It did not come as a total surprise when Pope Francis, while visiting the United States in 2015, invoked the name of Dorothy Day. From the beginning of his papacy, it had almost seemed that he was channeling her spirit. More remarkable was the context—in an address before a joint session of Congress, and among a group of “four great Americans” (including Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King Jr., and Thomas Merton) around whom he organized his remarks. “In these times when social concerns are so important,” he stated, “I cannot fail to mention the Servant of God Dorothy Day, who founded the Catholic Worker movement. Her social activism, her passion for justice and for the cause of the oppressed, were inspired by the gospel, her faith, and the example of the saints.”

It is likely that few members of Congress recognized her name. Among those who did, some might remember that she had been called many less flattering names than “great American.” Yet, how could Pope Francis fail to recognize in Dorothy Day a kindred spirit? In Evangelii Gaudium (The Joy of the Gospel),he had written in terms that might have appeared in The Catholic Worker: “Just as the commandment ‘Thou shalt not kill’ sets a clear limit in order to safeguard the value of human life, today we also have to say ‘thou shalt not’ to an economy of exclusion and inequality. Such an economy kills.” In words that Day might have written, he observed: “How can it be that it is not a news item when an elderly homeless person dies of exposure, but it is news when the stock market loses two points?”

In his first trip outside of Italy, the Pope visited the island of Lampedusa, a way station for immigrants, thousands of whom have drowned at sea. There he decried a “culture of comfort” and the “globalization of indifference” that renders us incapable of feeling the pain of others. Who weeps for these victims, he asked? Clearly Pope Francis does, as did Dorothy Day before him.

Before the Pope’s trip to America, I had imagined the pleasure of telling him about this American Catholic who had so embraced his vision of a church that is “poor and for the poor,” whose call for a “revolution of the heart” was echoed by his own call for a “revolution of tenderness.” I would have described how she “touched the wounds of Christ” every day; how she spoke out and demonstrated against war and injustice, going to jail in solidarity with striking farmworkers or protesting plans for nuclear war; how she stood virtually alone among Catholics of her day in bearing witness to the gospel message of nonviolence, the commandment to love our enemies. In light of the Pope’s great encyclical on ecology, I would have pointed out the farming communes she established and her reverence for creation.

I would have described her spirituality, inspired so much by the “Little Way” of St. Therese of Lisieux; her conviction that all our small acts of faithfulness and love can help transform the world in ways we may never see. I would have told the Pope how Day exemplified the Beatitudes; that hers is the face that comes to mind when I envision the poor in spirit, the meek, the pure of heart, the mournful, the peacemakers, and those who hunger and thirst for God’s righteousness.

But evidently no intervention on my part was necessary. Pope Francis was apparently well briefed about Dorothy Day before undertaking his trip. His references to Day, Merton, Lincoln, and King were only part of a remarkable speech in which he expressed his solidarity with immigrants (the subject of so much vilification in this political season); called for abolition of the death penalty; affirmed that the common good also includes the Earth; denounced the “blood-drenched” arms trade; and defined what it means to make America “great” (before this became a slogan laden with very different connotations) in terms of the dreams embodied by his four great Americans.

But what, on the other hand, if I could have sat down with Dorothy Day to tell her about Pope Francis? How thrilled she would have been to learn of a pope who took his name from St. Francis. So often she criticized the ecclesial trappings of power and privilege. How she would have delighted in Francis’s gestures of humility, his call for shepherds “who have the smell of the sheep,” his washing the feet of prisoners (including women and Muslims!). With her lifetime among the poor and discarded, how she would have resonated with his words: “I prefer a church which is bruised, hurting, and dirty because it has been out on the streets, rather than a church which is unhealthy from being confined and from clinging to its own security.” How moved she would be to learn of his deep friendship with a Jewish rabbi, his love for opera and Dostoevsky, and his exhortation to spread the “joy of the gospel.”

But there is another, personal level on which Day would connect with a Pope who could describe himself simply as “a sinner whom the Lord has looked upon.” Her early life was marked by her passion for social justice but also by much sadness and moral confusion. In her early life, following an unhappy love affair, she had an abortion and twice tried to commit suicide. As she later wrote in her diary, “Aside from drug addiction, I committed all the sins young people commit today.” It was later, while living on Staten Island with a man she deeply loved that she again found herself pregnant, an experience that struck her this time as a sign of God’s mercy and grace. In joy and gratitude she decided to become a Catholic. It was a choice marked by great sacrifice—separation from the father of her child, the love of her life, who refused to have anything to do with marriage. Looking back on all of this, she could observe: “God has been so good to me.” In the end she had found a way to combine her faith with her commitment to the poor and oppressed. For Day, gratitude was the final word—for the life and faith she had been given and for the vocation she had found.

She would have appreciated Pope Francis’s words: “I have a dogmatic certainty: God is in every person’s life. . .Even if the life of a person has been a disaster. . .God is in this person’s life. . . Although the life of a person is a land full of thorns and weeds, there is always a space in which the good seed can grow. You have to trust God.” That was Dorothy’s experience. It was God’s mercy that drew her to the church. How could she not love a pope who has made mercy the signature theme of his papacy?

