For our Sounding Board column, U.S. Catholic asks authors to argue one side of a many-sided issue of importance to Catholics around the country. We also invite readers to submit their responses to these opinion essays—whether agreement or disagreement—in the survey that follows. A selection of the survey results appear below, as well as in the October 2024 issue of U.S. Catholic. You can participate in our current survey here.

When I decided to convert to Catholicism in 1995, entering the church was tougher than I imagined. In the fundamentalist Protestant culture in which I’d been raised, new converts would be warmly welcomed, fast-walked through orientation classes and baptism, and assigned a mentor to shepherd them in the new community. Within months, the converts were indistinguishable from the old timers and were put to work mentoring their own flock of lambs.

By contrast, it took months of persistent effort and multiple forms of contact before I snagged the attention of the pastor at my neighborhood parish. During our first meeting, he kept his eyes trained on his notepad, muttered to himself (“not baptized, need to find a godparent”), and grunted in response to my answers. Finally, he gave me the contact information for the director of religious education, said he’d talk to a parishioner he thought might be interested in godmothering me, and sent me on my way.

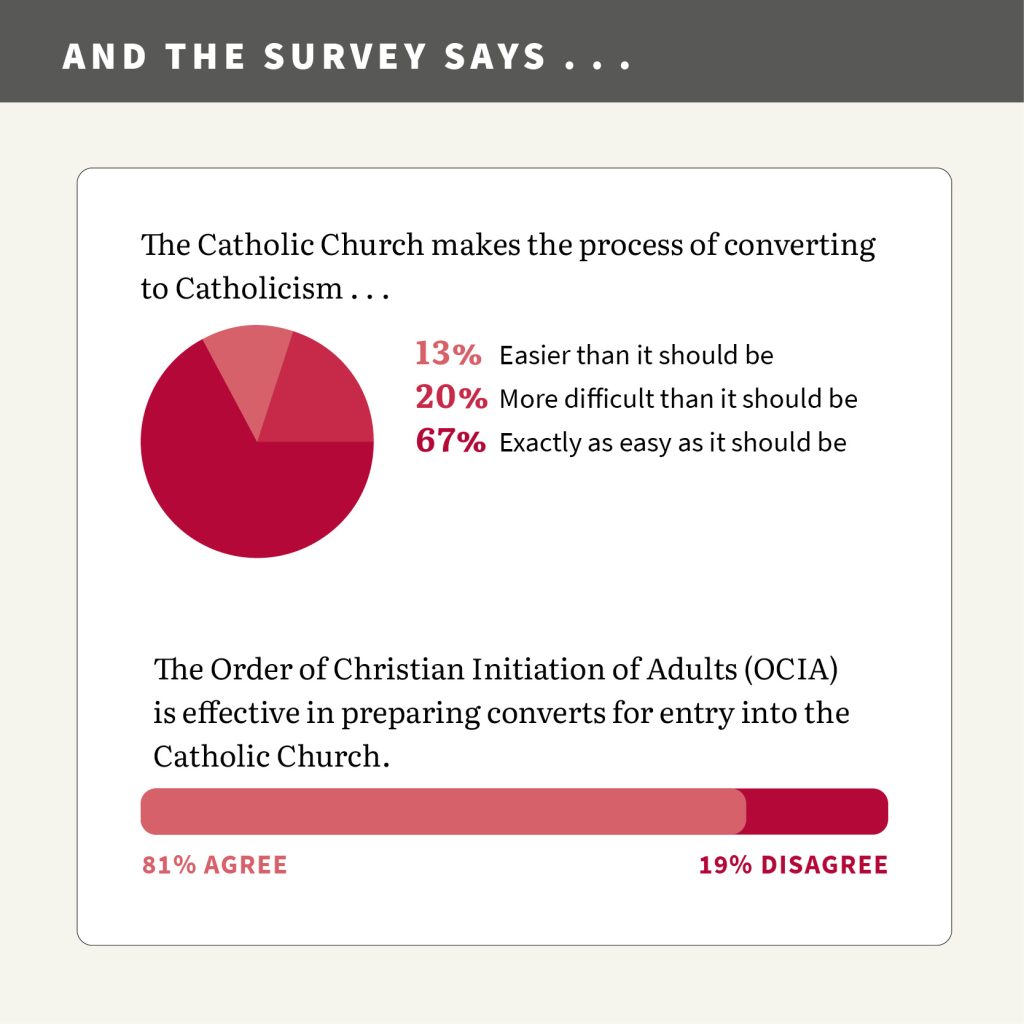

Months later, I found myself in the Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults (RCIA), a program that prepares people for entrance into the church. (In 2021, the program’s name was provisionally changed to the Order of Christian Initiation of Adults, or OCIA.) My godmother-to-be had given me a few books on Catholicism, which I’d been reading on my own. I was frustrated because what I was being taught in the class didn’t seem to align with the vision of Catholicism presented in the books. I called up the apologetics apostolate founded by one of the authors I’d been reading.

