Bored friends sometimes shoot me emails from their desks at work. They share some trifle that’s going on in their lives, then ask the inevitable question: “What’s up with you? What’s new?” To which I most frequently reply: “Nothing.”

What can be new, I wonder, in the universe of a full-time writer of scripture commentary? The lectionary spins round and round its inevitable cycles. The readings upon which we weigh in do not vary and, as sacred texts, are non-negotiable. One may read voraciously from biblical scholars and other thinkers, always on the lookout for a new angle or a key to unlocking an as-yet-unexplored idea. Is there such a thing? After 2,000 years of commentary on scripture is it reasonable to expect a fresh take on these ancient words?

This is the dilemma both preachers and each faithful member of the assembly face weekly. We’re hoping for a living word that rouses hearts. We live in dread of the same-old, same-old: that tired chestnut rolling around at the bottom of the homiletic barrel, scooped up in those desperate hours when the hour for proclamation arrives before the Holy Muse does. Here we go again: the joke about the priest, the minister, and the rabbi. Or the story about that anniversary trip to Israel. Most of us have a little sympathy for the twice-told tale from the pulpit, since we all have favorite sagas with which we regale spouses or friends—on a too-regular basis, perhaps.

What’s new? What’s changed? Is it possible to have an exciting adventure thrust upon us that might transform us and make us less tedious company for those who love us? Wouldn’t it be great to be able to reply to the next casual “S’up?” text: “I wear a pirate’s patch over one eye now. And I’ve got a very curious scar. But trust me, it was worth it.”

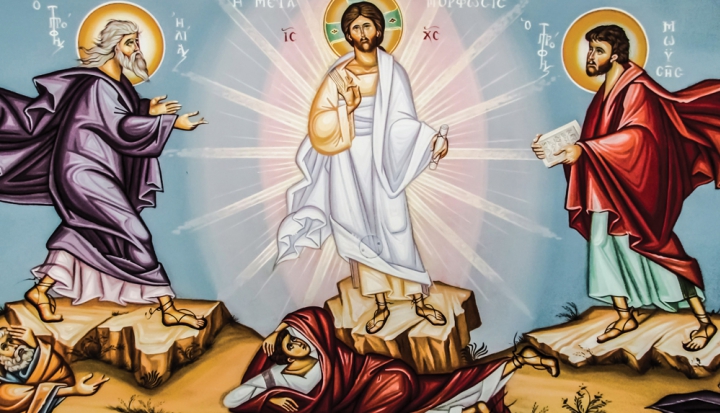

We want, essentially, to have the Jesus-on-the-mountaintop moment. If we’re not to be transfigured personally, we’d like at least to slide down that hill like Peter, James, and John with a whopper of an experience to recount. Diana Macalintal, an expert on liturgical celebration, speaks to this desire in every heart to move beyond the yawn of the ordinary into radical transformation. How sad would it be, she asks, if the bread and wine at Mass changed—and we didn’t?

How sad, indeed, if all the miracle and mystery residing in this sacrament is never communicated to us? Bread and wine become Body and Blood. That’s our faith. Then we partake and become incarnations of Christ, too. But what if we don’t, or at least, don’t know it? Is our Eucharist ever complete if we don’t personally acknowledge how transformed we are and how this sacramental metamorphosis changes everything?

Too often we ask the wrong questions of religion while the right ones are staring us in the face. Macalintal points out that the Eucharistic question we usually arrive at is: “How is God in the bread?” If we stay at this level of theological reflection, we’ll miss the real and urgent inquiry that Eucharist makes of us: “What does it mean for us that God is bread?”

Our liturgy is meant to be that Jesus-on-the-mountaintop moment when Jesus is revealed for us and we are revealed to ourselves. But none of this is to be confused with magic; it’s not something that happens when the official wizard is present and the correct incantation is spoken. Liturgists like Diana speak of a graduated staircase of ascent into liturgical understanding. (Note: There’s no elevator. You have to take the stairs and walk the walk.) The steps that drive us deep into the soul of our liturgy involve recollection, reflection, catechesis, connection, and conversion.

Recollection is what we do normally after an event of any significance in our lives. We tell the story to ourselves or share it with others who were there: What just happened? Recollection can be as simple as talk over coffee in the church hall after Mass as we tell each other what we heard in the homily, what struck us with special force or curiosity during the action of the liturgy, or how a particular hymn moved us.

Next comes reflection, or the savoring of our happening: How did it feel? The Sunday celebration may bring us peace or revive the challenge of faith. Some weeks we’re deeply engaged; at other times, we’re internally distracted. Maybe we find the readings clarifying or more confusing. We feel unity with the assembly one Sunday; we’re isolated and lonely the next. If recollection is about “what happened,” then reflection is about “what happened to me in particular.”

The third step, catechesis, is the long-term exploration of our sacramental event. We seek to understand Eucharist as the church does. We do this through thoughtful attention to what scripture and tradition has to say about it. Faith formation is the formal term for this stage of our inquiry. It can include childhood religion classes as well as adult retreats, seasonal parish missions, and personal spiritual reading, Bible study, or faith-sharing groups. We should have no expectation of outgrowing this stage. We can’t say been-there-done-that about the paschal mystery.

The connection step is simpler—sort of. Connection means linking the fruits of recollection, reflection, and catechesis to our lives. What has our liturgy to do with us? What does it mean for us that God is bread? What does it mean that bread is Christ and we are too? What difference does what we do on Sunday make on Monday? If we keep on doing Eucharist all our lives and can’t answer why, this is a quiet tragedy.

As it is for every other event or relationship in our lives, the bottom line of liturgy is: “So what?” The call to conversion is the great “So What” that our Eucharist demands of us. We perform this action, say these words, and profess this faith: How does all of this make a difference to how we think, feel, behave, and decide?

We return to the original question: How sad would it be if the bread and wine changed—and we didn’t? I’m first to admit I don’t return from the head of the communion line to the pews every week transfigured, with shining face and dazzling clothes. Nor do I return to my routines on Monday with a restored luster to my halo and a cosmically enhanced mercy in every glance. The transformation of liturgy on my life has been more like the lapping of waves on the shore that gradually changes the shoreline completely. You can’t see the influence unless you stick around for a while; say, a lifetime.

Folks who knew me 40 years ago as the girl who never smiled are startled primarily by the presence of joy that friends now describe as standard issue in my character: “What happened to you?” The answer any of us might give is “life, love, and liturgy”—these three being, over time, inseparable for the practicing Catholic. If we’re faithful to the process, the results can be surprising, if not transfiguring. Who knows, you may even get the pirate patch, intriguing scar, and remarkable story to tell. But chances are, you’ll find you no longer need them, on the way to becoming quite a new character yourself.

This article also appears in the August 2017 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 82, No. 8, pages 47–49).

Add comment