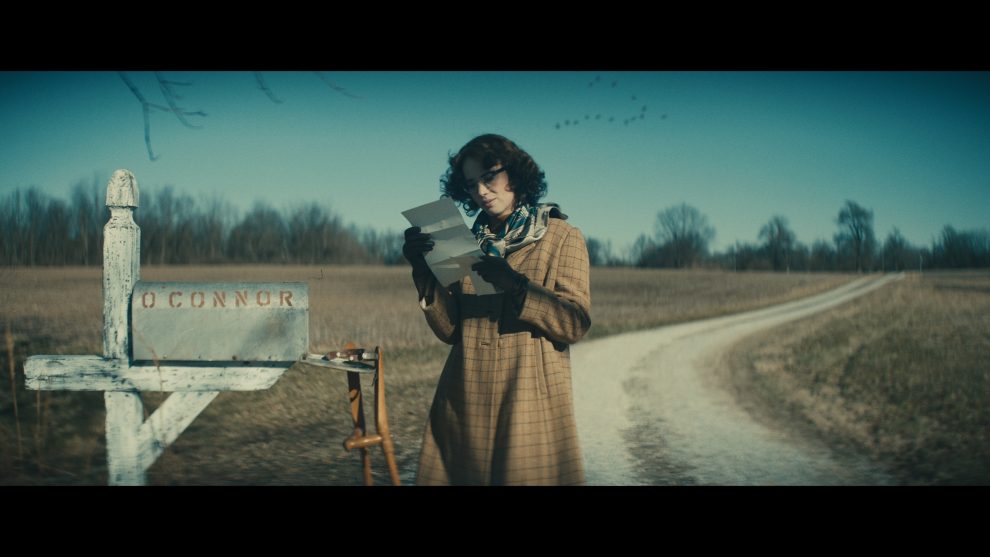

Ethan Hawke’s Wildcat opens, very nearly, with a familiar scenario: a dispiriting encounter between a young artist with an exacting creative vision and a conventional corporate gatekeeper with a checklist approach to what sells. The scene depicts a real-life exchange between 24-year-old Mary Flannery O’Connor (played by Maya Hawke, the director’s daughter) and her editor at Holt Rinehart regarding her unfinished novel Wise Blood, which the editor wants to conform to typical literary norms. “Sometimes I feel like you’re trying to stick pins in your readers,” he remarks and proceeds to make the same point twice more in different words.

Like a similar framing device in Greta Gerwig’s Little Women, which has Jo March trying to sell a story to a hardnosed newspaper editor, this scene in Wildcat can be seen as a filmmaker’s statement. “I’m amenable to criticism,” Flannery says, and then qualifies, “but only within the sphere of what I’m trying to do.”

She adds: “I feel that whatever virtues the novel may have are very much connected to the limitations you mention. . . . I’m not writing a conventional novel. Wise Blood, when finished, will be hopefully . . . just as odd, if not odder than the nine chapters you have now.”

If Hawke set out to make an odd film about an odd writer—perhaps even poking unsuspecting viewers expecting a conventional biopic—one of Wildcat’s oddest moves comes at the very beginning, before the movie proper. The first thing we see is a mock 1950s-style trailer for Star Drake, an imaginary adaptation of O’Connor’s short story “The Comforts of Home.” Plot elements are recognizable from the source matter (a typically hair-raising tale of parent-child conflict, in this case between an adult son and his elderly mother over a troubled young woman, identified as a nymphomaniac, on whom the mother takes pity). But the tone of the trailer suggests a lurid melodrama with little if any of the cultural atmosphere or spiritual resonance of O’Connor’s darkly comic, nondidactic, yet deeply Catholic work. An onscreen title then announces, “Our Feature Presentation.”

Is this over-the-top trailer a satiric indictment of prior O’Connor adaptations (for example, The Life You Save, the 1957 small-screen adaptation of “The Life You Save May Be Your Own,” which starred Gene Kelly and was ruined by a tacked-on happy ending)? Is Hawke skewering his Hollywood milieu as O’Connor skewered the pieties and foibles of the rural South? If so, this may also be an oblique acknowledgment of the difficulty of doing justice in a screen adaptation to so idiosyncratic a writer; it may even, perhaps, be a confession of Wildcat’s likely “limitations.”

Wildcat bills itself as “based on short stories by Flannery O’Connor,” though it could equally be said to be based on O’Connor’s letters (the source for much of Flannery’s dialogue) and her prayer journal (used to depict her prayer life in earnest voiceovers). The film is also, of course, based on O’Connor’s life, with biopic material so seamlessly interwoven with vignettes adapted from the stories that the same actors play several roles.

Laura Linney plays Regina, Flannery’s mother, but Maya Hawke and Linney also play mother and daughter in scenes from “The Life You Save May Be Your Own” and “Good Country People,” foregrounding the theme that autobiography plays a role in every writer’s work. (“Anybody who has survived his childhood,” O’Connor writes in “Mystery and Manners,” “has enough information about life to last him [as a writer] the rest of his days.”) Even the uniform barrel-lens distortion and blue-orange-hued cinematography make no distinction between Flannery’s inner and outer worlds.

