The modern deacon has been around for 40 years—and some are still finding their place in the parish.

Beverly Hills, California deacon and author Eric Stoltz often finds himself uttering the phrase, "Please don't call me Father."

Besides that gentle correction to well-meaning parishioners, Stoltz also uses the first five minutes of new baptism classes he leads to explain to his captive audience what a permanent deacon like himself does.

It's not just Stoltz's parish that could use more education on the diaconate. As the number of permanent deacons continues to rise across the United States, more Catholics are asking, "What exactly does a deacon do?"

Some Catholics think deacons can hear confessions, anoint the sick, and preside at Mass if a priest is unavailable, acting as kind of a substitute priest-all false. Others wonder why a man would choose to be a permanent deacon rather than a priest. Well, for one thing, a deacon can be married.

But some deacons—about 2 percent—are not married, and Stoltz is one of them. "I've had people tell me, ‘Well, you're not married so why don't you just go all the way?' And I say, ‘Oh, you mean bishop?' " he laughs. "I explain to them that I don't have the vocation to be a priest."

But why be a deacon? Joseph M. Donadieu of the Diocese of Trenton, New Jersey, who was already involved and active in his parish, faced that question. When Msgr. James P. McManimon, who started the permanent diaconate program in Trenton, asked him to consider the ministry, Donadieu asked McManimon what the difference was between an active layperson and a deacon. He received a simple response: "The grace of the sacrament."

Ministry revival

The 2010 figures released by the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA) in May show that the ministry has taken a firm hold in the United States; here deacons account for a projected 17,047, or 46 percent, of the worldwide total of 37,203.

Brooklyn Deacon Greg Kandra, who writes about the diaconate on his Beliefnet.com blog "The Deacon's Bench," says that the reestablishment of the permanent diaconate after 1,200-plus years of inactivity was one of the greatest success stories to emerge from the Second Vatican Council.

"It's a vocation that has just exploded," says Kandra. "The day is fast approaching when the most familiar face in a parish could be a married man with children—the deacon."

While references to deacons can be found in early church records, by the 20th century their role had faded from a full-time ministry to a mere transitional step on the path to the priesthood.

Reviving the permanent diaconate, a ministry in which deacons do not later become priests, was a hot topic at the Second Vatican Council.

"The bishops of the council saw [it] as a way of extending the ministry of the bishop in areas of society that the priests couldn't get to," says Deacon William Ditewig, past executive director of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops' formerly named Secretariat for the Diaconate. The permanent deacon would be an ordained minister working in the everyday world.

In 1968, three years after the close of the council, the American bishops' conference asked the Vatican to approve the restoration of the permanent diaconate in the United States. The first seven U.S. permanent deacons were ordained in 1971.

Beyond the bench

So what exactly does a deacon do? That's a harder question to answer, according to Father Shawn McKnight, executive director of the Secretariat of Clergy, Consecrated Life, and Vocations. He says that scripture and early church texts don't provide particularly concrete descriptions of the diaconate.

"No one can really articulate what only the deacon can do," he says. "He's a servant of charity, but all the baptized are called to be servants of charity."

The Catholic Church teaches that deacons are called to the ministry of Word, liturgy, charity, and justice. In practical terms, it means preaching the gospel, giving homilies, assisting at Mass and liturgical services, baptizing, leading communion and funeral services, and presiding at marriages. It also means joining in charitable, social justice, and community efforts and getting fellow Catholics involved.

To Kandra preaching is central. "I really did feel called to preach and to use my skills in communication and as a writer in a way I never had before." Today he preaches pretty much every week at his parish in Brooklyn.

Canon law stipulates that just like priests, deacons are to preach the Word, but it is often up to the pastor if or how often a deacon gives a homily.

Dung Tran, a Vietnamese American studying for a doctorate in educational leadership at Gonzaga University in Spokane, Washington says, "Just as with priests, there are some really excellent deacon preachers and some who could use a little work." But he adds, "Some deacons' homilies can be richer because they draw from life or family experience."

The Archdiocese of Los Angeles has deacon candidates focusing on a different ministry for each year of formation: service to the sick, elderly, and bereaved; homeless and needy; prisoners; and families. "We've had people fall in love with a particular area of ministry," L.A. formation director Deacon Craig Siegman says. From one deacon's formation experience emerged a successful ministry to homeless people.

"Our most important role [as deacons] is to identify those opportunities where you can gain the participation of parishioners in ministering to the poor and the oppressed," says Stoltz, who has worked in prison ministry and homeless outreach.

