A nation with crumbling infrastructure and climate change-induced natural disasters. Civil unrest and violence fueled by a growing gap between the rich and the poor. Wildfires raging through Los Angeles. Rampant, widespread drug addiction. An aged, ineffectual president widely perceived as weak. And then, the election of a charismatic, far-right new president who offers voters a seductive promise: “Make America Great Again.”

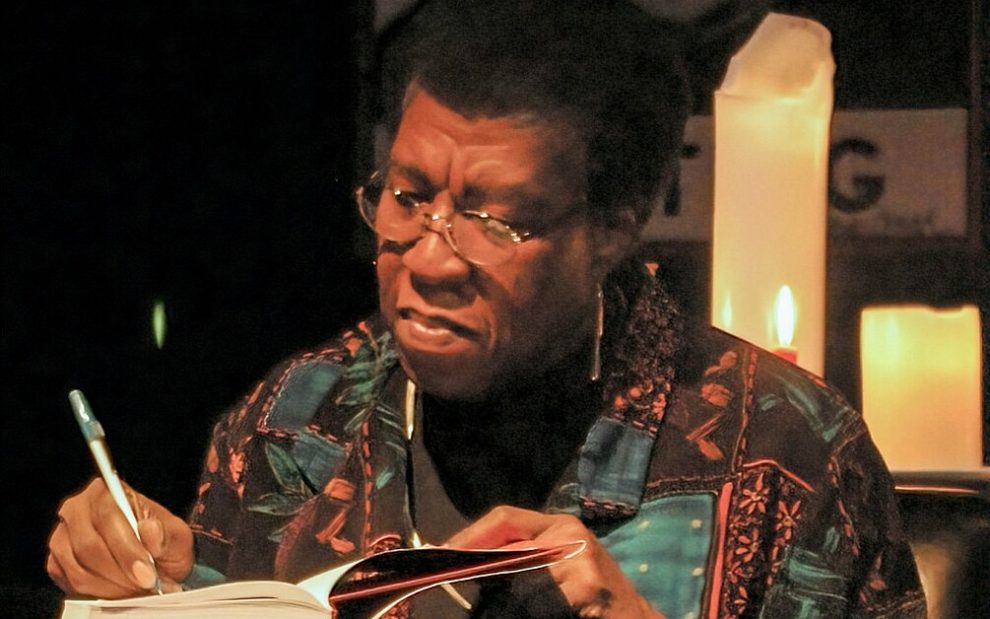

These scenarios, which could be taken from recent headlines, form the backdrop to two novels that acclaimed African American science fiction writer Octavia Butler (1947–2006) wrote in the 20th century’s final decade: Parable of the Sower (Four Walls Eight Windows) in 1993 and Parable of the Talents (Seven Stories Press) in 1998, together known as her Earthseed novels. Many readers have commented about the chilling prescience of the two novels, which take place between 2024 and 2090. But while some would describe them as dystopian, a closer look reveals they are stories of hope.

While Butler was not Christian, she based her tales on Jesus’ parables—which Pope Leo XIV referenced in his first general audience: “The parable of the sower can…make us think of Jesus himself, who, in his death and resurrection, became the seed that fell to the ground and died in order to bear rich fruit.”

Butler’s tales, though bleak, ultimately offer their readers a taste of those riches. Following a teenager’s journey from pastor’s daughter to nationally known leader, the two Earthseed novels affirm the power of human resilience and connection as we strive to bring about a future that offers hope and renewal.

When I returned to these works after Donald Trump’s inauguration, I was reminded of two real-life leaders who offered hope in troubled times and continue to inspire today: Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin, who founded the Catholic Worker Movement on May 1, 1933.

Throughout the two-part story, protagonist Lauren Olamina remains true to her vision of a “God of change” whose will can be shaped by human beings and her belief that we will one day migrate to other planets, ensuring our long-term survival. When faced with persecution and abuse in a rapidly deteriorating United States, Olamina remains true to the vision she calls Earthseed, ultimately establishing a network of small communities of people who share it.

Much like Earthseed, the Catholic Worker Movement began as an inspired vision amid bleakness of the Great Depression. When radical journalist and Catholic convert Dorothy Day met French anarchist and former monk Peter Maurin, their conversations led them to found The Catholic Worker, a radical newspaper still published today.

But, like Butler’s heroine, Day and Maurin found that good ideas were not enough. They soon gathered the marginalized and vulnerable of society in small, autonomous communities with the desire

to create a new society

within the shell of the old

with the philosophy of the new,

which is not a new philosophy

but a very old philosophy,

a philosophy so old

that it looks like new (Peter Maurin, Easy Essays.)

