The predominant theme of our contemporary culture is increasingly expressed by a single word: division. From homilies, news, and podcasts to conversations with families and friends, we are bombarded with dire diagnoses regarding divisions in our nation, our churches, our families, our friendships, and our world.

If division is the diagnosis, how, I wondered, could I as an artist and writer use my art as an antidote? Not to push back against the ailment but to offer a different path to new healing possibilities. Sermons are efficacious, podcasts and articles are illuminating, but I felt I could contribute most to the goal of unity by commemorating living witnesses who built bridges instead of walls.

The result was my 52 Catholic Heroes of the 20th Century, a series of icons representing different Catholics of various races, ethnicities, and vocations. Some of them are religious and some laypeople, some are authors and artists, while others are teachers and leaders. Some are popes. Others are children.

While primarily united in their love for and witness to Christ, the secondary element of their lives, connecting them all, is the way they sought to heal divisions, whether political, societal, or religious. These Catholic bridge-builders all worked to find common ground with friends of disparate beliefs.

Here are three of the heroes I highlight—two of whom may not be well known—whose lives expressed this radical commitment to being bridge-builders. Their tools were love and empathy, and their materials were faith and compassion. They offer proof that bridge-building is something we can all achieve with the people we meet every day.

Dame Laurentia McLachlan, O.S.B. (1866–1953)

Margaret McLachlan was born into a Scottish Catholic family and entered the Benedictine Abbey of Stanbrook in 1884, where she took the name Laurentia. Stanbrook Abbey was (and is) one of England’s great centers of learning, and the nuns were custodians of vast archives related to illuminated manuscripts, Gregorian chant, and sacred liturgy.

In the 1920s, Dame Laurentia began to correspond with Sir Sydney Cockerell, director of the Fitzwilliam Museum at Cambridge, and socialist Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw. Both men were atheists, and Shaw was considered an archnemesis of Christianity. Nevertheless, for 25 years, Dame Laurentia, Cockerell, and “Brother Bernard” exchanged fascinating letters on subjects ranging from God and gardening to tango dancing and American boxing. Dame Laurentia never criticized her friends for their unbelief or attempted to convert them. Instead, she allowed her own quiet faith to become a beacon. Toward the end of his life, Shaw began to express the possibility of God’s existence and eternal life after death.

Dame Laurentia, the “enclosed woman with the unenclosed mind,” as Shaw called her, died in 1953. While many of us tend to retreat behind walls when we’re confronted with people whose beliefs challenge our own, Dame Laurentia reached beyond the walls. She met others with friendship and an understanding of the fears, concerns, passions, and happiness that unite us all on our journeys.

