When people think of their favorite Catholic church buildings, the typical mid-century suburban parish probably doesn’t make the list. To theologian and religious historian Catherine Osborne, though, these are some of the most compelling churches in America.

“A lot of people don’t like modern churches, or at least they think they don’t,” Osborne says. “I have a little bit of a contrarian streak, so I was interested in why they got built in the first place.”

When Osborne started tracing the development of these churches, she discovered that they often either predicted or were inspired by the Second Vatican Council’s views on the role of science, community, and faith in people’s lives.

For example, Osborne says, before Vatican II Mass had been somewhat of an individual experience—the priest usually spoke in Latin and people often practiced their own individual prayer routines during Mass. The changes in liturgy meant that the Mass was used to develop a sense of community. Over time, this bled into church architecture.

Parishes, dioceses, and religious architects responded to this time of upheaval in liturgy and Catholic identity by creating church buildings that looked to the future rather than to the medieval past, designing everything from multiuse buildings to chapels on the moon and under the sea. As Osborne describes in her book, American Catholics and the Church of Tomorrow, some of these projects were more successful than others.

Why don’t people like modern church buildings?

There’s a very dedicated group of architects and architectural critics who, since the 1980s, have made it their business to mount a really serious critique against modern churches. They say that there are certain forms of architecture—Gothic, Romanesque, baroque, all those historical styles—that are timelessly Catholic. To steer away from these styles, then, is to steer away from a very important Catholic heritage.

For everyday Catholics, modern spaces often look spare. They are often not heavily decorated, and any stained glass or statues may be more muted than people are used to. People were intentionally steering away from darker stained glass and toward getting a lot of light into the church, and that’s different from what many people are used to.

Where did this shift in how churches look come from?

A lot of my book is about how many Catholics came to believe, along with much of the rest of the world, that evolution and adaptation were key facets of the universe. Everything evolves and adapts, and if you don’t also evolve and adapt, then you don’t make it. Whether or not people thought that was a good thing, they came to believe it was a fact.

Within the Catholic Church, there were two reactions to this. The first was, “We’re going to be the one thing that doesn’t evolve—the Catholic Church is timeless.” And the other was, “We may not change our beliefs about God, but we are going to move toward the future because that’s what life is. We follow a living God; we want to be a living church.” That meant people also started predicting that our worship style and worship spaces would have to adapt and evolve and change, too.

In the 1950s liturgists were pretty confident about what the future of the Mass looked like, but they didn’t anticipate it would change as much as it did after Vatican II. They did, however, predict that the assembly was going to be gathered around the altar more instead of sitting quietly in rows of pews and looking in the direction of the celebrant. So there started to be this movement toward semicircular and circular churches or churches in the shape of a fan or a Greek cross where people could get on three sides of the altar.

And then Vatican II makes a bunch of these expected changes but also sets off a whole set of discussions that weren’t anticipated. All of sudden in the 1960s and ’70s there is abruptly much less confidence about what the future of the Mass is going to look like.

In this atmosphere the idea of having an extremely adaptable and flexible worship space so that people can still use it in the future, no matter what happens, is very attractive. So architects started designing churches with folding walls, chairs instead of pews, and banners or rotating art instead of permanent art. In this way the parish could respond to different needs and situations.

Can you give an example?

I think the space that best exemplifies this moment is the Chapel + Cultural Center, the Newman Center and associated parish at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York.

The Chapel + Cultural Center was built in the mid-1960s as a multipurpose worship and arts space on the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute campus in Troy, New York. The building was meant to bring together the campus with the surrounding town: Not only does it house a parish, but it also includes spaces used to host concerts, lectures, and conferences open to all, combining sacred with secular space. In 2011 the building was added to the National Registry of Historic Places, the most recent building to have been recognized. Photo courtesy of the Chapel + Cultural Center, Rensselaer Newman Foundation.

When the parish built this building in 1965, they didn’t know what the future of the liturgy would hold. They also weren’t sure they would want a physical church forever. Maybe they would want to have Mass in different places or move out of town. So they tried to make a space that would be adaptable not just for liturgical uses but also for other uses so that the university or somebody else could use it if they did leave.

The space has a very fancy folding wall and a lot of moveable sanctuary furniture. You can move the altar as well as almost everything else. The whole building was designed around the idea of “We don’t know what the future of the liturgy looks like, or what the future of our community looks like.”

What else was going on in the mid-20th century that affected how churches were built?

Beginning in the 19th century there was an increasing conviction that evolution is how the world works. That conviction didn’t stay in the natural sciences but got imported into other areas as well, including art and architecture. A good building is adapted to its time and place and has a solid underlying structure (rather than just an attractive facade).