“I know a priest who would be willing to prepare you for conversion outside of the RCIA process,” a staff apologist told me. “You could be received into the church on a faster timetable.”

I have to admit, I was tempted. The benign apathy I’d been experiencing wasn’t fun. But after a few moments of thought, I said slowly, “No. Thanks anyway, but I think I should continue with the parish program.”

Nearly a decade later, I was a staff apologist for that apostolate and spent the next two decades observing conversions-in-progress in the United States. We responded to many of the same frustrations with the mainstream conversion process that I experienced, and the focus was on getting clients around roadblocks.

If a parish was putting the brakes on a conversion, we taught clients how to escalate the matter to the diocese—whom to contact, what to say, how to circumvent anyone raising concerns. If catechists appeared to undermine the Catholic faith (“I don’t say the word men in the Nicene Creed”; “Jesus didn’t really multiply the loaves and fishes, he was just teaching everyone to share”), we were right there to tell our clients their teachers were wrong.

Patience with the process, cooperation with parishes, and learning from those who challenged preconceived notions, were rarely, if ever, part of the OCIA journey. Once the conversion process was complete, new converts would be invited to share their stories publicly. After all, those stories could inspire new conversions.

We’ve been seeing the fruits of efforts like these in the last few years, especially with high-profile conversions. Actors Shia LaBeouf and Russell Brand, political commentator Candace Owens, and Tammy Roberts Peterson, wife of psychologist and author Jordan Peterson, are among the recent crop of Catholic converts. LaBeouf and Brand have both been accused of sexual assault. Owens has faced allegations of antisemitism from both the Anti-Defamation League and from Ben Shapiro, founder of the Daily Wire, a website for which Owens was a contributor. Tammy Peterson’s husband, Jordan Peterson, has long been controversial, especially for his views on gender identity.

In some cases, the holy chrism has barely dried on the foreheads of these celebrity converts before they’ve either announced thoughts of ordination (in the case of LaBeouf) or been given platforms for sharing their testimony (in the case of Owens).

There have also been plenty of conversions of entire church communities, usually brought into the faith by a charismatic clergyman who decides to swim the Tiber and bring his congregation along with him. That phenomenon was largely the reason Pope Benedict XVI established personal ordinariates in English-speaking countries for Anglican communities that desired union with Rome. Clergy converts often have a fast-track to ordination so they can continue to minister to flocks they bring with them.

All of this sounds great. If the heavenly host rejoices at the repentance of just one sinner, how much greater must be their joy to see all the saints marching into the church right now? Why should Catholics object to seeing lots of new Catholics?

The church has traditionally understood the conversion of the world to be its raison d’être, and it has always been open to receiving converts where they are. Perfection isn’t a prerequisite but an end goal. “The faith required for baptism is not a perfect and mature faith,” the writers of the Catechism of the Catholic Church say, “but a beginning that is called to develop.” At the beginning of the Christian journey is desire—either by the convert or by those who speak on his behalf, such as parents and godparents.

