When two friends hang out for 30 years, writing jokes and sketches, trading emails, smoking cigars, and earning Emmys—what happens when one of them comes out as transgender at the age of 61?

The long-term friendship between comedian and actor Will Ferrell and comedy writer Harper Steele began on Ferrell’s first day at Saturday Night Live in 1995. Steele became SNL’s head writer, winning one Emmy out of four nominations, and co-wrote the films The Ladies Man and Eurovision Song Contest: The Story of Fire Saga. Ferrell became famous as a leading man in comedic films such as Anchorman, Elf, and Zoolander, often playing goofy, clueless characters who utterly lack self-awareness (while being wildly hilarious).

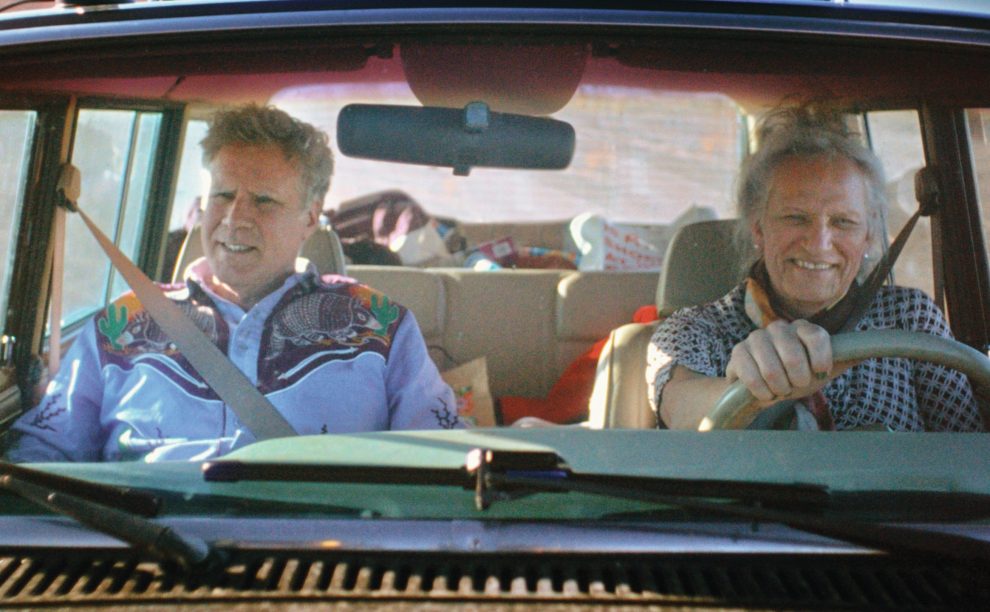

In the Netflix documentary Will and Harper (directed by Josh Greenbaum), the pair climb into Steele’s vintage Jeep Grand Wagoneer in New York and, for the next 17 days, drive toward Los Angeles. Along the way, they talk about Steele’s transition, the very real depression and anguish she felt during the decades leading up to it, and their friendship.

In many interviews, Ferrell admits the conversations in Will and Harper are floundering, bumbling, and without clear resolution—like life. The messiness of those talks doesn’t bother either Ferrell or Steele, who find their way through the tangle while remaining compassionate about each other’s perspective.

What does this mean for their friendship? How is Ferrell supposed to—or going to—react? What happened to his old friend? Is this an entirely new person to get to know?

No one knows what the rules are in these situations, they both say. There’s no wrong thing to talk about, there’s no right way to bring it up; the most loving route is just to start talking. What they also do, but don’t speak directly about, is truly and deeply listen to each other. Steele doesn’t react with defensiveness or outrage when Ferrell wonders out loud about how to talk to her, and we see Ferrell being curious and empathetic about Steele’s experiences, mental health, and physical safety.

These are two very funny people, so sometimes this delicate minefield is negotiated with humor. With Steele behind the wheel, Ferrell cracks, “Do you think you’re a worse driver as a female driver?”

“Ferrell begins to feel something for his old friend now that he didn’t in previous decades: protective concern for her safety.”

Advertisement

Yet carefully, cautiously, and with deep concern for Steele’s comfort and feeling, Ferrell probes. He values the friendship, he wants it in his life, but how that is supposed to work now is unclear to both of them.

The impact of gender on friendship is explored more tentatively than one might wish. They don’t directly grapple with this thorny issue, and more frank dialogues about this would be welcome. Shifting from the ease of a same-sex friendship into some kind of man-woman relationship had to be puzzling. Ferrell claims to have no wisdom about how to navigate this terrain, yet he consistently responds with consummate kindness and compassion. Perhaps that is the path, right there.

It’s a road-trip film, marked by pit stops at quirky sites and shady dive bars. Steele wants to visit places as a woman that, as a fan of long cross-country drives, she previously navigated with comfort. When the friends stop at an Indiana Pacers ball game, they have their photo taken with Governor Eric Holcomb, who recently approved legislation outlawing gender-affirming care for minors. After that awkward meeting, Ferrell and Steele debrief the experience in a revealing conversation about how such policies affect the lives of children and families, as well as trans adults who still feel unsafe.

Steele’s fears—and Ferrell’s—are palpable. They highlight not only hate of trans people but also the cultural and gendered contempt for the feminine. Steele says she can’t discern if she’s afraid to enter a small-town bar hung with Confederate flags because she’s a woman or because she’s trans. It’s an eye-opening moment for both Steele and Ferrell to recognize that men are allowed to move through the world quite differently from women, and that sometimes entering a building as a woman can be read as a transgression.

Ferrell begins to feel something for his old friend now that he didn’t in previous decades: protective concern for her safety. When people misgender Steele, Ferrell gently corrects them. He becomes somewhat courtly and vigilant toward Steele—almost certainly not their dynamic in the SNL writers’ room. When they dine at a steakhouse, and their camera crew and Ferrell’s fame attract attention and hateful social media posts, Ferrell feels guilty for putting Steele in that position.

To have the guy who played Ron Burgundy, anchorman, be the one to teach us how to support trans friends is this film’s fundamental brilliance. Ferrell, known for playing ridiculous characters, is showing us how to behave like a humane human. It’s an example we can follow.

This article also appears in the March 2025 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 90, No. 3, pages 36-37). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Courtesy of Netflix

Add comment