Liturgy is a river: We come to the same spot many times, yet never enter the same water twice. With the river, it’s because the water’s always in motion; the river of a moment ago is already gone. But in the case of liturgy, even in a year when the language of the ritual is stationary, we ourselves are changed. We may celebrate countless Easters in a lifetime, and still the person we present at each is hardly the same.

The story of the resurrection sounds very different, for example, if you’re celebrating the safe return of a family member from military service, mourning the loss of a dear one to death or divorce, recovering from a serious illness, or recently transplanted to a new location for a fresh start.

If you’ve labored to prepare RCIA candidates and catechumens for the sacraments of initiation all year, the fire of Easter may burn so bright that it honestly outshines the happiness of Christmas. If you lost your job this year and are battling despair, the empty tomb of Easter might seem more like a good place to curl up and hide than one in which to discover hope.

Our priests, too, approach Easter as different people each year. I remember a newly ordained priest who was so excited about presiding at his first Easter Vigil that he brought a camera with him into the sanctuary. After the proclamation of the gospel, he ran around the church snapping pictures of the happy faces in the assembly. “I don’t want any of you to forget the joy of this night!” he declared. He posted the photos in the back of the church for the rest of the season.

I knew another, more elderly priest who chose the occasion of Easter morning to remind us all of the power of Satan and the pains of hell—in excruciating detail. This guy was normally a benign sort of fellow. And I have no doubt that at another time in his priesthood, the meaning of the season appeared differently to him.

There are Easters when I’m ready to belt out “Christ the Lord Is Risen Today” standing on my tiptoes to hit all the high notes. And there was at least one year when I spent the whole Mass crying in an unused choir loft, unable to bring myself to mumble the tiniest responses.

We may attend the celebration with bells in both hands to ring in the return of the Alleluia. And perhaps for some of us there are late April mornings when we wake up in bed and wonder: “Is it still Lent, or have I missed Easter altogether?”

Ready or not, Easter returns each year as faithfully as the Sunday following the full moon after the vernal equinox—technically, the way the date has been calculated since the Council of Nicaea in 325.

You might seriously consider attending the Easter Vigil at sundown on Saturday night, especially if you’ve never done it before, where a selection from nine possible readings and as many as eight psalms await you. Keep in mind: The usual unspoken contract between presider and assembly (you’ll be out in an hour) does not apply on this special night. If the folks in charge know what they’re doing, however, you might not notice or care.

The young camera priest I mentioned earlier decided one Easter to treat the assembly to all 17 Easter scriptures instead of choosing the usual handful. If the Bible is good, more is better, right?

It meant hard work for everyone involved. The lectors were told that the church would be darkened for what our fearless leader was calling “the story hour.” Instead of reading from the lectionary, which we couldn’t do in the dark, we lectors were asked to tell in our own words the passage assigned to us.

The vigil took three hours that year. By the closing hymn, we’d talked and sung our way through the entire story of salvation and baptized and confirmed everyone who stood still long enough. People stayed on for another hour at the reception following, not wanting the beauty and the wonder of that amazing night to end.

The young priest never did that again. And I admit that in another liturgist’s hands, even a 70-minute vigil can seem like a week. Still, among my Easters of happy memory is that long, long liturgy in which 50 lay people and one earnest presider just about died to bring the resurrection to life for others.

There was the year I wound up at a Spanish-language Mass (I don’t speak a word) and stood in the back for two hours with restless children, tired mothers, and men in work clothes just off their shift. We took turns holding the babies and the candles. Without words, we managed to find a common language of faith that enhanced my trust in sign and symbol more than any official sacrament I’ve ever received.

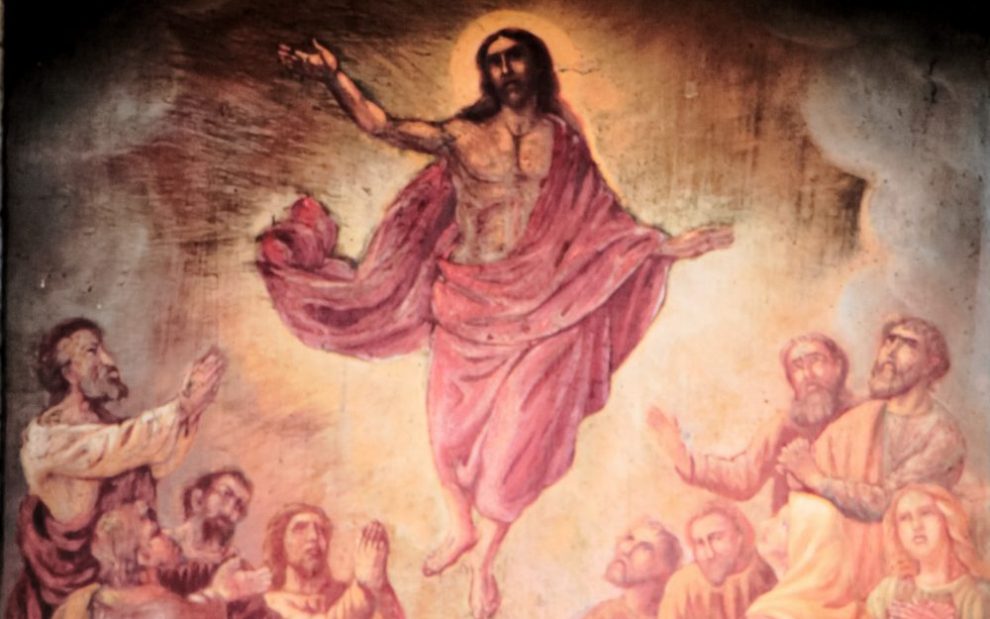

Another great vigil memory is also my earliest: being half-asleep against my older sisters in the first pew of the church. Finally, I was sitting close enough to the action to see what was going on, but was too tired to hold my eyes open. So I dozed between Lucille and Diane, vaguely wrapped in an awareness of singing and candlelight and incense and God lifting up his Son with warm and holy hands to heaven.

Among the best Easters for me, however, was the most recent one. On Good Friday, I was walking home from the Passion service when I ran into one of our small-town “personalities.” This gentleman is nearly seven feet tall with shoes the size of cinder blocks. He dresses with the general fashion sense of Santa Claus year-round and carries a staff the size of a small tree. He also lugs most of his personal belongings with him at any given time.

“Did I miss the Good Friday service?” he asked me. I told him he had, and his face fell. “I’ve been away from God for 40 years,” he said sadly. “This was the Holy Week I wanted to come back.”

“There’s still the Easter Vigil tomorrow night at 8,” I assured him. He was cheered at this. “Wonderful! Can I sit with you?” Everything that just passed through your mind also ran through mine. “Sure,” I said lamely. What were the chances he’d actually show?

He did.

This article appeared in the April 2012 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 77, No. 4, pages 44-46).

Image: Ewald Ehtreiber [CC BY-SA 4.0] via Wikimedia Commons

Add comment