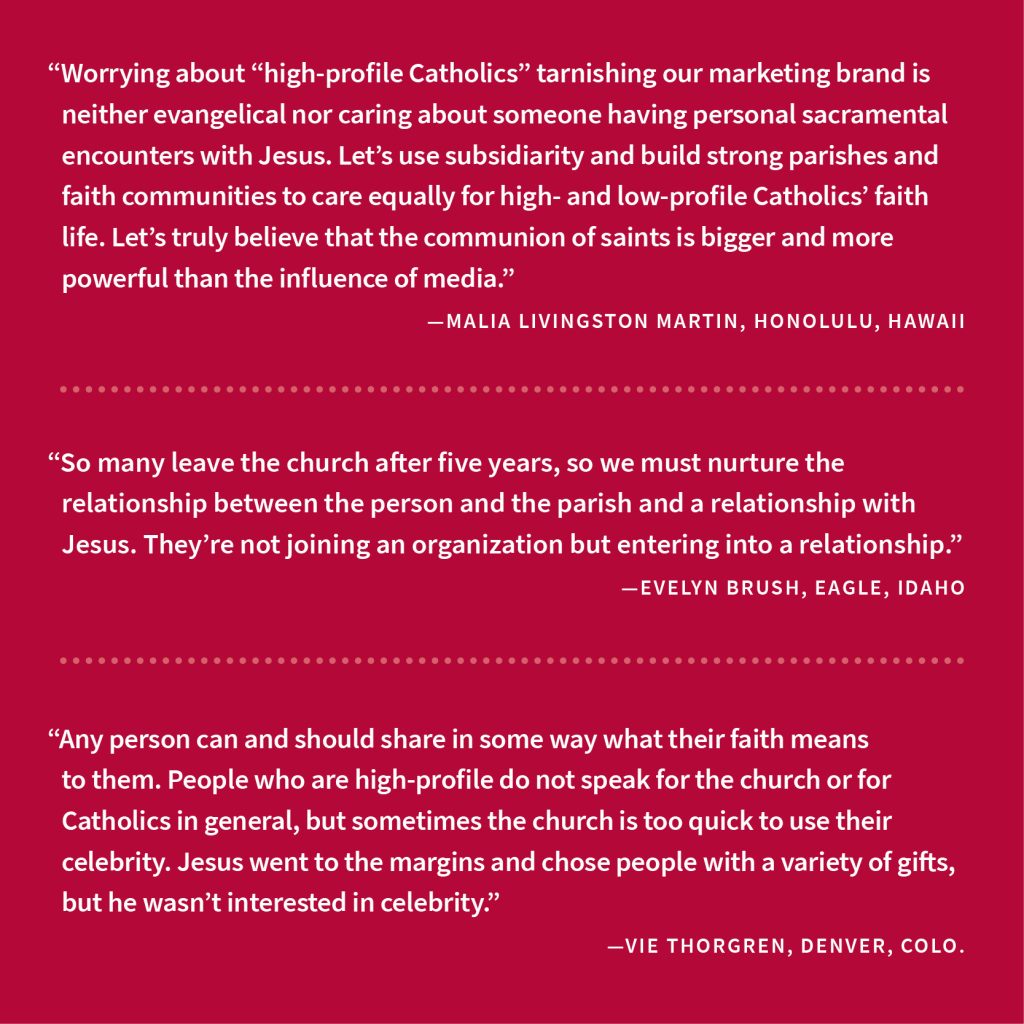

All people, whether famous, infamous, or anonymous, are welcome to join the church. That won’t change and shouldn’t. But that doesn’t mean that conversions should be fast-tracked without serious reason or that converts should be immediately tugged up on stages to share their stories with the world.

That same paragraph in the catechism that acknowledges the imperfect faith of new Catholics has more to say on the subject: “Faith needs the community of believers. It is only within the faith of the church that each of the faithful can believe.”

