Yes, the gospels present four different portraits of Jesus. That's the whole point.

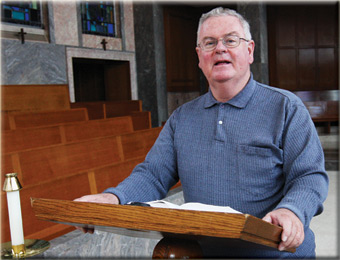

Like many Catholics of their generation, Daniel Harrington's family wasn't made up of Bible readers. Harrington recalls two Protestants coming to his house when he was a child. "We'd like to discuss the Bible," they said, to which his mother replied, "We're Catholics. We don't read the Bible."

Harrington, however, has spent his professional life helping Catholics do just that, not only by teaching scripture for decades but by preaching Sunday after Sunday in the same two parishes for many years. "One of the pastors used to stand at the entrance of the church and tell people they got three college credits for the liturgy," Harrington says of his preaching style.

For Harrington, though, reading the Bible is not just intellectual but spiritual as well. "Immersing oneself in scripture won't necessarily make this or that decision easier for you," he says. "But it does help answer big questions such as: Who am I? What is my goal in life? And how do I get there?"

Harrington admits that Catholics have yet to fully embrace the Bible as their own. "I think religious education perhaps hasn't emphasized the Bible enough," he says. "But the Sunday readings are a great tool for people to learn the Bible. People sometimes don't realize how much Bible they're exposed to."

Harrington sees facilitating that encounter as part of his job. "A preacher has to help people get familiar with the scriptures-and not be afraid of them."

What are the dominant images of Jesus in our culture?

My sense is that it depends on age. I think people 65 and up probably take as their dominant image the Son of God. The middle generation probably takes the Son of Man, because they want to identify with the humanity of Jesus. Younger people? I have no idea what image of Jesus they have. Probably more like a wise teacher or a good example.

In a sense that's not surprising, because each generation in each time and place tends to pick and choose among the many images of Jesus in the New Testament.

I'm always struck, for example, that one of the earliest descriptions of Jesus is as "Lord Jesus Christ." Jesus' death was in the year 30, and the first Pauline letter was around 51, yet Paul uses the title "Lord Jesus Christ" as if everybody already knows of it, as if everybody accepts it.

But the components of that title are enormously significant. To call Jesus "Lord" is to use a word that was used for God and also for the emperor. And to call him "the Christ" means the Messiah, but in Paul's letters it's already functioning as almost a kind of surname. It seems so familiar to the people Paul addresses that he doesn't have to explain it. He simply says, "Lord Jesus Christ."

So the early Christian communities quickly associated Jesus with God?

Yes, as well as using him as a kind of counter-figure to the Roman emperor, which has obvious political dangers associated with it. And as one scholar describes it, the development of belief around the person of Jesus was not a development. It was an explosion.

What story best illustrates Jesus as the Son of God?

The confession of Peter at Caesarea Philippi in Matthew (16:13-20). In Mark, Peter says simply, "You are the Christ." But Matthew adds a qualification: Here Peter says, "You are the Christ, the Son of the living God." That's a step up, and the title Son of God is then woven even more into John's gospel, where Jesus becomes the Word of God and the revelation of God.

I think each gospel in its own way has what we call "high christology," an understanding of Jesus as somehow sharing in God's divinity. Perhaps Jesus' contemporaries saw him as a prophet speaking for God, but the four canonical gospels all portray him as much more than a prophet.

Pope Benedict XVI's book Jesus of Nazareth (Ignatius) makes a very strong point that the gospels present Jesus as not simply a human figure but a divine figure as well. And if you read the gospels with sympathy and not fight against them, I think you have to acknowledge that the pope has made a very important theological point.

If you wanted to focus more on the humanity of Jesus, what stories from the gospels illustrate that?

One would be the temptation stories, where, according to Matthew and Luke, Jesus has to contend with temptations to physical pleasure, fame, a spectacular show, and political power. At each point he rejects these temptations.

These are temptations that every human being is prey to in some form or other. Here Jesus identifies with humanity and shows himself to reflect the best of humanity.

Mark likes to focus on the emotions of Jesus, while the other evangelists tend to omit those references. In the first chapter of the gospel, in the healing of the man with leprosy, Jesus is angry. What he's angry about is unclear-the disease or the power of evil or the power of Satan. He also shows compassion in the same story. So Mark's emphasis on the emotions of Jesus would be an example of Jesus' humanity.

Can you introduce Jesus through the lens of each one of the four gospels?

They all share a common stock of titles: Son of Man, Son of God, Son of David, Lord, Messiah. Those are foundational. But they each take a distinctive approach to the figure of Jesus.

For Matthew Jesus is a teacher, and so he has Jesus giving five great speeches, beginning with the Sermon on the Mount in Chapters 5 through 7. While Mark wants to show that Jesus is a wise teacher and a powerful healer, in that gospel Jesus is also the suffering Messiah.

