Few artists can weave together theological, cultural, and aesthetic values as gracefully as Janet McKenzie does. As with many great masters, she makes the most complex things appear simple, elegant, and natural. She came to prominence in 2000 after winning an international National Catholic Reporter competition that asked contestants to portray Jesus for the new millennium. Her now iconic painting, Jesus of the People, initially incited hate mail and threats. A quarter of a century later it has become an exemplar of the global and “catholic” church toward which we strive.

As a testament to her vision, McKenzie’s work also speaks to a wider Christian and even non-Christian audience that is concerned with the dignity of all people, particularly with issues of gender and race. The Basilica of Saint Mary in Minneapolis, Minnesota recently featured her work in a retrospective, and paintings such as Jesus of the People are regularly used for LGBTQ causes and social justice movements. Theologians such as Elizabeth Johnson and Joan Chittister as well as writers and activists such as Joyce Rupp and Helen Prejean have heralded her artwork. Palliative care physicians such as Dr. Phylliss Chappell use McKenzie’s art to help people approach the end of life. And yet McKenzie’s sacred art is still finding its much-needed place in the church.

Your art has been in the public eye for many years, especially since your groundbreaking painting Jesus of the People. What led you to become an artist?

I was one of those children that needed to create to express myself, perhaps because I didn’t feel 100 percent understood or heard. I only saw my mother cry twice in my life: Once was when I was 13 and my father had a heart attack. The other time was when I was 10 years old and my art teacher exhibited art that other children at my school and I had created.

I had made a little sculpture of a man, and the teacher took my mother aside and said, “This is very good. Janet has some talent.” When we left, my mother wouldn’t let me carry the statue, because she was afraid I would break it. When she got in the car, she hit it on the steering wheel and it broke and she wept inconsolably. The fact that one of the few times she cried in my life was when a little sculpture I made broke has stayed in my heart all these years.

Another formational stage in my life occurred when studying abroad in Europe on a scholarship. My mother was dying, and my grandmother had cancer. I came home to help my father on Christmas Eve. On February 5, my grandmother died and on February 24, my mother died. I stayed with my father, and then 10 months later he died of a heart attack while alone with me. I was only 23.

My other grandmother, my father’s mother, fell apart when my father died, and I wound up being her caretaker. While dealing with that, I got married and became pregnant with my first child. So those early years were terrifying. I didn’t know how to hang on to my path as an artist.

A lot of people have written about your insightful depictions of femininity. What draws you to feminine subjects?

It began with my grandmother, who was a real heroine and inspired me. In her I see Mary, who’s so iconic. My grandmother in essence was that. She loved me selflessly and was present for me and protected me. And so it was quite natural when I finally committed to working with sacred art that I had a strong desire to paint Mary.

What are you trying to convey about Mary in your work?

I want to portray the timelessness of the maternal and how inspirational Mary is to women across time. Women who are in desperate straits turn to her in prayer, and she’s always present to them. Certainly my grandmother in her own way was that for me, as was my mother.

I recently found out about this apparition that happened in Vietnam, Our Lady of La Vang. I was so moved by it that last year I did an interpretation where she appears in different ways at different times. I find that important and beautiful.

One thing that really strikes me about depictions of Mary in film is that they always tend to show people who have nowhere else to turn. Mary becomes a source of hope and strength.

Oh, that’s exactly right. I can relate to that. When I wanted to paint sacred art, I didn’t feel I had a right to, because I wasn’t raised in the Catholic Church. I felt like I had nowhere else to go, because I wanted to do this work so badly but I needed help in moving forward to the next step.

There was a priest here at the time, a second-career priest who was in his late 60s and had been a parole officer at Sing Sing, Father Richard Fowler. We spoke about it, and he was so kind and loving. He told me I had a calling and I needed to follow it. I just couldn’t make that jump, and he helped me.

Can you share more about your desire to paint religious subjects?