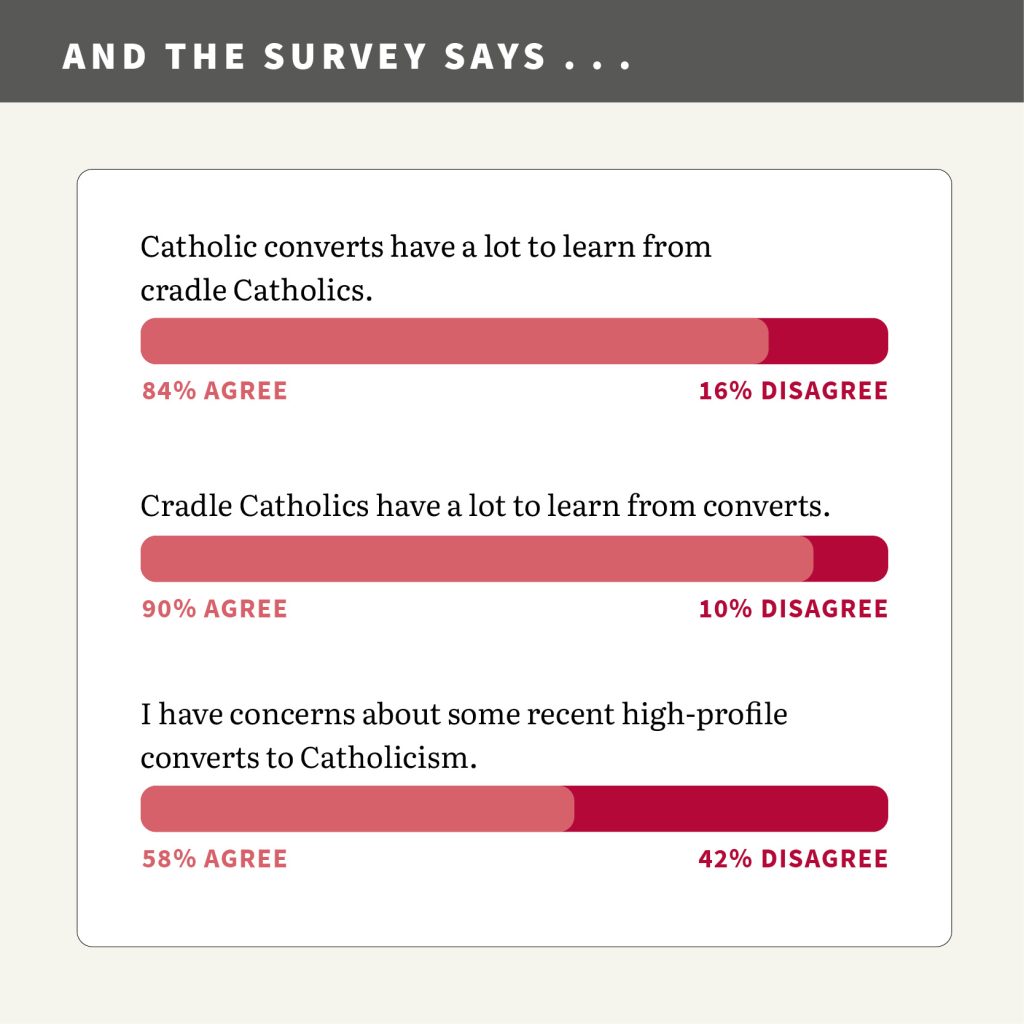

The community of believers holds an important role in faith formation. Short-circuiting the process in favor of quick conversions does the new convert no favors. Converts are isolated from their local communities and inserted into bubble communities—either those established especially for them, such as the Anglican ordinariate, or those created around the ideologies they held prior to conversion.

The ideological bubble communities often lionize their converts. The converts arrive to the sound of cheers. There’s no reason to reflect on past misdeeds, to consider reparation for past harms. Instead, the convert is placed at the center of the circle, urged to share their testimony and their pearls of wisdom.

This kind of adulation is harmful on many levels. Marginalized communities inside and outside the church begin to believe the celebrity convert embodies what it means to be Catholic. If concerns about public allegations of sexual assault or bigotry by new converts either go unaddressed or are waved away by church authorities, those at risk of assault or bigotry may begin to feel unsafe in the church. Parishes and dioceses often see an influx of converts who start pressing for positions of influence and authority. Sometimes converts are counseled to wait a while; other times, short-staffed churches and pastoral centers are desperate enough for volunteers to give new converts more responsibility than they can handle.

Finally, the adulation is harmful to the converts themselves. The honeymoon doesn’t last forever. Sooner or later, converts will experience the frustrations with the gap between their idealized Catholicism and the church in the real world. If they’ve scooted around those frustrations earlier in the process of conversion, they won’t have had the chance to fully consider before their formal commitment whether Catholicism was really for them. That’s when they’ll either reexamine their unchallenged notions . . . or try to remake the church in their own image and seek to bring their audiences along with them.

Perhaps more converts ought to be treated to the benign apathy I experienced during my conversion process: So, you want to become Catholic? That’s nice. You can find your local parish by searching online. It may be a while before the pastor can get back to you, but keep trying. Read a few books while waiting for OCIA to start up again. It may take a year or more to go through OCIA, but you can meet some nice people along the way. Listen to their experiences, ask them what they like (and dislike) about the church. Maybe volunteer for the parish bake sale or the Christmas crafts booth. Volunteering is a good way to meet people.

Sure, go to Mass regularly, if you can, but don’t sweat the differences between the liturgy in church and the liturgy in your books. The church allows for small changes in local areas.

Once you’re Catholic, settle into your parish and learn. It’s a lifelong journey filled with ups and downs, but hopefully you’ll have plenty of new friends in the congregation to help you on your way.

This article also appears in the October 2024 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 89, No. 10, pages 25-29). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Shutterstock

Add comment