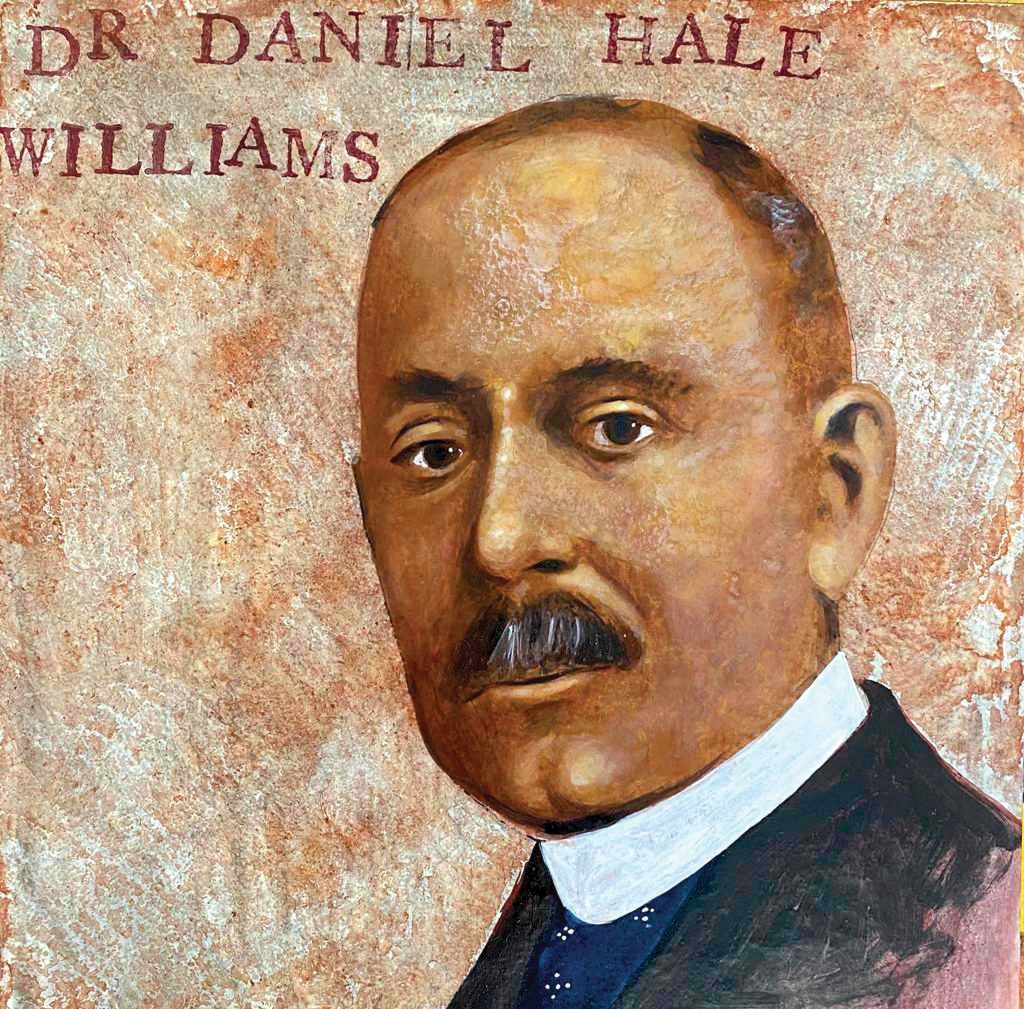

Dr. Daniel Hale Williams (1856–1931)

Apprenticed as a shoemaker when he was 11 years old, young Daniel disliked the work and was drawn to the field of medicine instead. In 1883, he graduated from Chicago Medical College at a time when very few Black physicians were allowed to practice or operate, especially on white patients.

Williams, committed to the cause of justice, had a passion for healing, so he opened his own hospital, Provident, the first Black-run hospital in the United States. The hospital, which accepted patients of all races, was also the first to begin a training program for Black doctors and nurses.

In 1893, Williams made history when he performed the first successful open-heart surgery on a human being. Because of the prejudice against Black people, which included disapproval of surgeons of color, this historic achievement was downplayed and buried for years.

When Williams, a baptized Catholic, died in 1931, he left money to St. Elizabeth’s Church in Chicago. In 1924, St. Elizabeth’s merged with St. Monica’s, the parish founded by the Venerable Father Augustus Tolton.

With people of color still fighting a seemingly interminable battle for equality and acceptance today, Williams saw a path to healing societal wounds by healing people’s physical ones.

Vince Lombardi (1913–1970)

Born in Brooklyn in 1913 to Italian immigrant parents, Vincent Thomas Lombardi planned to become a priest. He enrolled in a preparatory seminary but, eventually, he found his vocation as a football coach. After a succession of coaching jobs at various universities, Lombardi became head coach of the Green Bay Packers in 1959. He transformed one of the worst teams in the NFL into one of the greatest teams with the most wins in league history.

Lombardi’s philosophy, not only on the field but in life, was rooted in his faith, his devotion to the sacraments, and his practice of attending daily Mass even when he was on the road. His faith was not a private dialogue with God but manifested in his fight for social justice in a hostile culture.

While segregation was still enforced throughout the NFL, Lombardi denounced it and refused to play any team that enforced it. Due to his insistence and support, former player Bobby Mitchell rose to an executive position with the Washington Redskins, becoming the first Black executive in the NFL.

Lombardi’s brother Harold was gay, and Lombardi became an early and brave advocate for the LGBTQ+ community. He welcomed a gay player on his team and would not tolerate homophobia on the field or in the locker room. He was not interested, he said, in a person’s sexual orientation but in the talents and abilities that reflected their deeper character.

In 1970, Lombardi was diagnosed with a fast-moving cancer that took his life on September 3 of that year. On his deathbed, Lombardi told a priest he was not afraid to die but only regretted he had not accomplished more.

History tends to pigeonhole Lombardi according to winning seasons and snappy aphorisms, but Lombardi’s enduring legacy lies in his ability to see beyond race, sexuality, and religion to the human being within, and his determination to push people to be their personal best, both on the field and in their lives.

These heroic Catholic bridge-builders remind me that my primary goal should not be monetary success or fame. Instead, I am called to work that teaches others about God and the paschal mystery. For me, a deeper understanding of the communion of saints is a good start.

Our work—whether art or sports, business or medicine—must resonate with the good, true, and beautiful and with people of all beliefs. Our efforts can be signposts on their journey. We see this in widely known heroes such as Mother Teresa, Pope John XXIII, Dorothy Day, and Thomas Merton, but it is exciting to also discover hidden jewels such as John Ford, Caryll Houselander, Bernhard Lichtenberg, and Dorothy Stang.

The trajectory is obvious. If the light of Christ can radiate from the sacrifice, service, and bridge-building in lives both well-known and hidden, my life, my work, and my own service can bring light to the people I meet every day.

This article also appears in the January 2025 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 90, No. 1, pages 17-19). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

All images by Joseph Malham

Add comment