Editors’ note: Sounding Board is one person’s take on a many-sided subject and does not necessarily reflect the opinions of U.S. Catholic, its editors, or the Claretians.

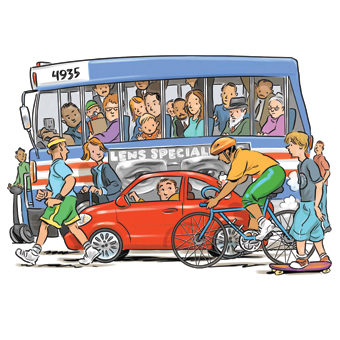

Americans need to curb our enthusiasm for cars before we drive ourselves down the road to ruin.

Time and again, I run into evidence that we Americans just cannot think straight about how and when to drive our cars. I recently overheard two young professionals discussing their daily routine, which included early morning trips to the gym. From what I could gather, each was in the habit of driving his vehicle a distressingly short distance (five blocks? a quarter mile?) to reach the site of his vigorous workout. I could barely contain my burning desire to interrupt with the obvious suggestion: Leave the car where it is and incorporate a brisk round-trip walk or run into your exercise routine. Is there any more contradictory practice than burning gasoline while driving to the gym to get exercise?

Of the myriad ways of getting around in the course of a day, most Americans gravitate disproportionately to the car, even when it makes no sense to rely on one. I keep encountering folks who simply refuse to be dissuaded by the downside of driving from place to place.

Even more, they usually drive alone in vehicles that are generally much larger than the trip requires. We seem constitutionally incapable of calculating the gains and losses of gratuitous car use, or conducting an honest cost-benefit analysis.

Living in a congested area, I often hear boasts from self-proclaimed parking warriors—otherwise gentle souls who take inordinate pleasure in beating the system of parking meters and zone restrictions. Some urbanites giddily portray the quest for 15 feet of unoccupied curb space as the last vestige of the hunter-gatherer society.

But we too seldom ask whether the spoils are worth the cost of the hunt, in time and dollars and mental energy. The hassle of finding parking in crowded urban zones could actually play the constructive role of pushing millions of us onto a bus or train, at least on those occasions when these options are easily available. Sadly Americans have proven impervious to such incentives.

Then there is the sheer financial cost of operating a vehicle. Households that have multiple cars take on a much heavier burden than makes sense, especially given the rising cost of fuel, maintenance, and insurance.

Beyond these obvious costs are the serious harms rendered to the environment, since building and driving more and larger cars leaves a huge carbon and resource footprint. The ecological bill for excessive auto use will eventually come due, especially given the growing aspiration for Western lifestyles in parts of the globe where car ownership was, until recently, quite rare.

I am hardly the first to rail against the indulgent American love affair with the automobile, but repeated calls for change never seem to yield effective reform. An array of cultural forces such as individualism, apathy, and sheer laziness lock our population into counterproductive behaviors. Americans unreflectively insist on maneuvering several thousand pounds of metal, glass, and rubber through the landscape at high speeds to reach destinations that are often within walking or biking distance or on public transportation routes.

So far I have been talking about “them,” laying the blame for irrational behavior at the feet of others. As a Jesuit priest who has never actually owned a car, and as one of the lucky few who lives within an easy walk to my workplace, I can boast of well-below-average reliance on automobiles. But when I reach for an explanation for how Americans came to be so needlessly car-dependent, I think of my personal history and have to admit my own complicity. The car culture affects my psyche as much as anyone’s.

One of the peak thrills of my adolescence was striding up to the counter at the local Department of Motor Vehicles and laying claim to my first unrestricted driver’s license. My burning eagerness to do so (on the very first day of legal eligibility!) is emblematic of how Americans view driving a car as far more than a utilitarian activity, a simple means of getting from point A to point B.

Operating a vehicle evokes overtones of romance, personal freedom, and the validation of one’s maturity. Cruising down an open highway (harder to find nowadays thanks to relentless traffic) is an iconic American experience, one that I admit to indulging in even when alternate means of transportation would have made more sense.

