Both actions are very ancient and began as practical necessities, but eventually the necessities disappeared and were even forgotten.

Later when Christians started to ask what these two gestures meant, they began to interpret the actions symbolically. While these symbols may never have been intended in the beginning, the better ones made sense and became part of our rich tradition.

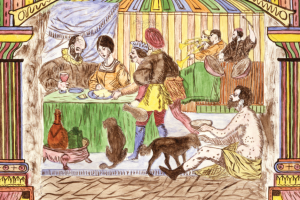

In the ancient world, the Greeks added water to wine because it was often thick, gritty, and too strong. It was simply good taste to add water to wine before drinking it. The Romans loved all things Greek, so they adopted Greek manners and spread them to the lands they conquered. And even though it was not originally a Jewish custom to add water to wine, it soon became part of the Passover meal itself and, hence, part of our Mass.

As early as the fourth century, catechists explained that the water represented humanity and the wine, divinity. Once you put the water into the wine, it’s impossible to take it out again. Because of Jesus, humanity can never again be separated permanently from God. So the custom continues.

The practice of dropping a piece of consecrated bread into the cup may have started because of the ancient Roman custom of the fermentum. Christians in the suburbs could not always travel to Rome for Eucharist. So when the bishop broke the bread before Communion, he would set aside a piece for each missing group. A minister brought this fermentum to each place later, where the priest would drop it into the chalice to be swallowed—and most everyone drank from the cup in those days. Thus the bishop’s Eucharist “fermented” this celebration.

Eventually, the pope also began to set aside a piece for his next celebration. This was called the sacra, and it, too, was added to the chalice to show that this Mass is a continuation of the one before it—the one sacrifice of Christ.

Priests began imitating the pope by breaking off a piece of the bread just consecrated. Some then explained this as a sign of Christ’s resurrection. A body without blood is dead, but when Christ’s body is “reunited” with his blood, Christ is risen. This gesture also continues to this day, being preserved probably because it is so ancient a custom.

This article appeared in the January 2005 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 70, No. 1, page 43).

Image: Flickr cc via Fr. Lawrence Lew, O.P.

Add comment