Cassidy Hall learned something important about contemplation from her toddler-aged nephew. “I picked him up from preschool one day, and I pointed to a Santa Monica statue,” she says. “I said, ‘Look, that’s Santa Monica, who our city is named after.’ And without missing a beat, he says, ‘No, that’s God. God is a girl. Don’t you know that?’ A few weeks later, we passed the same statue and I pointed it out again and he says, ‘No, that’s Buddha.’ I just loved this moment and how it opened me up to ways of thinking like a child, something so crucial and important for the spiritual life. My nephew could look at something that is literally made of stone and say that it was something else. And that has given me permission, in some way, to see the things in myself that I once thought were stone and allow them to change and expand.”

Hall is an author, filmmaker, podcaster, and ordained minister in the United Church of Christ. She is also the author of a new book, Queering Contemplation: Finding Queerness in the Roots and Future of Contemplative Spirituality (Broadleaf). For her, this story about her nephew’s expansive perspective into faith and spirituality illustrates what contemplation is all about.

“Both contemplative life and queer bodies live in this kind of liminal space,” she says. “There’s a depth of connection to our own becoming, our own expansiveness.” In her book, she explores how queerness and contemplation overlap and envisions how applying a queer perspective to contemplative prayer can enrich spirituality.

What is contemplation?

One of the beauties of contemplation is that it is different for everyone. It’s those intentional pauses or moments that all of us can take no matter how busy, loud, or difficult our days are. Contemplation allows us to discern and understand who we are and what we are meant to act toward. I always think of writer and spiritual director Therese Taylor-Stinson’s words about what contemplation is; she says that contemplation’s wholeness relies on inward solitude and reflection, and it is also an outward response to what we find ourselves present and awake to.

I think many traditional definitions of contemplation lean heavily on inaction and going away from the world to love it more deeply. Many times, Christian contemplation has been used as a hiding place. But contemplation was never meant to be a hiding place where we can avoid doing or acting or being in the world. Contemplation is action, and lasting action often includes contemplation; they need to coexist.

When we think of contemplation, we often think of thinkers such as Richard Rohr, Thomas Merton, Cynthia Bourgeault, Howard Thurman, Evelyn Underhill, and Martin Laird. In fact, many times we first think—or only think of cisgender, straight, white men. Overall, contemplation and contemplative writing are missing out on a lot of voices, especially voices from the margins whose experiences are unlike the status quo, including the voices of Black women and other people of color. We don’t often hear from the queer community or LGBTQ+ folks. We’re really missing out on hearing from any marginalized or oppressed community. I tried to remedy this a little in my book, but I still come from a very privileged position. I’m still a white woman in America. I’m queer, but I grew up in a home that was supportive and welcomed me; my coming out wasn’t really a coming out, it was just existing. It was really important for me to include at the end of every chapter another position, another viewpoint, another way of looking at contemplation.

Is contemplation accessible to everyone or is it a privilege reserved for a few?

When we think about contemplation as a formality, as groups and practices, silent retreats at monasteries, then yes, contemplation is a privilege. Very few people will have total access to it, whether because they have children, because of where they are located, because of financial pressures, or whatever.

But contemplation should be accessible to everyone, no matter who they are or what resources they have. It’s not about going on an expensive retreat or spending days away from work praying; I experience contemplation when I do something as simple as look at the tree outside my window for a few minutes.

One of my greatest hopes for my book is that it points to the ways in which contemplative life is accessible and within reach for everyone. I want to acknowledge that contemplative life is in these tiny beats throughout our day. Everyone in my life is already doing contemplation. They might not call it contemplation or silent prayer or solitude, but they are doing it in some small way.

Maybe it’s looking at the tree outside their window or having a moment of awe with their child looking at a butterfly. Maybe it’s talking to their plants or their cat. Sometimes it’s that sacred pause we make when we’re reading a book and something clicks in our head and we stop for a second. Those moments aren’t just accessible, they’re already happening.

I think it’s the language and the ways in which we formalize contemplation that make it inaccessible. When I started practicing contemplation, I didn’t even know how to pronounce the word. And sure, a silent retreat or getting away for centering prayer is nice, but that’s just not how the world works. We don’t all have access to that.

What does it mean to “queer contemplation”?

The way I define queer in the book is not just related to my sexuality: It is the way I tilt my head to look at the world. I think contemplation and contemplative life invite us to do the same thing—to tilt our heads to look at the world. To look curiously, differently, more openly, and more expansively.

