No one has asked me, but I am ready with a jim-dandy slogan for promoting good books: Don’t read spiritual books during Lent.

Not only will this slogan put spiritual books into the hands of those perverse people who do immediately what they are advised against. But it has the added value of possibly making the I-read-a-spiritual-book-every-Lent type pause before he boasts.

I can readily think of people who for a variety of reasons—ranging from spiritual pride to scrupulosity—might better read a novel, or a whole series of novels, during the penitential season. But the real point of my slogan is that too often the reading of spiritual books is considered a penance, to be practiced for only a few weeks of the year. Reading one spiritual book a year during Lent is, of course, better than completely ignoring the wealth of spiritual reading available to Catholics—as most Catholics do, I regret to say—but it is a classic case of settling for the minimum when the maximum is so much more satisfying and so easy to achieve.

The greatest deterrent to spiritual reading is that it sounds so dreary—as if it would appeal only to an old woman who makes her own hats and collects Infant of Prague statues. And if the reputation of spiritual reading is not enough to discourage almost everyone who doesn’t know better, the distressingly bad advice palmed off by well-meaning advisers (clerical and lay) on how to select spiritual reading delivers the coup de grâce.

Probably the two most-advised books for beginning spiritual readers are The Imitation of Christ and Introduction to the Devout Life. Most modern laypeople struggle for a while through either or both, then give up the whole idea. Unfortunately, they think something is wrong with the books, when actually the fault lies with the adviser. In general, “spiritual classics” have little to offer the modern layperson. They will bore or confuse, and give people very little they can translate into modern terms. St. Francis De Sales and Thomas à Kempis hold their appeal for scholars and for those advanced in the spiritual life—or so I have been told—but they no longer commute to the modern lay reader. If you are an exception and you find that the Imitation is what you have been looking for all these years—incidentally, the Sheed and Ward edition translated by Monsignor Ronald Knox is by far the best—then treasure it, but be wary of recommending it to others.

The one glorious exception to my out-with-the-old law is, obviously, Holy Scripture. And yet it is surprising how often readers leave the best for last, wasting their time on some book of private revelation by an alleged mystic which they have been told will meet all their unmet needs. There are several publishes that have published biblical commentary meant to illuminate the biblical texts to everyday readers. (Liturgical Press, for example, has a volume titled An Introduction to the New Testament for Catholics that invites non-scholars to discover the richness of the New Testament texts.) Other biblical commentaries examine scripture from a certain perspective, inviting readers to get something new out of the text. Like the Wisdom Commentary, which looks at each book of the Bible from a feminist perspective.

Holy Scripture is the only reading for the soul that is meant for everyone, no matter their vocation, education, or experience. Yet too often it is assumed that every spiritual book ever published should prove helpful and interesting to every reader. But this theory seldom proves true. It is no more true than a similar statement about a pair of shoes. The same book might well prove of value to one reader and boring or even harmful to his friend. Some spiritual books may be designed for different levels of reading or to treat problems that will never concern some people. For any number of reasons, some spiritual books may just not interest you.

The moral to all this: browse before you buy. Select spiritual books which, from a brief preview, would seem to appeal to you and to have something to say to you personally. (This does not mean, of course, that you should avoid books which will activate your brain cells and that you should select pious pap you can read with your mind closed.)

If you do not have a Catholic bookstore or library available in which to browse for spiritual books, read reviews in Catholic magazines or blogs for news of spiritual books that might appeal to you. One warning, however: too often reviewers of spiritual books are too easily pleased or afraid to criticize such a book.

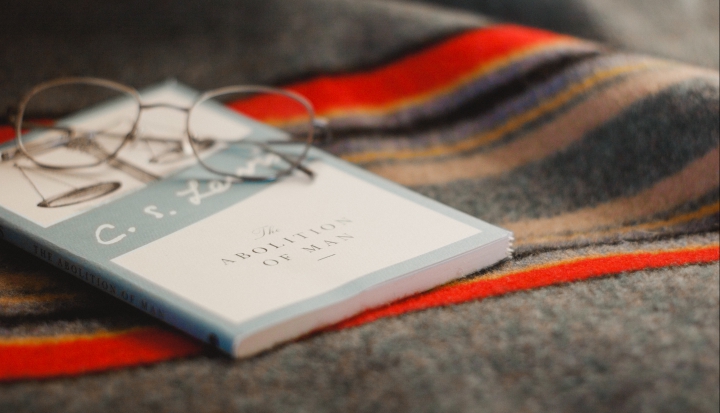

Almost any reader should be able to find enough good reading to last them for many years among the many books of the best of our modern spiritual writers: Thomas Merton, Joyce Rupp, Elizabeth Dreyer, C.S. Lewis, Madeleine L’Engle, and Henri Nouwen are some names that spring immediately to mind, although there are many more. Some write popularly, others more profoundly; all have something worthwhile to offer. Clear style, original thinking, and real insight are characteristic of their works. Their books are available in used books stores, online, and as e-books.

And now a final word about what spiritual reading can and cannot do. Spiritual reading of the right kind can make you better informed, can help you develop your spiritual life, can help ease seemingly impossible burdens, can help you save your soul and help you help others to save theirs. But spiritual reading will not solve all your problems—even your spiritual problems.

You seldom find ready-made answers to your problems in books and no book is a substitute for a spiritual advisor. Not for one minute do I advise an exclusive diet of spiritual reading—most of us can do far better with a balanced reading program. But a Catholic reader who misses the treasures of spiritual reading is missing far more than they realize.

A version of this article was originally published in the March 1963 edition of U.S. Catholic, then called St. Jude. It has been updated to reflect the changing world of Catholic spiritual writing.

Add comment