For Luke Jesus is the great example. In other words he practices what he preaches. This comes up especially in Luke's narrative of the death of Jesus, in which Luke highlights three things that Jesus taught throughout his career: forgiveness of enemies; giving hope to marginal people, such as the so-called good thief; and trust in God, as in Jesus' last words, "Into your hands I commend my spirit" (Luke 23:46).

In John, Jesus is the revealer and the revelation of God. He's the Word of God in the sense that he reveals what's on God's mind, but also he's the revelation of God in the sense that if you want to know what God is like, look to the person of Jesus.

What about Paul? How does he present Jesus?

Paul emphasizes almost entirely Jesus' death and Resurrection and their significance. He's interested in the saving effects of Jesus' paschal mystery. Only a few times does he ever quote a teaching of Jesus. And in one case-the teaching about marriage and divorce-Paul seems to give an exception to Jesus' absolute rejection of divorce.

Paul didn't meet Jesus personally. His experience was with the risen Christ on the road to Damascus. Obviously it was such an overwhelming experience that it changed everything in his life.

What do these specific portraits of Jesus tell us about each writer's community?

Matthew was writing for a predominantly if not exclusively Jewish-Christian community. And the teacher was a very important element in the Judaism of the time; there is great interest in what Jesus teaches. I think what Matthew wants to say is that Jesus is the authoritative interpreter of the Old Testament law, of the Torah. And that he's also the wisest teacher of all, precisely because of who he is-the Son of God.

I would place Mark in Rome around the time of Nero and shortly thereafter. It seems that Mark's community was under a threat of persecution, and they had to come to grips with the mystery of the cross. In this portrayal, Mark hoped they'd find help in the midst of persecution by identifying with the suffering Messiah.

It's hard to place Luke, but what Luke wants to present basically is, as I said, Jesus as the exemplar. Some think, probably correctly, that there are tensions in the community between rich and poor. With stories like the parable of the rich man and Lazarus, with lines like "Blessed are you poor," Luke wants to urge the rich to take a more positive attitude toward the poor and act now before it's too late.

John's gospel is not so much a kind of individual composition as it is a witness to a strand within Christianity, the Johannine strand, which is different from the other gospels. There was a tension, as there is in Matthew's gospel: After the temple is destroyed and the land is even less under Jewish control, how does the heritage of Israel continue? Both Matthew and John try to show that Jesus is the fulfillment of Judaism.

Most important of all for John is that what looks like a defeat-the Crucifixion-is in fact a victory. John deals with the same question that Mark was dealing with: how to explain the death of Jesus. He explains it positively, as part of Jesus' exaltation and not part of his defeat.

Most movie or TV portrayals of Jesus are cobbled together from all four gospels. Is that good or bad?

You lose perspective. By following an individual evangelist, I think you are better able to think the different writers' thoughts and see what they saw.

One way we already do this is with the Sunday lectionary, which leads us through a three-year cycle of readings at Mass. One year we stand beside Matthew, the next year Mark, the year after that Luke, and we hear John from time to time. You can become attuned to the distinctive features each of them brings to the story of Jesus.

I think this is analogous to what goes on in present-day biographies. There are probably hundreds of biographies of Winston Churchill or Martin Luther King Jr. Should we only have one? Or should we have several? Each of these biographies approaches the story of their subject from its own perspective.

Roy Jenkins' biography of Churchill is entirely political. He's not interested in Churchill's alcoholism or his manic depression or whatever. He's interested in Churchill as a political figure, and it's a brilliant book.

In Taylor Branch's three-volume biography of Martin Luther King Jr., Branch focuses on how King figures within American society from the mid-1950s up through his assassination in the late '60s. He covers the place of the black church and other topics. But again, it's one perspective, and there are other perspectives not covered there.

Can we ever get to the "real Jesus"?

If you think you've got the real Jesus here, you're sadly mistaken. History can never give you the real anybody, not the real Ronald Reagan or the real John F. Kennedy or the real whomever. What you get is aspects of the person.

Often people get the impression that some professor somewhere has discovered the real Jesus behind all the details the gospels include. If you look at the books on the quest for the historical Jesus in recent years, however, I think they do tell us something very important. We as Christians believe Jesus was a historical figure. He lived in a certain time and place. He communicated in certain ways. And the more you know about those things the better.

How do you help someone get to know Jesus through scripture?

The spiritual contemplation of St. Ignatius is a good starting point for helping people to develop a personal relationship with Jesus because that method basically gets you into the story. You become a participant, and thus you develop a relationship with Jesus.

This is an exercise of the imagination. Take the multiplication of the loaves and fishes. You situate yourself; you're told, "Sit on the ground and we'll provide food for you." What do you see? What do you hear? What do you smell?

The application of the senses allows you to identify with an onlooker or with one of the disciples, even with one of the disciples who thinks this is all a bad idea. By exercising the imagination, one can insert oneself into the story and thus into a more personal relationship with Jesus.

