“Find a place you trust and then try trusting it for a while.”

With these words, the first of Corita Kent’s “Rules,” she burst into my life as an impish, holy, and joyful maker, beckoning me to keep faith, to embrace uncertainty, to look deeply, and to festively affirm beauty.

Corita’s life and art brought encouragement just when I needed it. After 10 years of life, ministry, and putting down roots in Central Virginia, I had just moved to a motherhouse of women religious, following an intuition I hoped was God’s call.

Such a leap of faith is tough to explain to family, friends, and colleagues, many of whom assumed I would accept the promotion I’d been offered, pursue a Ph.D., or get married. In fact, I had assumed some of those things, too. Instead, I’d given up my orderly five-year plans, following instead the compelling divine voice speaking through nighttime dreams, silent prayer in the Eucharistic chapel, or a line of poetry. I had an unshakable sense that I had to get this religious life thing—which had existed inside me since early childhood—figured out. Instead of keeping “becoming a nun” as a vague possibility tucked in some out-of-the-way corner of my consciousness, I needed to either walk through the convent door or close it.

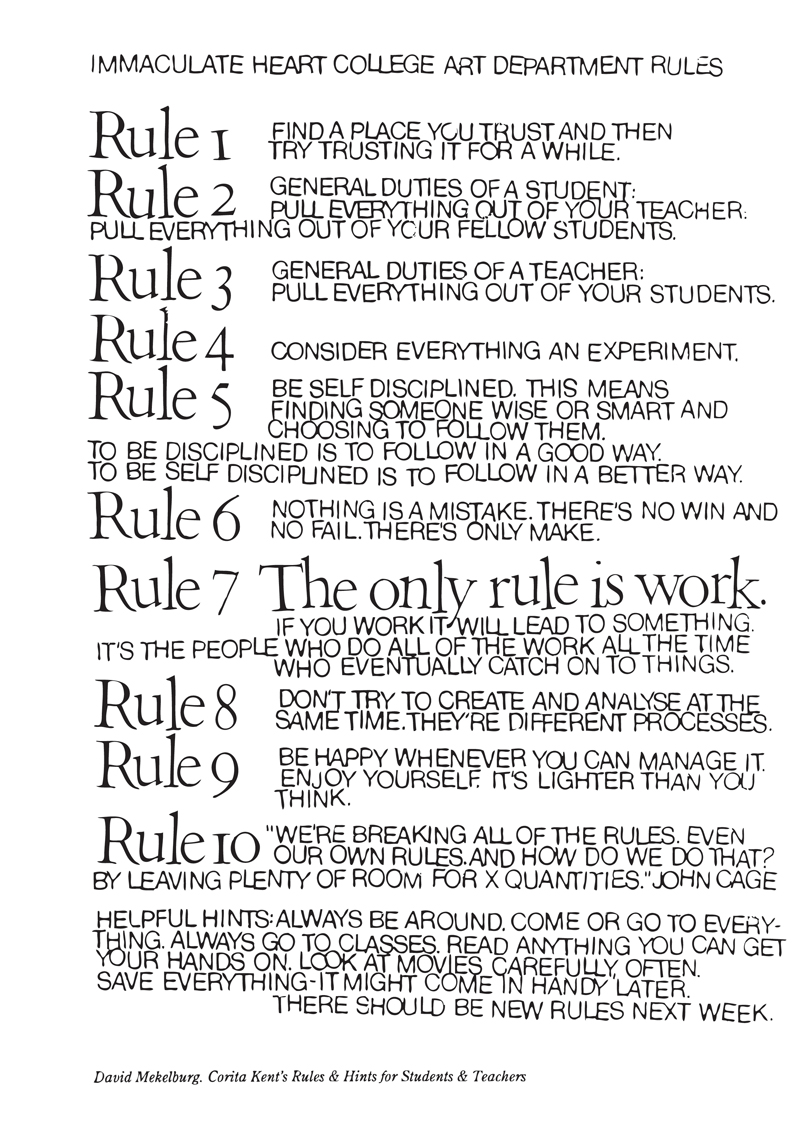

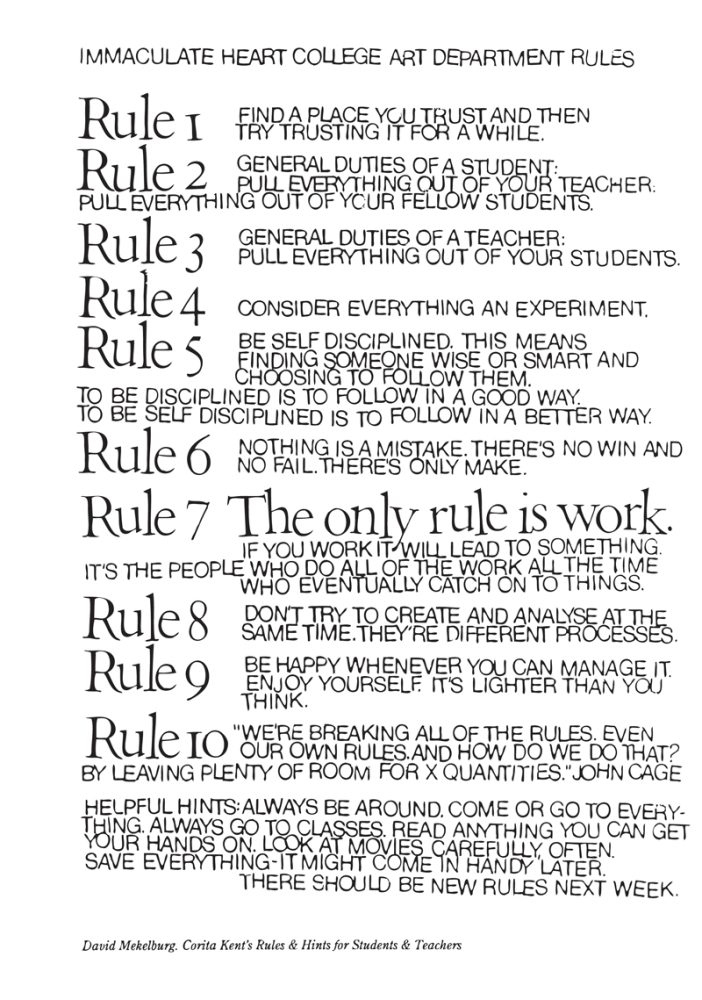

Corita—the “pop art nun”—entered the scene for me when I day-tripped to Pittsburgh’s Warhol Museum to see the “Someday is Now” exhibit. When the museum’s stainless steel elevator doors slid open, I faced an enormous reproduction of Corita’s “Immaculate Heart College Art Department Rules.” I stepped out of the elevator, feeling immediate consolation with the opening words: “Find a place you trust and then try trusting it a while.”

Corita Kent, Immaculate Heart College Art Department Rules, c. 1968, lettering by David Mekelburg, reprinted with permission of the Corita Art Center, Immaculate Heart Community, Los Angeles.