One of the beautiful things about queerness and contemplation is that both permeate the world with that weirdness, oddity, and strangeness and allow it to flourish as it is, whatever that means for our own lives. So when we queer contemplation, we give it this expansive permission and, in turn, give ourselves permission to grow and evolve toward wholeness.

You write about monasticism as being fundamentally queer. What do you mean by that?

Monasticism is weird and odd and strange, and it is also incredibly beautiful and challenging. Monastic life challenges me to be more involved in my community—the way they do communal living, how they do daily prayer seven times a day, the way they stick to these routines and rituals in everyday life and make vows of things like stability.

What’s queer about monastic life is that it is so different from most other life experiences. It has really shown me that when I choose to be committed to something—whether a practice, a person, or even a place—it opens me up to a level of connectivity and union I could not otherwise reach.

Clinical psychologist and former Trappist monk Jim Finley speaks to this as it relates to relationships with another person. He talks about “oceanic oneness,” saying, “Two lovers cannot make moments of oceanic oneness happen, but together they can assume the inner stance that allows them to be overtaken by the oceanic oneness that blesses their life.” That inner stance, that commitment, is something I really revere and respect about monastic life because it opens us up to something.

In addition, spiritual life lives in paradox. Monks go away from the world—stick to these routines, live in this enclosed space—to love more deeply and open them up to something that can’t otherwise be touched or experienced. That’s a paradox. And that’s exactly where I believe spiritual life flourishes and can actually grow.

If you look at your spiritual life through this queerness, this tilted head, how does that affect your relationship with the divine?

It’s made me so much more alive and free, so much more liberated, playful, and real. I think tilting my head to look at the world has reminded me to tilt my head when I look at God or the divine. It’s really awakened me to seeing my spiritual life everywhere.

In respecting and revering my own evolution, I in turn try to do that with everyone around me. And that also gives God permission to become and evolve and change. I have had various periods of spirituality in my life that I’m not very proud of, and it’s just been such a gift to free God and free myself. That’s where the Spirit lives—in that freedom and dance and play.

You write that silence—which people think of as the foundation of contemplation isn’t always healthy or good. Can you talk a little about how to know when silence is hurtful instead of life-giving?

Toxic silence can show up when we give one another the silent treatment; it is oppressive, dominative, and minimizes other people’s experiences. In the book, I give an example of being in a relationship that was kind of secretive—I was with someone who wasn’t out—and how this did harm to who I was and how I am in the world. That was a kind of toxic silence.

I think we subconsciously engage in these types of toxic silences more often than we like to admit, whether it’s giving someone the silent treatment or just not speaking up when we see something wrong because it’s easier. Loving silence, on the other hand, is akin to basking in the unknown and in the ways that contemplation leads me to listen most closely to myself.

How do we make sure we are fostering this life-giving silence while also making sure we aren’t fostering an environment where toxic silence can take root?

It’s true that all too often silence has been used as a hiding place. But if we’re really engaging silence in a truthful and honest way, we know what we are to engage with or speak or do in the world. There are all sorts of contemplative groups in the world that are focused on meeting for prayer, but how many of these groups also meet to act in the world? I don’t know—hopefully some. But I think that when we engage silence truthfully and from an authentic place, then it leads us to know how to act to make the world better.

There are some people who may, for whatever reason, feel unsafe or unwelcomed in many religious communities. How can these people start to reclaim a contemplative prayer practice?

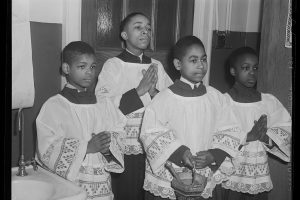

I think that reclaiming contemplative life in a way that leads people to find safety in it actually goes back to the roots of contemplation and to the desert parents (my nongendered term for the early Christians we often call the desert fathers and mothers). These folks were weird, and beautifully so. They created these communities of care and love.

Today, some queer communities are doing something similar. They create these communities of liberation and love and deep care for one another. There’s a queer yoga group in my community and a queer coffee group, and all these communities that are emerging are spaces of sacred pauses, of reflection, of connection. And the desert Christians of the third and fourth centuries modeled something similar for us. I think the world in which we live took us away from those kinds of communities.

These types of safe communities are within reach, but unfortunately they don’t exist in many religious communities. I think it’s so important to cultivate community where we’re really looking out for each other; this is the true origin of contemplative communities.