What this means is that church buildings have to use modern materials. There was a lot of technological development at this time, especially around the world wars, so architects had all these new materials available to them like concrete, plywood, steel, glass, and even plastics.

There’s also the beginning of an environmental consciousness. For example, it doesn’t make sense to build a church with a flat roof somewhere it snows a lot. Conversely you don’t want a steep-pitched roof in the southwest United States; what you need is something that is low and dark.

Can you give an example of a church that was built with these ideas in mind?

One of my favorite comparisons is two churches built in the early 1960s by an architect named Pietro Belluschi, an Italian immigrant: the San Francisco Cathedral and the Portsmouth Priory in Rhode Island. Both churches look completely different despite being built by the same person at around the same time.

The Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Assumption in San Francisco (here and in this article’s header image) is one of two churches built by architect Pietro Belluschi in the early 1960s. Belluschi designed the cathedral out of concrete to fit in downtown San Francisco, which was quickly becoming a technological hub. While many critique the building for its stark appearance, last year Architectural Digest named it one of the 10 most beautiful churches in the United States.

The San Francisco Cathedral burned down in the early ’60s, and they hired Belluschi to rebuild it. Today people are always telling me how much they hate it. It’s raw concrete, and it’s kind of dark. It’s very stark. Belluschi said he designed it to fit in downtown San Francisco in the financial and technological center of the city.

Meanwhile across the country he’s also building the Portsmouth Priory Church, which is also a modernist building but made out of different materials: fieldstone and a lot of wood. To Belluschi these materials seemed better adapted to a rural area.

These two churches have a completely different vibe because the architect used different materials that were best adapted to the specific environment of the churches, rural versus urban.

St. Gregory the Great in Portsmith Priory, Rhode Island was the second church Pietro Belluschi built. Unlike the San Francisco cathedral, this church is constructed mostly of natural materials like wood and stone mined from the local area. The building is simple, and the focus is on the limestone altar. Flickr.com/Jim Forest.

Are there any churches that went too far in trying to incorporate ideas of evolution and change?

Absolutely. The thing about experimentation is that some of your experiments aren’t going to work.

Sometimes there were technical reasons for this—when you’re using new materials and building techniques, inevitably there will be some issues because no one knows how everything works. A lot of the new plastics eventually had to be replaced, as did some of the new roof sealants.

Then there are some churches that tried to experiment with liturgical functionality and were never really successful. One example is St. Rita’s outside of Minneapolis-Saint Paul. The building committee had this idea that they were going to have separate spaces for the liturgy of the Word and the liturgy of the Eucharist.

The liturgy of the Word would take place in an auditorium, where films and other events could be held when they weren’t having Mass. Then everyone would get up and move to a separate room where they could stand gathered around a table altar for the Eucharist.

The idea was that the process of getting up and moving would mean everybody would talk to one another. There would be this building of community that would take the parishioners from passive sitting and listening into a more active space where they celebrated the Eucharist as a community. In theory, this doesn’t sound so bad.

But, first of all, the parish ran out of money, so they never built the second space. They just used the auditorium space for a number of years, until they finally decided that it just wasn’t going to work and built a much more standard church space.

And second, just imagine having four little kids and having to herd them from one space to another. I think it would have been a lot more work than they were envisioning. In the end, it was just a space that people didn’t like and that didn’t work for them.

Portsmouth Priory interior. Flickr.com/Jim Forest.

What’s the most fantastic proposed church you came across when researching your book and what does it say about the church as a whole?

