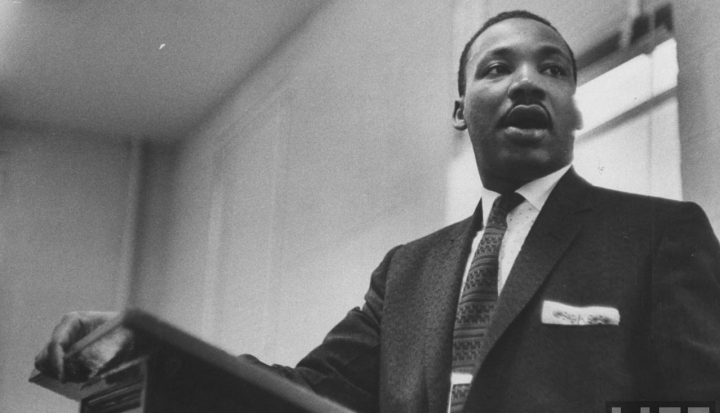

In April we will mark the 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. He was killed in Memphis while supporting sanitation workers on strike who were protesting for a living wage. He died while actively planning for a massive Poor People’s Campaign in Washington, D.C. to dramatize the cruelty of poverty for a complacent nation. He was martyred for his uncompromising advocacy of equal rights for all.

He also died shortly before he was to make an extended retreat at the Trappist monastery at Gethsemani in Kentucky under the direction of spiritual master Thomas Merton. This retreat receives little attention in celebrations of King’s life. But it points to something essential for understanding his importance to Christian believers.

One of the theology courses I teach explores the lives and thoughts of King, Malcolm X, and James Baldwin. My students begin the semester thinking that they already know much about King. They are familiar with his leadership as a civil rights activist; my challenge is to move them to appreciate King as a man of faith. His Christian ideals and religious convictions not only grounded his political strategies but also provided the reservoir of courage needed to endure racial persecution, unrelenting harassment, and the constant threat of death. Without an appreciation of King’s faith, our understanding of the man and the movement that transformed America is both limited and inadequate.

For example, one of King’s spiritual disciplines as a young pastor was carving out significant time each week for prayer and meditation as a part of his sermon preparation. Later in his life, even in the midst of a crushing speaking calendar and the incessant demands of national leadership, King often would spend what he called a “prayer-centered day” in a motel while he traveled, longing for the “spiritual renewal” obtained through inner quiet and contemplative prayer.

King never advocated “pray-it-away” solutions to personal or social problems. He was deeply realistic about the intransigence of evil and how it yields only in the face of determined action and persistent challenge. He knew that prayer alone is insufficient for social change and is too often used as an excuse by Christians to avoid facing difficult social issues.

Yet he insisted that prayer is an essential dimension of social engagement and never a secondary force in the quest of justice. King scholar Lewis Baldwin maintains that King believed that the struggle against the triple evils of racism, poverty, and war required “the combination of prayer, intelligence, and sustained activism.” King’s own prayer life is a witness against opposing spiritual maturity and action on behalf of justice.

One of the most important lessons we can learn from King is how he harmonized his personal piety, intellectual ability, and social vision. Profound faith, piercing intelligence, and compassionate commitment to “the least of our sisters and brothers” informed each other and creating a compelling Christian spirituality.

We need this witness today, because certain currents in Catholic spirituality and seminary formation cultivate forms of prayer and piety that are thinly veiled in their anti-intellectualism and virtually indifferent to a concern for social transformation (with the exception of being anti-abortion). King severely criticized both those who dismissed the relevance of prayer for social action and those who lived what he called a “disembodied Christianity” divorced from an active commitment to racial and economic justice.

In his 2015 pastoral visit to the United States Pope Francis reminded us that America is a great nation “when it fosters a culture which enables people to dream of full rights for all their brothers and sisters, as Martin Luther King sought to do.” King would remind us that only a mature spirituality and deep prayer enabled him to dream and act for justice. He provides a model for the kind of socially engaged holiness that our nation so desperately needs.

Image: LIFE magazine

This article also appears in the March 2018 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 83, No. 3, page 10).

Add comment