In the mid 1990s, I reached the end of the work I was working on. It was no longer satisfying. And I knew the reason was because I wanted to paint sacred religious art. And that’s when I spoke with Father Fowler. I did my very first painting for him, and then it moved on from there. A couple of years later I learned about the Jesus 2000 competition in the National Catholic Reporter, and that’s when I did Jesus of the People.

This longing to make sacred art—how did you name that for yourself? What is sacred art to you?

I wanted to paint Mother Mary. I wanted to work with halos. I wanted to be absolutely clear that this was sacred art. And I was so afraid of being overexposed and that I would reveal way too much of myself. I had been holding myself back.

Really, the essence of what I do is very simple. I create art that honors the fact that we are all created equally in God’s likeness.

A lot of your paintings portray parenthood, especially images of Mary and Jesus as a child. Why is this theme important to you?

I am a mother. I’ve had a child. And my baby is now a son to whom I turn for expertise. He is a partner in my work and on my life journey. I know this path, and the reflection of the mystery and miracle of life is breathtaking.

In 2019, I was invited to Albuquerque to be a presenter at the Universal Christ Conference at the Center for Action and Contemplation. There were 2,300 people present with another 2,800 attending virtually. They created this darkened gallery space people transitioned through as they entered into the enormous conference center. It was an absolutely breathtaking and beautiful experience to watch people decompress and sit with my work.

Many men came up to me asking if they could speak privately with me about one particular work. It was my painting called Joseph and Jesus, and it depicts Joseph holding Jesus. They whispered, they were very quiet, but they each said the same thing. Each man was raising children alone, and they felt so uncelebrated and underacknowledged and the painting somehow spoke to them about Joseph’s love for Jesus, similar to the love they have for their children or child. They thanked me for this work and brought me to tears. It was so heartfelt.

And so I have tried to focus on parenthood in an inclusive way, motivated by my own father who’s sacrificed so much and my son, Simeon, who is such a nurturer. I really feel it’s vital to put art into the world showing men as nurturers so that young men will feel this is appropriate. It is appropriate, good, and loving to be nurturing in life.

I always want the work to be invitational. I always say I want to be like Jesus of the People. I’m going to always remain loving. It’s not easy a lot of the time, but I have attempted to maintain that position.

Race and gender are important aspects of your art, with the holy family, saints, and religious figures represented in a wide array of racial and cultural contexts. Can you share about your choice to do this?

I believe that every one of us on Earth is given talent in one way or another, and it’s important that we use it for good. There’s really nothing like coming to know how you can be most useful. I feel blessed to know that. I’ve seen the power of how visual art can affect people. There’s nothing like visual art to give a concrete form to imagery, which is helpful to people because it becomes a jumping-off point in how they may or may not visualize something. It shows them their boundaries.

My hope is that my art will move in the world and remind everyone that we’re all sentient beings. I feel my greatest service to this life and the talent God gave me is to bring awareness to the importance of loving one another, to be a force against hate, racial prejudice, and racial injustice. It probably sounds so idealistic, but it is what I believe.

I think your art does a wonderful job of helping people be seen, valued, and celebrated, but at the same time it also challenges.

Well, that’s the other side. There’s been a lot of negative reactions to my work, particularly Jesus of the People, to the point that people hated the art and hated me. The hate hasn’t ever stopped, although it’s nowhere like it was 20 years ago.

Your art really speaks about the reality of the incarnation, that Jesus took on our humanity. To have such negative reactions makes me think that there’s a failure to really understand the meaning of the incarnation.

I totally agree. But I have come to learn that hate comes from fear. I had a woman contact me and say that nobody was going to take her image of Jesus away from her. It was Warner Sallman’s Head of Christ, and she was a Black woman, and she was extremely angry at me. I’ve come to understand that imagery reaches the heart of a person, and they need it, and it provides something that they don’t want to let go of.

Jesus of the People was never meant to replace imagery that has provided comfort to people. It’s remarkable, and in a way inspiring, because the reaction reveals the power of art. Even if people hate my interpretation, they love another one and will not let go of it because it provides them comfort, and I’m glad for that.