In invoking Dorothy Day and his other models, Pope Francis said such men and women “offer us a way of seeing and interpreting reality.” In the context of Dorothy Day’s proposed canonization—a cause that is currently in process—perhaps Pope Francis’s words help us understand what this means.

We are accustomed to thinking of saints as people who stand out for their heroic faith and witness to gospel values. But before their bold and courageous actions, perhaps what distinguishes such people is their way of seeing and interpreting reality. They look at the world through a gospel lens—and in doing so they see things according to a new scale of value. What would it mean if we saw in the poor and homeless, as Dorothy Day did, the face of Christ? We might not immediately open our homes, as she did at the Catholic Worker. But perhaps we would not be so susceptible to what Pope Francis calls “the culture of indifference.”

I think that among the many things Pope Francis and Day share in common is their recognition of the value of small gestures and poor means. One of the Pope’s favorite mottos is this: “Time is greater than space.” As he explains, “This principle enables us to work slowly but surely, without being obsessed with immediate results. . .Giving priority to time means being concerned about initiating processes rather than possessing spaces. Time governs spaces, illuminates them and make them links in a constantly expanding chain with no possibility of return.”

Compare that to Day’s words: “What we do is very little. But it is like the little boy with a few loaves and fishes. Christ took that little and increased it. He will do the rest. What we do is so little we may seem to be constantly failing. But so did he fail. He met with apparent failure on the cross. But unless the seed fall into the Earth and die, there is no harvest. And why must we see results? Our work is to sow. Another generation will be reaping the harvest.”

This of course has much bearing on the Pope’s strategy for change, both in the church and in the world. Many people focus on seizing power, occupying space—but for the Pope the key thing is planting seeds, initiating processes. The revolution of the heart, the revolution of tenderness, does not depend on seizing power, or occupying space. But it initiates a process of change that may in the end prove more durable. That is the basis of his vision of synodality. As Pope Francis writes, “We can know quite well that our lives will be fruitful, without claiming to know how, or where, or when. We may be sure that none of our acts of love will be lost, nor any of our acts of sincere concern for others. No single act of love for God will be lost, no generous effort is meaningless, no painful endurance is wasted. All of these encircle our world like a vital force.”

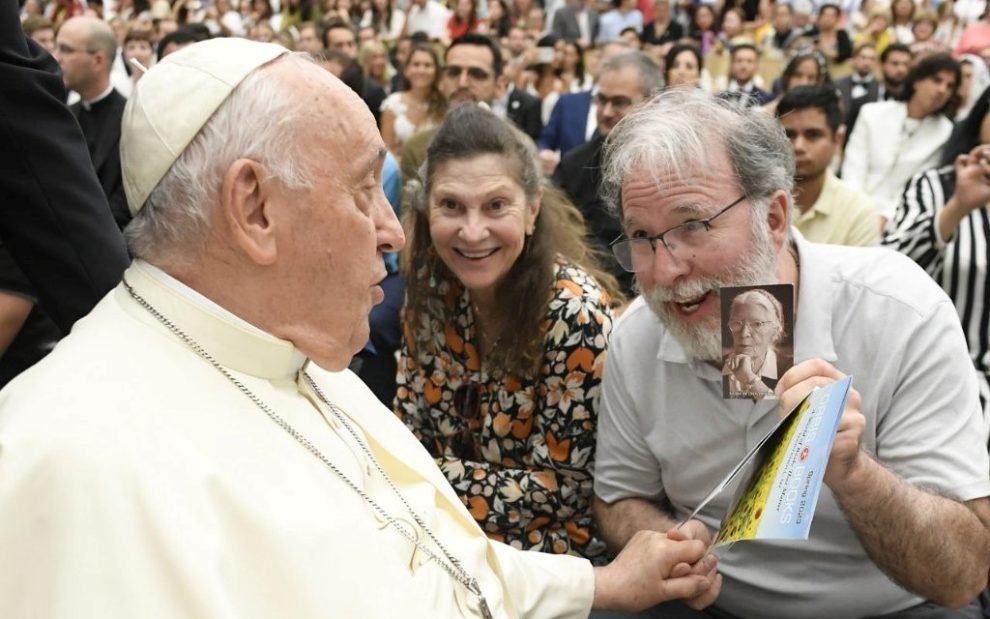

Last year, in a brief audience with Pope Francis, I faced the challenge of summarizing all of this in a single sentence. The occasion was the publication by the Vatican of a new edition of Day’s memoir, From Union Square to Rome, for which the pope had supplied a foreword. Placing one of the first copies in Pope Francis’s hands, I simply told him that I had worked with Dorothy Day, and added, “You are the shepherd of her dreams.” Smiling in recognition of the holy card I was holding, he said only two words: “Dorothy Day!”

Image: Robert Ellsberg gives Pope Francis a book by Dorothy Day, courtesy of Robert Ellsberg

Add comment