My smile broadened as I continued reading. A few favorites:

Rule 4: “Consider everything an experiment.”

Rule 6: “Nothing is a mistake. There’s no win and no fail. There’s only make.”

Rule 8: “Don’t try to create and analyse at the same time. They’re different processes.”

Rule 9: “Be happy whenever you can manage it. Enjoy yourself. It’s lighter than you think.”

Though I’d only taken two steps into “Someday is Now,” I’d found—or had been given—a guide for my continued leap of faith. Corita not only accepted uncertainty in art-making and life but also seemed to revel in it. Corita’s rules countered the internal and external voices nagging me about the decision to quit my job, leave home, and discern religious life.

Corita’s first Rule calmed these voices with a paraphrase of the guidance scripture repeats over and over: trust. Don’t be afraid. Don’t be anxious. Be still and know that I am God. Trust in the Lord. Try trusting for a while.

I spent the rest of the afternoon wandering through the exhibit of her bright, text-studded prints, never making it to the Warhol’s permanent collection. Though Corita eventually left religious life—as many did after Vatican II—that fact did not discourage me in my own discernment. It seemed clear she flourished in the life for many years and that it was in vowed religious community that she became herself, artistically and spiritually. Corita once mused, “Perhaps the words of [Pope] Paul VI to artists could then be descriptive also of sisters: ‘. . . creators, vivacious people and stimulators of a thousand ideas and of a thousand inventions.’ ”

Corita Kent, be (1st of 4 pts), 1967, of love (2nd of 4 pts), 1967, (a little) more careful (3rd of 4 pts), 1967, than of everything (4th of 4 pts), 1967, reprinted with permission of the Corita Art Center, Immaculate Heart Community, Los Angeles.