What if you only had five passages to introduce Jesus to people-your five favorites from across the gospels?

I'd start with the prologue to John's gospel (1:1-18). It provides the New Testament context for the divinity of Jesus and echoes back to Genesis, which also starts, "In the beginning." I think it's a very important text.

The Sermon on the Mount, Matthew 5 through 7, outlines what the disciple of Jesus should strive for and includes the Beatitudes.

Another would be Mark 8, the confession of Peter. That's a great turning point in Mark's gospel, as it is in all the other gospels.

The prodigal son, only in Luke (15:11-32), would be a representative parable because it emphasizes God's mercy and raises the question of what happened to the older son. We never find out whether he decided to change his mind and go to the party, or whether he just ran away.

And obviously the fifth and final would be the Passion narrative. I like all of the death scenes, but especially the hearing of Jesus before the high priest in Mark 14:62. All through Mark's gospel, when people would give Jesus titles such as Messiah or Son of Man, he would say, "No, no, keep this silent." He only publicly accepts the titles of Messiah, Son of God, and Son of Man at his lowest possible moment-that is, when he's been condemned by his own people. The truth is that he can only be understood on the cross.

Are there any rules of thumb to keep in mind when reading the gospels?

I think you have to have some appreciation for the Old Testament as a source for the New Testament. You find references to the Hebrew scriptures throughout the entire New Testament.

Second, these books were written in areas controlled by the Roman empire, which had introduced a certain peace within its boundaries. The Romans got rid of many of the pirates, and they made the roads better. This promoted the spread of the gospel. Travel was relatively easy, so that people like Paul could go from urban center to urban center.

As a result fairly early the gospels begin to circulate around the Mediterranean world. They became unmoored, as it were, from their original historical and community contexts and soon became general information, taken up by a variety of Christian communities.

Third, it helps to know about the cultural assumptions of the Greco-Roman world. Take the importance of honor and shame, for example, which plays a part in the debates between Jesus and the scribes and Pharisees. They pose a question to Jesus and think they've trapped him. He extricates himself from the trap, and thus he comes away with the honor, and they go away with the shame.

The Greco-Roman hierarchical structure featured a few people up top, a lot of people down at the bottom, and some people in between. It's also a patriarchal society in which men are more important than women, where women are supposed to be subordinate to the men.

These are all cultural assumptions, and often they make it difficult for 21st-

century Americans to read the gospels, because what would have seemed perfectly natural to people in the first century to us seems offensive.

In light of these, what do you make of Jesus' encounter with the Syrophoenician woman in Mark (7:24-30), where a foreign woman asks for her child to be healed, and Jesus insults her.

That's a wonderful example because it's the only debate Jesus seems to lose. He wins all the other ones, besting the scribes and the Pharisees and the priests. But this Gentile woman seems to get the better of him.

In the same story in Matthew (15:21-28), she asks Jesus to heal her daughter, and he refuses on the grounds that "I was sent only to the lost sheep of the house of Israel. It is not fair to take the children's food and throw it to the dogs." And she says, "Yet, even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall from their masters' table."

Now you can read that story two ways. One is that this is only a test: Jesus is testing her faith, and she passes the test. Or you can read it in a way that I prefer myself, which is that Jesus gets his horizon widened, and he then ministers to the daughter of this pagan woman. It's interesting that a non-Jewish woman is the only one who gets the better of Jesus.

Matthew's version also presents her as a "Canaanite woman," Canaanites being the enemy of Israel from way back when. He is reinforcing the point that again, this is a non-Jewish woman who seems to get Jesus to do something that at first he did not want to do.

Are there any bad habits that people bring to reading scripture?

One is having an excessive reverence for the text. In other words, reading everything as if it were a factual newspaper account.

Or not understanding the humor in the text. Not getting the joke as with the Syrophoenician woman. Or in Mark 5:1-20, where Jesus casts the evil spirits into pigs. For a first-century Jew that would have been hilarious. The pigs deserved to be destroyed.

Notice that the demons in that story identify themselves as "legion," which of course refers to a Roman legion, the occupying force in the region. That adds to the humor.

Further, by not appreciating the genres of the text and reading everything as if it was the same kind of literary form, people can go astray.

Not every part of the scripture has to be some kind of cosmic statement. Sometimes the text is just talking about runaway slaves, as in Paul's Letter to Philemon. Philemon's slave, Onesimus, runs away, and Paul wants to send him back, but he wants Philemon to accept him as a brother in Christ. It's very practical, not cosmic.

If you could have been present for any of the gospel stories, which one would it be?

The first chapter of Mark's gospel beginning with verse 21. Mark presents it as a typical day in the ministry of Jesus with teaching, healing, and all sorts of interesting things. It takes place in Capernaum, one of the most beautiful places on earth, beside the Sea of Galilee, a beautiful setting, unspoiled still. Every time I visit there I read the first chapter of Mark.

This article appeared in the June 2009 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 74, No. 6, page 18).

Add comment