The Archdiocese of Seattle requires its deacons to have a ministry outside of their assigned parish. Such outreach beyond one's parish makes a deacon a "spiritual entrepreneur" as McKnight puts it.

Deacon Sam Anzalone, the chairman of the National Association of Diaconate Directors and himself the director in Birmingham, Alabama, sees an emerging understanding of the deacon as a Christian model of service. "We're all called to be servants, but the deacon is particularly singled out as a model," he says.

No weekend warrior

Becoming a permanent deacon isn't as simple as signing up for a few classes, getting ordained, and procuring a parish assignment. While dioceses vary in their formation standards, all are fairly rigorous.

Pentony says his diocese requires each candidate to appear annually before a board to be rated and approved in order to continue formation. "We were constantly reminded that this was a discernment time and no one was guaranteed ordination," he says. But standards and requirements do vary from diocese to diocese.

A wife's consent for her husband to enter diaconal formation is mandatory in some dioceses because of the commitment the ministry requires. A wife is also often encouraged to take part in formation classes. In some dioceses it's mandatory.

Aspiring deacon Wesley Taira and his wife, Lynda, entered the diaconate formation program of the Diocese of Honolulu in January after a year's screening process. The couple joined 20 aspirants and their wives plus two unmarried men for monthly formation weekends that will last five years.

The Tairas say that Wesley has always felt called to ministry. He had taken temporary vows as a Capuchin Franciscan before deciding he wasn't called to the celibate priesthood. Even after marrying Lynda, he continued to hear an ordination call. He even briefly considered becoming an Episcopalian so he could be a married priest.

The idea of the diaconate had come up, but while their two children were young, neither felt it was the right time. Finally in 2008 they attended an informational meeting. "After the meeting Lynda had a thousand and one reasons why we shouldn't do it, all the way [driving] home," Wesley chuckles.

But after multiple interviews as a couple, a psychological screening for Wesley, and further exploration, Lynda was reassured. "I thought, ‘Wow, this is not only for him. It's for us,' " she says.

Particularly appealing was that, for the first time, the Diocese of Honolulu was offering both husband and wife the opportunity to earn a master's degree in theology in a new pilot program. "It's not like this is his thing and I'm here as an attachment, but we're really doing this together," Lynda says.

Nevertheless, the Tairas are already wincing at the sacrifice the program demands. "The hardest part for me is missing out on our own and our children's activities," Lynda says. "We've always been there for everything."

Since all formation is mandatory for both of them in their diocese, they've had to miss their 13-year-old son's Saturday soccer games and taking their 15-year-old daughter to dances.

Then there are the academic requirements. The Tairas both have full-time jobs. Wesley is a counselor and Lynda a first-grade teacher. Now, in addition to work, they're writing papers and reading theology books as they work toward their degrees and his ordination in 2015.

All work, no pay

According to CARA, a deacon spends an average of 23 hours a week in ministry. One in seven spends more than 40 hours a week.

Some pastors expect deacons to put in the same hours as priests. But with 92 percent of deacons married with families, and the majority holding full-time jobs, that's just not possible. And unless a deacon has a salaried church position, he doesn't receive any church compensation. Unlike priests, deacons do not usually accept stipends for funerals, baptisms, weddings, or blessings.

Kandra, of Brooklyn, often encounters time-management challenges. "You want to help people and you want to be of service, and sometimes that's in conflict with all the other things that are happening in your life."

Deacon Michel Pentony of Seattle signed a "ministry agreement" with his pastor, which limits his work to Masses two weekends a month, preaching once a month, and other parish activities. The other person you need an agreement with is your wife, Pentony says, citing two deacons in his diocese who divorced.

Wives also help their husbands keep perspective. Manuela Tugman of Granger, Indiana has to remind her husband, John, that some social or personal engagements are more important than his church-related commitments.

But it's hard to do. Kandra says, "I feel sometimes like the plate spinner on The Ed Sullivan Show, trying to keep all those plates spinning and not letting them fall."

There's no rest, it seems, for even the retired deacon. Pentony retired in July 2010 and moved to a smaller parish in Idaho, where he hopes to have more time for his favorite hobby, fishing. But for now he thinks the fish will have to wait.

"Right now I'm fishing for men," he says. "This is more important than my hobbies."

It might seem that the ideal deacon is the one retired or with grown-up children. Not so, says Ditewig. He has written about the "aging of the diaconate" in his book The Emerging Diaconate: Servant Leaders in a Servant Church.