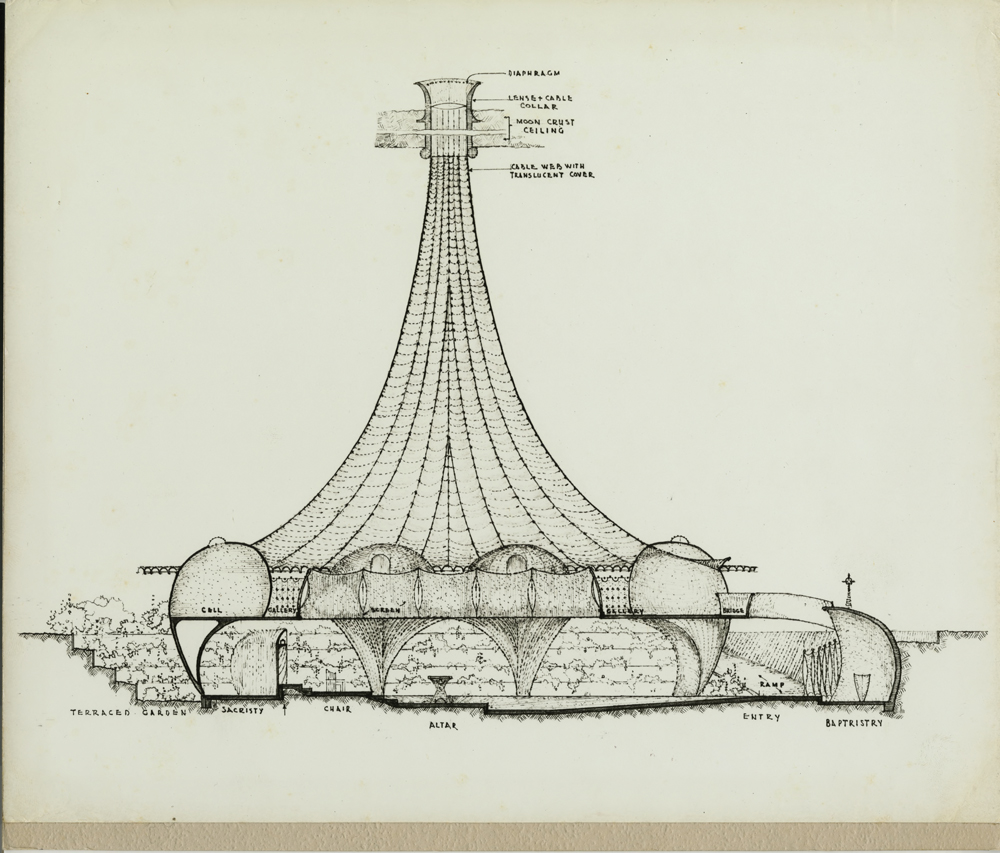

People design churches not only when they have a budget and are actually going to build something but also just to imagine what the future will be like. Like there’s a chapel designed for a permanent moon base, a submarine chapel, and a space station chapel. These chapel designs are intended to get people thinking about what these communities might be like in these incredibly farflung corners of creation, and how they might serve to make Christ present for all.

If technology is going to enable us to go to the moon, go into outer space, or go to the ocean floor, then the church needs to go there too. It’s the Catholic Church’s job to go to the far-off places and, through its liturgy, bring Christ into the world. There’s all this enthusiasm about the first Mass on an airplane and the first Mass in a submarine. Somebody said Mass on the Hindenburg. So when the space program ramps up in the 1960s, naturally people’s thoughts turn to saying Mass on the moon.

The chapel was going to be buried underground—like the entire colony. It’s easier to dig a big hole and put all your climate control down there than to create a giant glass bubble on the surface, which is the other option.

Right over the altar would be a window that let people see outside. If the priest stood at the altar and held up the host, he could look up, see the stars, and have this cosmic connection. The rest of the congregation was going to be enclosed in this translucent tent made out of fabulous new plastic materials that would let people see in and out. There would also be a garden of underground plants that would let them have a connection with the outside world.

That was the other thing about churches during this time: There was this understanding that spaces aren’t entirely sacred or entirely secular. It’s not like God stops caring about people once they leave the church buildings, so these buildings should also reflect the fact that God is everywhere and everything is connected. This was shown in the other two chapels too. The submarine chapel, for example, had glass windows so people could look out on the ocean during Mass.

Courtesy of Mark Mills Papers, Special Collections and Archives, California Polytechnic State University

Can you make any predictions about what comes next in church architecture?

Futurist predictions from the past seem outlandish now that the future has actually happened, but at the time they often seemed like just reasonable predictions. So, with the caveat that I am almost certainly wrong, I think there will be a change in how parishes are used as new immigrant groups continue moving into older churches.

These communities make older churches their own, putting in statues of other saints and changing decorations and colors. I think this has really been the story of the church in the United States: different waves of ethnic groups moving into preexisting spaces and making them their own.

For example, I used to go to St. Joseph of the Holy Family church in Harlem, New York. It’s the sixth-oldest church in New York City; it was built by German immigrant farmers. Over time, the community became primarily African American, and today it’s also increasingly Hispanic.

If you go into that church, you see the underlying German murals that are now overlaid with renovation that uses African wood, statues that were imported from Africa, and paintings of Ugandan martyrs. There’s also a statue of Our Lady of Guadalupe. You can see all the layers of the past and predict that people are going to continue to keep on using the space in a way that is meaningful to them.

This article also appears in the October 2018 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 83, No. 10, pages 32–37).

Top image: Flickr cc via Brandon Doran

Add comment