The film’s various sources all converge most dramatically in an emotionally climactic scene as a bedridden Flannery pours out her heart to a wise, compassionate priest, played by Liam Neeson with a feathery brogue. The opening exchange about James Joyce overtly references a scene in “The Enduring Chill” where a stern, rigid priest named Father Finn visits a bedridden unbeliever. But Neeson’s character is not Father Finn but Father Flynn—the more sympathetic priest in “The Displaced Person” who visits the bedridden Mrs. McIntyre at the end of the story—and his pastoral style and sensibilities are the greatest contrast to Father Finn. Flannery’s agonized soul-searching draws upon O’Connor’s letters and prayer journal; Father Flynn’s enlightened responses likewise echo her own writing.

This dynamic alone is enough to make this scene a standout, not only in the film but in any ranking of the best cinematic depictions of pastoral counsel. I’m not sure O’Connor ever wrote a character as wise and inspiring as Neeson’s priest; I’m not sure it was in her nature to do so. (The Father Flynn in “The Displaced Person” seems like a good egg, but the story doesn’t plumb what his depths might be.) Throughout Wildcat, people try to offer Flannery well-intentioned advice like, “You could write about nice characters this time”; readers who agree might be delighted to encounter such a priest as Flynn in Flannery’s writing. Perhaps objectively this good priest should be critically deemed a “limitation” in Wildcat, and Ethan and cowriter Shelby Gaines should have given us a clerical character who feels more like pins stuck in the viewer.

If so, I apologize to Flannery fans for lacking the critical objectivity to disapprove of Father Flynn. Midway through the film is a sequence in which Flannery reads aloud “Parker’s Back” to a writing workshop mentored by the poet Robert Lowell (Philip Ettinger). (Maya adds the devout but capricious Sarah Ruth to her repertoire; Parker is played by Blindspotting’s Rafael Casal.) The story’s painfully raw finale is followed by a moment of something like stunned silence. Then one young man starts to say, “The thing I struggle with is—” Blessedly, Lowell instantly cuts him off: “There won’t be any critical dissecting this afternoon. Workshop’s over for the day.” I almost cheered. At its best, Wildcat made me feel, at least the day I watched it, the way few films do: critical of criticism rather than of the movie.

Sooner or later, of course, critical questions must return. Lowell throws a party where another student suggests to Flannery that she use the word Negro rather than “that other word.” She pushes back: “The people I write about would never dream of using any other word.” (The n-word is repeatedly used, mostly or entirely in scenes adapted from O’Connor’s fiction.) That’s a reasonable reply, but Wildcat’s overall treatment of O’Connor’s complicated relationship with race is misleadingly one-sided.

There’s no hint of O’Connor’s repeatedly expressed dislike of Black people (particularly what she called the “new kind” or “philosophizing prophesying pontificating kind, the James Baldwin kind”). Ethan Hawke is aware of the issue, and in a director’s note, he discusses his initial questions about doing the film, ultimately asking, “Is there a place in today’s cultural climate to tell the stories of brilliant, tormented people who also display abhorrent prejudices?” It seems to me that an affirmative answer should be qualified in the film by some kind of acknowledgment of the abhorrent side of the equation.

Wildcat does highlight O’Connor’s gleeful literary deconstruction of the culture of American racism and white supremacy, pointedly contrasting the ugly, ridiculous bigotry of matronly women (usually played by Linney) with the more enlightened views of younger characters played by Maya. (These are usually daughters, although bookish Mary Grace in “Revelation” is unrelated to the bigoted older woman whom she attacks, growling, “Go back to hell where you came from, you old wart hog.” In “Everything That Rises Must Converge,” the young son Julian becomes an androgynous “Jules.”)

This intergenerational dynamic is reinforced by Flannery’s own awkward discomfort with her mother and her aunt Katie Cline (nicknamed “Duchess” by Flannery, played by Christine Dye), who wish that Flannery would aspire to be another Margaret Mitchell and gaily enthuse about Hattie McDaniel’s “respectable Negress” in Gone With the Wind. (This scene is one of the film’s most O’Connoresque moments, comically icky if not fully grotesque.)

I like the dovetailing of the generational conflicts in “Revelation” and “Everything That Rises Must Converge” with Flannery’s interactions with her mother. I also admire the sound editing in these sequences (playing the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” over “Revelation” and continuing the choral singing from Flannery’s church over the action in “Everything That Rises”).

There are other clever touches. When Flannery, beginning to suffer from the lupus that killed her father and will kill her at 39, first tries out her late father’s crutches, the movie plays the audio from a celebrated newsreel clip representing young “Mary O’Connor’s” first brush with fame in connection with a backward-walking chicken, which is, of course, how Flannery now feels. Much later comes a brief magical-realism flourish (not an O’Connoresque flex, to be sure) referencing, you know, a bird of a different sort.

Wildcat isn’t as odd as an O’Connor story—or as that early scene at Holt Rinehart perhaps suggests it wants to be—but it brims with passion and integrity. I’m grateful that it exists.

Image: Oscilloscope Laboratories

Add comment