"The idea that almost none of our deacons are below 40 is stunning and of big concern to me," he says. In the United States permanent deacons can be ordained starting at age 35, with a few exceptions for younger deacons who have permission from a bishop or the pope.

According to CARA, 13 percent of U.S. deacons are retired, up from 7 percent just 10 years ago. That is with the retirement age between 70 and 75, by most diocesan requirements.

That's a huge jump in Ditewig's mind. "Today there's a sense of the diaconate as almost a second career," he says.

Ditewig points to other countries, particularly in Europe, where a quarter of the deacons are under 40. They have a "vision of the diaconate as younger and more deeply engaged in work and family life." To attract the younger candidates, some European dioceses have families attend formation together, offering child care and youth activities.

But in the United States, men are often told to come back when they're older. For Ditewig, this makes no sense. "If this is a vocation from God, we don't normally ask people to put off that call," he says with a tone of slight exasperation. "You'd never tell a potential priest or nun to wait for 20 years."

"We need younger deacons and we need older deacons," Ditewig says. "We need people responding to God's call whenever they hear it."

You are not the father

Father Shawn McKnight calls the assumption that permanent deacons are considered the new substitute for priests "perhaps the most dangerous attitude about the diaconate today." It's an easy supposition to make with the number of U.S. deacons going up and the number of priests dropping.

"You immediately set the diaconate up for a fall if you compare priests to deacons," McKnight warns.

"People still need to be catechized about the diaconate," Kandra says. "They don't understand the difference between being a priest and a deacon."

Along with this confusion often comes a preference on the part of some laity for a priest over a deacon even when both men are doing the same thing.

For instance, Tilmon Brown, a parishioner at the Cathedral Basilica of the Immaculate Conception in Mobile, Alabama has noticed that when a priest and a deacon are distributing the Eucharist side-by-side, the priest's line always seems longer. He attributes that to a "subconscious thought process that receiving communion isn't as holy and blessed if it doesn't come from a priest."

Dung Tran also sees "a priest dependency" in lay Catholics like himself. He remembers going with his girlfriend to the hospital to visit her dying uncle. The family had requested a priest. Instead a deacon came with the Eucharist. That caused a lot of unease. Family members "were concerned or worried about whether he was going to be in a state of grace before he died."

Tran thinks the partiality for priests over deacons is greater among communities of Catholic immigrants who are still getting used to the concept of the diaconate. When a deacon presided over the funeral of his grandfather in Vietnam, "I sensed disappointment from my aunts and uncles," he says.

In order to win over Catholics to his ministry, retired deacon Pentony is careful to involve parishioners as early and as often as he can. "What I try and do is create something new and then lead people into it and have them take it over," he says. He has taught fellow parishioners how to lead the liturgy of the hours and just trained someone to take over the Returning Catholics program he coordinates.

Dealing with the preconceptions of the laity is one thing, but some deacons also have to face "turf issues" with priests. According to McKnight, some pastors harbor "pockets of suspicion and resentment" against deacons.

Eric Stoltz of Beverly Hills says that nearly half the members of his diaconate class ended up switching parishes because of conflicts with priests. He's heard that "it's very common to have pastors not want to have deacons at all, to not share ministry, to not allow the deacon to preach."

At the same time, Stoltz says the pastor at the parish he recently switched to "swears by [deacons] and couldn't get by without them."

Ditewig says, "I think [the attitude] is constantly getting better as priests get used to more deacons and more highly qualified deacons."

"It's always a joy to have deacons," says Father Daren J. Zehnle. The first deacon class for his Diocese of Springfield, Illinois was ordained in 2007, so the church there has "been waiting to see what role the deacon falls into," he says. "Today, where we have a lot of demands, because the culture of our society, for transparency, openness, and in light of the [clergy sex-abuse] scandal, I think the diaconate has a very critical and important role . . . to help the church to be of one mind and one heart."

This article appeared in the December 2010 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 75, No. 12, pages 12-17).

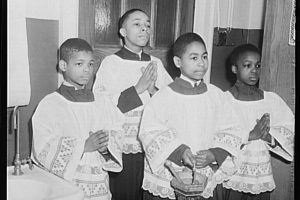

Image: Brothers and deacons Aldolfo and Efrain Lopez pray during Mass at St. Genevieve Parish in Chicago. (Karen Callaway/Catholic New World)

Add comment