The Rev. Jonathan Walton, former pastor at Memorial Church and now president of Princeton Theological Seminary, shared his response to Jesus of the People and why he invited me to be the William Belden Noble lecturer in 2013. He said he was so appreciative of Jesus of the People because of all of the young Black children in churches trying to adjust to seeing only white imagery of Jesus that they couldn’t see themselves within. I know that’s why, all of these years later, I get so many requests for prints. Not one week goes by that I don’t get a request for something having to do with Jesus of the People.

As we are talking about Jesus of the People and representation, do you use models for your paintings?

I use models, and I get so attached to them. I come to know them and love them, and I start seeing them as subjects in everything I do. And then sooner or later I have to let go of them because not every painting can be of them. I invariably stop having models stand in front of me so I can work away from them. Personally, I am not at all interested in being a portrait artist.

When I did Jesus of the People for instance, I did not need Maria, one of my models, to pose for me. My goal was to bring the male and female aspect as close together as possible, because I believe Jesus is both masculine and feminine. And I knew if she was standing before me, I’d have to paint Jesus as feminine because Maria is such a feminine person.

As far as my style, I have no interest in the background or painting a logical landscape. And I have no interest in clothing that reflects a specific time. For me, everything is timeless.

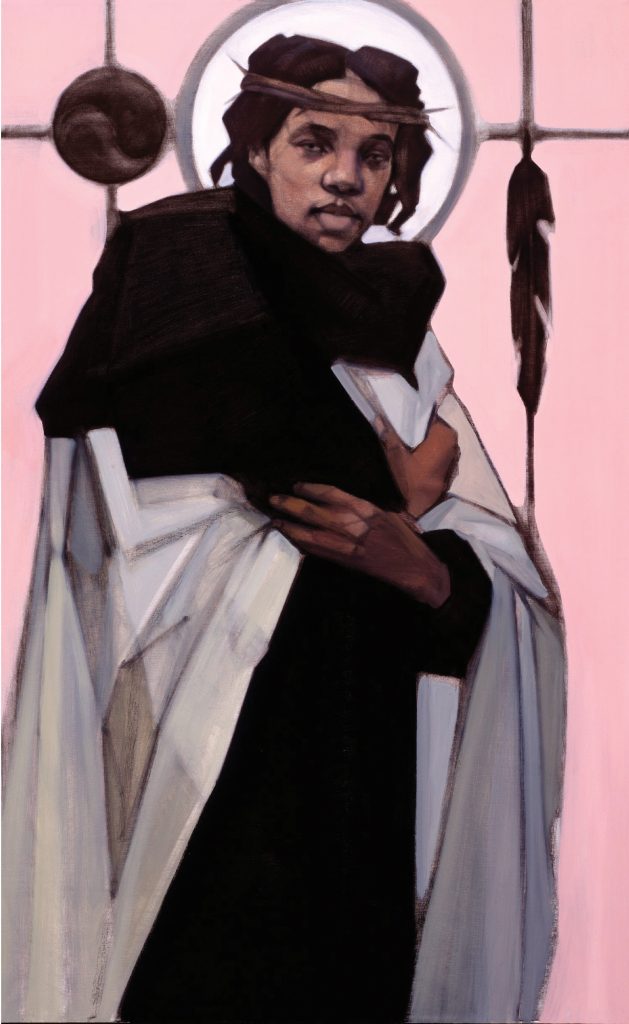

I also work with line in a certain way that leads everything upward. All my art is heaven oriented. My work is actually really abstract. Everything in the painting—the panels of color; the horizontal lines, which are often crosses; the thin vertical lines; flowers; or other forms—every single thing serves to support the emotional voice of the figure. Everything is painted with the goal of reaching the emotion of the face and the stance of the figure and the position of their hands.

You communicate a lot with facial expression and bodily gesture. Could you speak about your frequent choice to portray people with their eyes closed?

A few years ago, I just reached a point where I needed to close my subjects’ eyes to reflect that the art is really a visual prayer. It’s almost as if the paint, the canvas, all the practical things that bring this forward are unimportant. Everything about a painting goes to heaven, to God, to where words fail.

