when time slots need to be filled.

That’s seldom a problem.

The staff polls volunteers with a confidential online survey annually. The 99 percent volunteer retention rate speaks for itself. Employee turnover is minimal as well.

Individuals with developmental disabilities shadow volunteers to sharpen their skills and contribute to the efforts at Mercy House. High school and college kids also offer their time and come away with depth they may not have gained elsewhere.

Always room for improvement

When Rumble started talking about creating a local hospice facility, Amy Roma started talking about leaving her employer of 32 years to join its staff.

A registered nurse, Roma has served as director of residential care since before the facility opened in March 2016. She loves her job, she says, but when pressed she says her biggest challenge so far has been the building itself.

“I would have laid it out a little differently,” she says. “A larger medication room, wider doorways to patient rooms, a larger aide station—it gets crowded.”

More closets would be helpful, and they could surely fill more than 10 rooms.

Some of these challenges are due to the building’s previous incarnation as a Catholic church. But when some people originally suggested building from scratch rather than repurposing the closed church, Rumble wasn’t a fan of the idea.

“[The building] was already existing,” he says, “and the architect said it was doable.”

Repurposing any church building into a hospice center would be a monumental task. To open the facility, the group had to first buy St. Casimir’s for $325,000 from the Syracuse diocese and then morph the circa-1969 church into 10 wheelchair-accessible and aesthetically pleasing bedrooms, a big kitchen, welcoming gathering places with plenty of soft couches and chairs, administrative offices, medical rooms, and a chapel.

Early on, organizers raised $400,000 in donations, which included a $250,000 grant from the Lourdes Hospital Foundation. The ultimate price tag was $1.2 million.

It could easily have been 20 percent higher, were it not for the kindness of so many discounted bills and free materials from both Catholic- and non-Catholic-owned local companies, Cerra says.

But beyond the nuts and bolts lies a deeper spiritual significance in renovating St. Casimir’s into Mercy House of the Southern Tier.

“People are hurt when a church closes,” Rumble says. “It helps them to know its mission is continuing.”

This article also appears in the September 2019 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 84, No. 9, pages 12–17).

Image: Courtesy of Mercy House

Add comment