On January 21st of this year, the Vatican announced a change to the Roman Missal, per the request of Pope Francis, that women would no longer officially be excluded from the foot washing ritual during Holy Thursday Mass.

A great many Catholics (myself included) responded, “Huh?”

I had no idea women weren’t invited.

I’m turning 40 this year and, as a lifelong Catholic, I can’t remember a Holy Thursday Mass in which women were excluded from the foot washing. Even 30 years ago in my home parish—where girls were still not allowed to serve at the altar—women had their feet washed alongside men. The invitation of a diverse sample of the parish always seemed to me to communicate the rich metaphorical meaning of foot washing: Our priest follows the example of Christ and acts as our servant, not our worldly ruler.

In the Gospel of John, Jesus washes the feet of the 12 apostles during the Last Supper and says:

“Do you know what I have done to you? You call me Teacher and Lord—and you are right, for that is what I am. So if I, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you also ought to wash one another’s feet. For I have set you an example, that you should do as I have done to you. Very truly, I tell you, servants are not greater than their master, nor are messengers greater than the one who sent them. If you know these things, you are blessed if you do them” (John 13:12–16).

Foot washing, like so many of our liturgical rituals, has many layers of significance. Historically, it was a practical ritual for people coming into homes after walking barefoot in the desert. To me, it also connotes ritual cleanliness, baptism, and the necessity of coming clean to the Eucharistic table. And in the washing of one another’s feet, we experience God’s grace.

But most significant, considering the papal decree, is that Holy Thursday Mass (where all this foot washing takes place) is also called the Mass of the Lord’s Supper. It is first and foremost when we celebrate the gift of the Eucharist that Christ gave us at his Last Supper. According to the Roman Missal, it’s also when we remember that Christ gave us the priesthood. Because while the historical Jesus never ordained anyone, we believe that in this act of service to his disciples, he was showing how his own sacrifice should be remembered by his followers.

In the Roman Catholic tradition, theologians have been connecting Jesus’ humble act to priestly service for centuries. Foot washing by priests, according to the Missal, recalls Jesus’ service in the upper room, linking Jesus of scripture to our current understanding of ordained ministry. It also evokes a patriarchy that dates back to the 12 apostles and to the 12 fathers of the 12 tribes of Israel before them.

Because foot washing is associated with an understanding of ordained ministry, some Catholics have insisted that it remains a ritual reserved for priests to perform—one that should take place only in a church and exclude women and non-Catholics as the recipients.

But Pope Francis challenged that interpretation when he celebrated Holy Thursday Mass last year in a detention center and washed and kissed the feet of women, addicts, and a Muslim man. Though many Catholics applauded his actions, others were upset and said that the pope was “breaking the rules.”

So in December of 2015 Pope Francis officially changed the rules when he requested that the head of the Congregation of Divine Worship and Discipline of the Sacraments, Cardinal Robert Sarah, change the instructions in the Roman Missal, the compendium of the official Roman Catholic liturgical practices and prayers. Cardinal Sarah agreed and announced that change in January.

I admit, I first responded to the decree with an eye roll. The exclusion of non-Catholics from a Catholic rite was not all that surprising, but I was miffed to find out that until January 21, 2016, the Roman Missal didn’t explicitly allow for my participation in one of our most beloved rituals, and that priests can opt out of this holy ritual altogether if they don’t want to include women.

In so many parishes, women are routinely underserved and overworked. We’re in charge of everything—RCIA, catechesis, the choir, the bulletin, the food pantry. Sometimes these are paid positions. Often they’re not. Women are the church’s willing servants. Who better to have her feet washed than the woman with five children under the age of 7 who misses most of Mass every week because she’s been asked to run the parish nursery?

Women also tend to anticipate the work that needs to be done and do it long before we’re “officially” asked. I recently interviewed a group of “green nuns” who have worked for decades, often under scrutiny from church officials, on exactly the kinds of care for the earth that Pope Francis called for in his recent encyclical, Laudato Si’. They struck me as representative of so many Catholic women I know who labor unsupported and unacknowledged by the church we love. This seemed like just one more case in which the “official” church came too late to the party, and it stung a little.

Thanks for inviting us; we’re already here. Especially because the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops has officially allowed the foot washing of women since 1987.

It’s true. That’s exactly how the Catholic Church works. It arrives late. It is infuriatingly—and blessedly—slow to change. This is both the price and the reward of belonging to an ancient church. It guards traditions. Sometimes too closely. And sometimes it ignores traditions it would rather not embrace. But Francis’ decree reminds us that it can, and does, and should change.

As Father Antonio Spadaro tweeted in response to the pope’s foot washing decree: “small steps are also taken with feet (and step by step).”

This article appears in the June 2016 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 81, No. 6, pages 34–37).

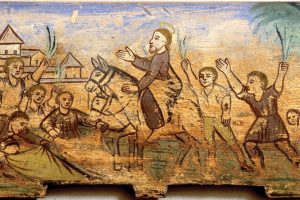

Image: Flickr cc via John Ragai

Add comment