I thought I’d lose everybody, that people would turn away from my work because they would feel blocked out, but that’s not what happened. I might have sold my viewers short, but they took that journey with me and told me, “That’s exactly how I feel. I get this, I understand this. This is prayer.”

Is there a painting you’re particularly proud of?

I have to say Jesus of the People. It’s just made such a difference in the world. Twenty-four years later, it’s still speaking and affecting positive change. I never expected anything like that to happen.

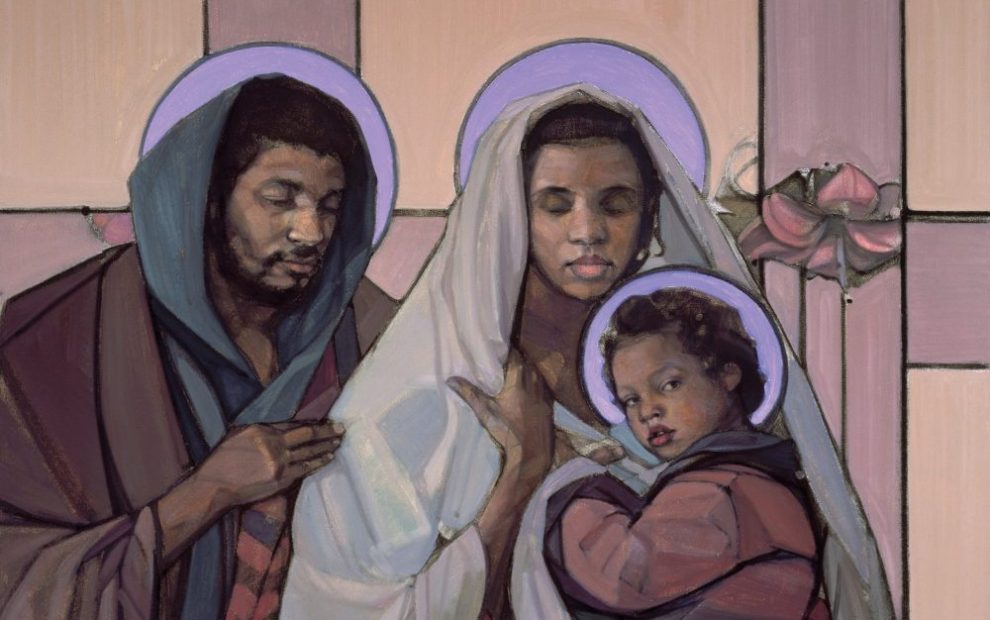

There are two more paintings I could mention. One is The Holy Family. The Holy Family has been impactful because it was the first time I painted Joseph as integral to the holy family. So many people love it and tell me how meaningful it is. The other work is Elijah Hears the Still Small Voice of God. I wanted to paint that moment when Elijah realizes that God has been with him all along. It’s only past the wind and the fires that he’s finally able to hear the still, small voice of God, and I certainly have experienced that in life.

I needed a model and I didn’t know who I would find or ask, and I realized I had the perfect model in my son, Simeon, because he’s a very special man. He’s not at all religious, but he is incredibly sacred and spiritual and just innately in touch with God. I asked him if he’d pose for it. Of course he said yes, and he gave 100 percent, and it comes through in the painting. Somehow you can feel our love, the bond between us.

A woman in Australia wanted to buy it, so I asked him, “Well, what do you think? Should I let it go?” And he said, “Yes, Mom, let it go out into the world to do the work it needs to do.” So I did.

What do you hope your images will accomplish?

It’s fairly simple: I hope people will find deeper love for one another and stop, take a moment, look at the subject in the painting, and find a reflection of themselves, no matter their race or gender. It’s the emotional connection to the viewer that I hope over time will contribute to a better world.

This article also appears in the April 2024 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 89, No. 4, pages 20-25). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

All images by and courtesy of Janet McKenzie. Header image: The Holy Family

Add comment