Looking long and lovingly

The “Someday is Now” exhibit offered creative exercises from Learning by Heart (Allworth Press), coauthored by Corita Kent and her former student Jan Steward. The book’s first chapter is titled “LOOKING” and features exercises to train the artist’s eye. One such looking assignment, aptly called “nothing is the same,” reads: “Take something in nature—two dandelions—and look at them for five minutes. List how they are different from each other.”

Corita trained her students to look deeply, even especially, at simple things. “Poets and artists—makers—look long and lovingly at commonplace things, rearrange them and put their rearrangements where others can notice them too,” wrote Corita. One way to learn this, she taught, was to observe a child’s response to the world around her “with the openness and curiosity it deserves.”

These exercises made me, in my muddle of discernment and self-doubt, ask: How do I look at the world? For me, at least, the answer is often in a rush, distracted by devices, overstimulated by the soundbite-driven news cycle. A worldview that values looking closely at two dandelions for five minutes—“a long, loving look at the real,” to quote Jesuit Walter Burghardt—is countercultural and prophetic.

Blindness and sight are a regular metaphor for conversion in scripture. Like the religious leaders judged by Jesus as “blind guides,” I get myself into trouble when I think I see but in fact don’t. The deep looking that Corita taught encourages “beginner’s mind,” reverent attention, and deep curiosity. This kind of looking is as much a spiritual practice as a creative one and draws us to find beauty in the everyday and reclaim our birthright of childlike awe.

Joyful play and the struggle for justice

Corita’s playfulness is another source of inspiration. Another Learning by Heart exercise advises, “Make a toy. Make it something you want to play with—just to please you.”

As theologian Harvey Cox notes, “In her own person Corita stands for a kind of festive involvement with the world.” She loved circuses and parties. Corita encouraged not only childlike looking but also play as part of the creative process, advising a blocked artist to “go to a movie, take a walk, read a book for fun.”

Yet for all her joy and delight, Corita did not live in sanguine ignorance of human pain and structural injustice. She was deeply engaged with the social realities of her day: the Vietnam War, race riots, poverty, and the nuclear arms race. She responded through art to the signs of the times.

Corita embodied poet Wendell Berry’s advice to “be joyful, though you have considered all the facts.” People who can truly dwell in both the identity of the committed activist with eyes wide open to injustice and suffering and the joyful reveler in the goodness of world are rare and precious.

Corita’s holding of this tension reminds me not to lose sight of joy, play, and celebration while in the trenches of ministry and justice work. Any authentic Christian spirituality holds the paradox between joyful celebration of creation’s goodness and redemption’s promise with deep awareness of profound brokenness and suffering resulting from sin. Great saints and great artists model this paradox, which is the ground of hope.

Corita Kent, love is hard work, reprinted with permission of the Corita Art Center, Immaculate Heart Community, Los Angeles.

Finally, love

Undergirding it all, I read in Corita’s work and life a fundamental commitment to love. For Corita as for St. Paul, without love, nothing else matters. My first year in religious life, I created a Christmas altar in our house chapel. At its center was a print by Corita featuring Beatles’ lyrics: “Love is here to stay, and that is enough.”

Significantly, several of Corita’s later works touched on the theme of love. An iconic 1985 postage stamp she designed with her characteristic splash of colors reads simply “love.” Another piece carries the message, “Love is hard work.” For Corita, as for that other great 20th-century Catholic visionary Dorothy Day, the final word was love. Also like Dorothy, Corita’s sense of love was not romantic and sentimental but prophetic, gospel-inspired, and grittily incarnational. Hard work, indeed.

Since I first encountered Corita’s art, my leap of faith has continued. I have entered religious life, becoming “Sister.” As I discern, I draw strength from the eschatological hope that marks her life and work. Corita’s life of prayer, teaching, art-making, and activism was driven by a future vision. Her commitment to looking deeply, facing evil and suffering while remaining joyful, and staying rooted in radical love were shaped by the vision of the reign of God: already-but-not-yet, the promise of a new creation, the truth to which all authentic lives point.

I will let Corita have the last word:

“Not only must the sister be active in making new her own immediate community, she must be able to see it as an integral part in making of the whole new world community. With great creativeness she will grasp at least some of the complex relations that exist among all people and all times as they move forward to the great party with the best wine (saved till last) toward which Christ’s first sign pointed. As a maker, she will rejoice to share in the making of the new creation.”

This article also appears in the March 2019 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 84, No. 3, pages 20–22).

All art reprinted with permission of the Corita Art Center, Immaculate Heart Community, Los Angeles.

Add comment