In 1980, in the midst of a U.S. funded war the UN Truth Commission called genocidal, the soon-to-be-assassinated Archbishop Óscar Romero promised history that life, not death, would have the last word. “I do not believe in death without resurrection,” he said. “If they kill me, I will be resurrected in the Salvadoran people.”

On each anniversary of his death, the people will march through the streets carrying that promise printed on thousands of banners. Mothers will make pupusas (thick tortillas with beans) at 5 a.m., pack them, and prepare the children for a two-to-four hour ride or walk to the city to remember the gentle man they called Monseñor.

Óscar Romero gave his last homily on March 24. Moments before a sharpshooter felled him, reflecting on scripture, he said, “One must not love oneself so much, as to avoid getting involved in the risks of life that history demands of us, and those that fend off danger will lose their lives.”

The homily, however, that sealed his fate took place the day before when he took the terrifying step of publicly confronting the military.

Romero begged for international intervention. He was alone. The people were alone. In 1980 the war claimed the lives of 3,000 per month, with cadavers clogging the streams, and tortured bodies thrown in garbage dumps and the streets of the capitol weekly.

With one exception, all the Salvadoran bishops turned their backs on him, going so far as to send a secret document to Rome reporting him, accusing him of being “politicized” and of seeking popularity.

Unlike them, Romero had refused to ever attend a government function until the repression of the people was stopped. He kept that promise winning him the enmity of the government and military, and an astonishing love of the poor majority.

Romero was a surprise in history. The poor never expected him to take their side and the elites of church and state felt betrayed. He was a compromise candidate elected to head the bishop’s episcopacy by conservative fellow bishops.

He was predictable, an orthodox, pious bookworm who was known to criticize the progressive liberation theology clergy so aligned with the impoverished farmers seeking land reform. But an event would take place within three weeks of his election that would transform the ascetic and timid Romero.

The new archbishop’s first priest, Rutilio Grande, was ambushed and killed along with two parishioners. Grande was a target because he defended the peasant’s rights to organize farm cooperatives. He said that the dogs of the big landowners ate better food than the campesino children whose fathers worked their fields.

The night Romero drove out of the capitol to Paisnal to view Grande’s body and the old man and 7-year-old who were killed with him marked his change. In a packed country church Romero encountered the silent endurance of peasants who were facing rising terror. Their eyes asked the question only he could answer: Will you stand with us as Rutilio did?

Romero’s “yes” was in deeds. The peasants had asked for a good shepherd and that night they received one.

Romero already understood the church is more than the hierarchy, Rome, theologians or clerics—more than an institution—but that night he experienced the people as church.

“God needs the people themselves,” Romero said, “to save the world . . . The world of the poor teaches us that liberation will arrive only when the poor are not simply on the receiving end of hand-outs from governments or from the churches, but when they themselves are the masters and protagonists of their own struggle for liberation.”

Romero’s great helplessness was that he could not stop the violence. Within the next year some 200 catechists and farmers who watched him walk into that country church were killed.

Over 75,00 Salvadorans would be killed, one million would flee the country, another million left homeless, constantly on the run from the army—and this in a country of only 5.5 million.

All Romero had to offer the people were weekly homilies broadcast throughout the country, his voice assuring them, not that atrocities would cease, but that the church of the poor, themselves, would live on.

“If some day they take away the radio station from us . . . if they don’t let us speak, if they kill all the priests and the bishop too, and you are left a people without priests, each one of you must become God’s microphone, each one of you must become a prophet,” Romero said.

By 1980, amidst overarching violence, Romero wrote to President Jimmy Carter pleading with him to cease sending military aid because, he wrote, “it is being used to repress my people.” The United States sent $1.5 million in aid every day for 12 years. His letter went unheeded. Two months later he would be assassinated.

On March 23 Romero walked into the fire. He openly challenged an army of peasants, whose high command feared and hated his reputation.

Ending a long homily broadcast throughout the country, his voice rose to breaking: “Brothers, you are from the same people; you kill your fellow peasant . . . No soldier is obliged to obey an order that is contrary to the will of God . . . ”

There was thunderous applause; he was inviting the army to mutiny. Then his voice burst, “In the name of God then, in the name of this suffering people I ask you, I beg you, I command you in the name of God: stop the repression.”

Romero’s murder was a savage warning. Even some who attended Romero’s funeral were shot down in front of the cathedral by army sharpshooters on rooftops.

To this day no investigation has revealed Romero’s killers. What endures is Romero’s promise.

Days before his murder he told a reporter, “You can tell the people that if they succeed in killing me, that I forgive and bless those who do it. Hopefully, they will realize they are wasting their time. A bishop will die, but the church of God, which is the people, will never perish.”

The 20th century has been the bloodiest century in history. In what José Martí called the “hour of the furnaces,” Óscar Romero, Nelson Mandela, Desmond Tutu, Martin Luther King, Fannie Lou Hamer, Dom Helder Camara, Maura Clark, Dorothy Kazel, Ita Ford, Jeann Donovan, and Ella Baker accompanied those who were in the sights of the men with guns. They burned brighter.

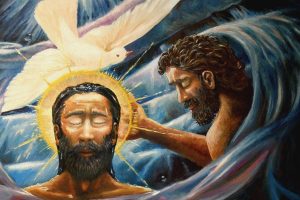

Image: Flickr cc via Eric E Castro

This article is also available in Spanish.

Add comment