Granted, cars will always have some legitimate role to play. There are places families cannot go without a private vehicle and vital economic functions we could not fulfill without a car. Hauling around children and heavy shopping loads often requires a vehicle, at least on occasion.

I do not mean to make urban life, with its proliferation of transportation options and high population density—both critical in reducing car reliance—the normative situation to the exclusion of all other settings. But I do want to add my voice to those who have long encouraged Americans, wherever they live, to muster up some creative imagination and consider ways they can become less car-dependent.

Besides the millions of individual decisions we make every day about whether to fire up the car or find an alternative mode of transportation, there are pivotal communal decisions made by policymakers who determine the shape of future transportation options. If we have any hope that broader, non-auto options will be available to us in the coming decades, it is to urban planners and public officials that we must turn.

Our hopes for a more responsible future lie in forward-thinking policies such as investing in public transit and high speed rail, and planning denser neighborhoods instead of allowing zoning practices that perpetuate suburban sprawl. The key to better transportation policies depends upon getting the incentives right.

If urban planners and transportation officials follow the path of least resistance and continue to facilitate unnecessary car use, then we will remain locked into this unsustainable relationship with the automobile. But if our policymakers bite the bullet and actively discourage our wasteful reliance on cars by providing cheaper, faster, and more environmentally sustainable options for transportation, then we may find ourselves on a trajectory for real change.

Even prior to considering society-wide planning, appeals to personal discernment and spirituality are especially promising, even crucial. Each of us could benefit from some profound soul-searching about wasteful reliance on cars.

A good old-fashioned examination of conscience might put us in touch with our transgressions and prompt healthier choices. A daily practice of asking hard questions (“How many miles did I drive today? How many of them were unnecessary?”) will likely make us uncomfortable, but it would constitute a modern saintly discipline. The ultimate goal is to forge a set of virtues, to establish laudable habitual behaviors that will lead us to reach for the car keys only when truly necessary.

While a certain level of car usage may be justified, bringing our obligations to God and creation more explicitly into the equation will lead us to loftier standards of stewardship, maybe even a long overdue practice of asceticism regarding transport options.

Members of religious communities with a strong appreciation for God’s gift of the natural world should be in the forefront of the movement to curtail wasteful overreliance on the car. I, for one, ardently hope that there are no Catholics among those driving to their morning workouts at the gym just down the street.

“And the survey says…”

1. I own at least one car.

84% – Agree

12% – Disagree

4% – Other

2. I choose to drive my car because:

65% – It is the only reliable way to get where I need to go.

45% – There is no public transportation available where I live.

29% – I’d rather not walk or bike because it takes too long or can be dangerous.

18% – Sometimes it is just fun to go for a ride.

17% – Public transportation can be too crowded or unreliable.

11% – I don’t drive. I always use other forms of transportation.

7% – I paid for my car and I deserve to be able to use it whenever I want to.

17% – Other

Representative of “other”:

“I mostly walk, bike, or take the bus, but need to use the car for big shopping trips or traveling long distances not covered by public transportation.”

3. Sometimes I choose to drive even when I know there are other equally acceptable means of getting where I need to go.

29% – Agree

66% – Disagree

5% – Other

4. For Catholics, the overuse of cars is a violation of the church’s teaching to care for creation.

54% – Agree

33% – Disagree

13% – Other

Representative of “other”:

“This would be a rather heavy-handed application of Catholic teaching, but we do have an obligation to minimize when reasonably possible.”

5. I’d drive less if there were other transportation options available where I live.

72% – Agree

18% – Disagree

10% – Other

6. Instead of driving, sometimes I:

57% – Walk.

48% – Just stay home.

33% – Carpool with others.

33% – Take public transportation.

29% – Ride my bike.

16% – None of the above. I always drive.

7% – Other

7. It is easy for a priest like Tom Massaro or someone who lives in the city to say we should use our cars less often, but it just isn’t realistic for most suburban families.

63% – Agree

28% – Disagree

9% – Other

This article appeared in the May 2012 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 77, No. 5, page 32-35).

Results are based on responses from 169 uscatholic.org visitors.

Image: Tim Foley

Add comment