And I think it’s actually the world we live in that took us away from that. The safety isn’t always within reach in religious communities. And it can feel rare when we do find it.

What does a queer faith practice look like?

A queer faith practice is one that is true to exactly who you are. It’s important to remember that we are ever-changing. That ever-growing is a crucial aspect to what a queer faith practice is, because it gives us permission to keep blooming and keep changing.

What does contemplation look like in your own life right now?

It takes shape in a lot of ways. Sometimes it’s the daily experience of checking in on my plants and talking to them a little bit. Yesterday I took all my plants outside for sunbathing. On Mondays, it looks like going to Zen meditation. Sometimes it’s going on a walk and listening to the birds and trying to parse out the different bird songs, which has been a really fun practice lately. And sometimes it’s just pausing to look out the window. It’s all these beats and moments of intentional stopping.

What’s crucial is that all these moments allow me to discern and move me toward both who I am as my true self—which also means what I’m to speak to and how I’m to show up in the world. So maybe that moves me to go to the Indiana State House to protest the most recent anti-trans bill. Maybe it means going to volunteer at Habitat for Humanity. Or maybe it means writing a letter to a friend or making sure I’m in touch with my community in some way. But, for me, contemplation is always tethered to action.

In your book, you write that while Thomas Merton led you into the contemplative life in some ways, there was this moment where you “broke up” with him. What led to this?

It’s so important to be able to look at the ignorance of someone like Thomas Merton alongside his wisdom and acknowledge the presence of both. I think it’s also important to ask ourselves if we can navigate the tension, the cognitive dissonance.

I came to Merton’s work while I was working as a substance abuse counselor in Iowa. The work was great, but it was also hard. I started Merton’s New Seeds of Contemplation in between client appointments, just trying to figure out my life, what I wanted, and why I was here. Ultimately, that led to me looking up Trappist monasteries online. I saw that Gethsemani was a 12-hour drive from where I was living, so I took a long weekend to visit and had my own little silent retreat. I fell in love with the place. But then I went back to life and my work and everything came back—all my problems and the challenges I was experiencing.

I eventually decided to quit my job and travel to all 17 Trappist monasteries in the United States. Over that six-month period, I talked with monks and nuns about silence and solitude and contemplative life. That led me to really shift the trajectory of my work and life into contemplative life and solitude—all these ways in which I really experienced the divine.

Long story short, this brought me into the Thomas Merton Society, where I got really involved. I was even the secretary for two terms. But something started shifting around 2018. I found a book of letters Merton wrote to friends in a bookstore. I opened it up and was kind of flipping through, and I saw the word “homosexuality.” I thought, “Huh. Thomas Merton never wrote about that. What is this?” I go to the page, and it’s Merton writing a letter to an “unknown friend.” It says, “Homosexuality is not a more ‘unforgivable’ sin than any other and the rules are the same. . . . Maybe psychiatric help would be of use.”

I was enraged and so disappointed. I was so hurt to think that this person whose wisdom I had yielded to thought sexuality to be a sin and that queer folks needed psychiatric help related to their being queer.

I realized that Merton has no idea what it’s like to be a queer person in America—or what it’s like to exist on the margins. He hasn’t had my experiences, so why should I yield to his wisdom? It made me reflect on all the other voices in contemplative live that I was missing, including my own.

Around this time, I was promoting my film Day of a Stranger, which was about Thomas Merton’s hermitage years. Every single time I showed the film, someone would ask, “How do we make sure younger folks hear about Thomas Merton?” Finally, I told someone who asked the question, “What’s so wrong with letting him go? What’s so wrong about letting new wisdom rise up?”

That’s actually one thing that Merton modeled—listening to folks from different experiences. He corresponded with people like Rachel Carson, Abraham Heschel, and D. T. Suzuki who had other types of wisdom. At the end of his life, he was really moving toward Eastern thought and Zen Buddhism.

Breaking up with Merton was important for me so l could recognize that I shouldn’t yield to leadership that has no idea what my experience is. But there’s a tension there—does that make everything Merton’s ever said obsolete? No, but it makes me discern what makes sense for me and what I need to leave behind.

I think all of us should break up with the status quo of our lives, because spiritual life isn’t meant to be comfortable.

This article also appears in the October 2024 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 89, No. 10, pages 16-20). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Unsplash/Jesse Bowser

Add comment