Maurin believed that our modern society was breaking down, that capitalism was at the root of our problems, and that the government would not be coming to save us. He thought that the ultimate destruction of unjust systems would offer an opportunity to build newer, juster systems—like the communities that Lauren Oya Olamina forms. Dorothy Day, like Lauren, became a charismatic leader of the Catholic Worker Movement—a commitment that came at a personal cost comparable to the one Lauren faces as she navigates the tension between caring for her family and remaining true to her beliefs.

There are some important differences between Lauren’s Earthseed communities and the Catholic Worker movement. Most significant is that Earthseed is not Christian. As Lauren matures, she rejects the faith of her childhood and lands on the idea that “God is change”— a concept more akin to tenets of Buddhism or deism ideas than Christianity. While this impersonal view of God offers little personal comfort, the new religion’s adherents find hope in the community and their own agency. In a text she names “The Book of the Living,” Lauren outlines her beliefs in Parable of the Sower in a series of aphorisms reminiscent of Peter Maurin’s style:

Respect God:

Pray working.

Pray learning,

planning,

doing.

Pray creating,

teaching,

reaching.

Pray working.

Pray to focus your thoughts,

still your fears,

strengthen your purpose.

Respect God.

Shape God.

Pray working.

Lauren’s theology is also quite different from our Catholic faith, which, while it emphasizes human responsibility to work for justice and improve the human condition, believes firmly in a loving God incarnated in Jesus Christ.

But while Lauren departs from Christianity, Butler’s views are more nuanced. Both novels end by quoting the parables their titles reference: Luke 8:5–8 and Matthew 25:14–30. Together, these parables embody the vision that Butler sets forth in the two novels: a story of survival followed by rebuilding.

After publishing the novels, Butler stated she saw Jesus’ stories as allegories for human destiny: “We human beings will use our talents—our intelligence, our creativity, our ability to plan, to delay gratification, to work for the benefit of the community and of humanity, rather than for only ourselves. We will use our talents, or we will lose them.”

While Earthseed ultimately becomes a large-scale movement, Catholic Worker has remained grassroots and small. And yet, for nine decades it has continued to community-based alternative visions to those that our individualistic, capitalistic society deems normal. By reminding us that our norms are not “given”—that there are indeed other ways to form relationship and community—Catholic Worker, much like Earthseed, offers a vision of hope.

Right now, as the administration is slashing safety nets, cutting education funding, firing government workers, and forcibly deporting immigrants, people throughout the United States are responding: changing spending habits, giving rides to immigrants in need, donating to humanitarian efforts, protesting, getting involved in politics. These may be small steps, but they are crucial for maintaining hope.

But we also need to imitate Butler in discerning a long-term vision to strive toward. Leo XIV points toward such a vision. In his inaugural Mass, which I was fortunate to attend in person, Leo urged us to “build a church founded on God’s love, a sign of unity, a missionary church that opens its arms to the world, proclaims the word, allows itself to be made ‘restless’ by history, and becomes a leaven of harmony for humanity.”

Leo’s predecessor Pope Francis stood out as someone unafraid to “go to the peripheries” and preach the gospel to all. While Leo’s papacy is very young, he already is reaching out with a similar message. He is bringing hope to many in the United States, who have been frustrated at the failure of political leaders to challenge our current president’s anti-life vision.

As we react to the onslaught of troublesome news, one common refrain is our need to find a positive vision—not just to be against a particular administration’s policies, but to propose clear ideas of what the common good is and then to work toward it, much as Francis did throughout his papacy and as Leo is setting out to do in his first weeks in the Holy See. As we struggle to find hope, visionaries like Butler serve to inspire us.

As a Black woman writer of science fiction, Butler was acutely aware that humans throughout history have endured unimaginable hardships (indeed, slavery makes a brutal comeback in the 21st century as she imagines it). And yet, just as Butler’s ancestors ultimately overcame slavery—and as Butler herself overcame structural racism and sexism to become one of the most successful science fiction writers of her time—the characters in her novels manage not only to survive, but to rebuild and renew.

While Butler may not have been a professed Christian, her novels reach to the heart of the Christian narrative of death and resurrection. I can think of few stories more appropriate for this Jubilee Year of Hope.

At a recent protest against President Trump’s immigration policies, a local community organizer rallied the crowd: “We are the leaders we’ve been waiting for.” This is essentially the message of Butler’s novels. For nine decades, it has also been the message of Catholic Worker. We cannot wait for others to lead the charge. It’s up to us.

Image: Wikimedia Commons/Nikolas Coukouma

Add comment