’Twas the night before Christmas, when all through the house, not a creature was stirring; well, except for Billy, the psychopath hiding in your attic. No, that’s not how it goes. Let me try again. ’Twas the night before Christmas, when all through the house, not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse. That’s right. The stockings were hung by the chimney with care, for fear that Krampus soon would be there to kidnap your kids. Huh, no, that’s not it either. Although I’m pretty sure it involves a suspicious folkloric figure breaking and entering by way of your chimney.

’Tis the season to cue up A Christmas Story, bake your favorite holiday cookies, and hit repeat on Mariah Carey’s “All I Want for Christmas is You.” Right? Why would you want to entertain anxieties about serial killers and other assorted monsters? Horror is for Halloween, isn’t it? Believe it or not, historically speaking, the macabre has played an important role in our yuletide celebrations. The weird and the bloody lurk just beneath the surface of our most saccharine (and consumerist) holiday. Christmas and horror go hand-in-hand.

Silent night, deadly night

For the uninitiated, Christmas horror flicks have been a thing for a while now. While some are busy debating whether Die Hard counts as a Christmas movie or adjudicating the merits of Love Actually, others jump and laugh and scream at their favorite seasonal slasher. These winter fright fests have something to teach us, too. In The Krampus and the Old, Dark Christmas: Roots and Rebirth of the Folkloric Devil (Feral House), Al Ridenour argues that films such as Silent Night, Bloody Night and Black Christmas offer an important subversion of “our notion of the holiday as cozy domestic idyll.”

This subversive tradition’s roots run deeper than campy Christmas horror movies such as Christmas Evil and Gremlins might imply. Even if they’re not your cup of cocoa, Ridenour reminds us that “Christmas requires the darkness.” Children know this intuitively. “The holiday we’ve spun from sugarplums and annual TV specials can’t exist without those dark edges where imagination blooms.” Santa won’t come unless you’re sound asleep, or so we admonish our kids each year.

And it’s not a coincidence that this particular holiday coincides—at least in Europe and the Atlantic world where our peculiarly American Christmas cult was born—with the coldest, darkest days of the year. The safe and sweet Christmas we’re accustomed to today is a relatively recent invention. Much older is the notion that December is when monsters stalk the night threatening punishment and the veil between ours and the spirit world is especially thin.

Scary Santa

But what of “Jolly Old Saint Nick”? You know, the one with the plump belly and rosy cheeks who cheers up children the world over? Turns out our familiar image of Father Christmas as an old man sporting a big white beard and red fur coat is not much more than a century old. Our standard-issue American Santa Claus was canonized by mid-20th-century artists such as Haddon Sundblom, who painted him for Coca-Cola advertisements. Before that it was Thomas Nast (also known as the father of American political cartooning) who solidified Santa’s defining visual features in the pages of Harper’s Weekly in the late 19th century.

If we dive deeper, past the Claymation cartoons and Victorian poetry, we find something much more disturbing. Yes, St. Nicholas of Myra (c. 270–343 CE) was a bishop of the early church who helped codify the Nicene Creed. Yet his legacy as the patron saint of children has more to do with the legends—horror stories, really—that circulated after his death. One goes like this. Once upon a time, three boys made the fatal mistake of stopping at the wrong inn. There an evil inkeeper killed the boys, chopped them up, and threw them in a pickling barrel in hopes of hawking them as meat for sale. Thankfully, our saint arrived just in time to solve the mystery and miraculously put the boys back together again, alive and unspoiled. Gothic tales such as this were common features in the Roman Catholic medieval iconography of the saint. Removed from their religious context, they sound like something from a horror movie script.

The monsters of Christmas

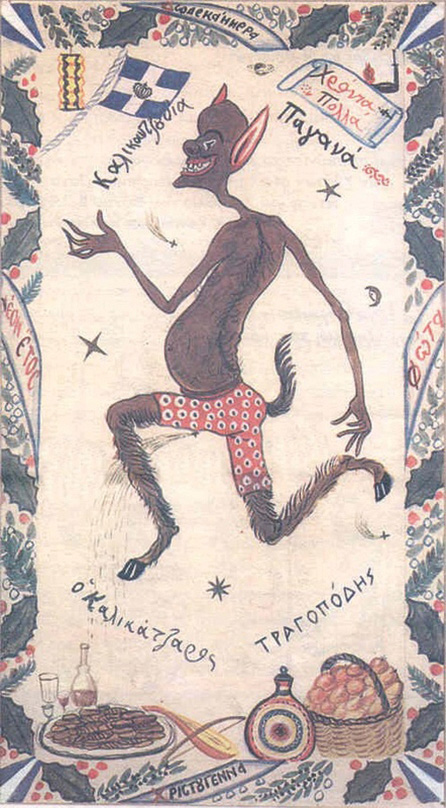

In many European cultures, St. Nicholas came to be associated with other mythic creatures as well. Enter Krampus, who has experienced newfound appreciation in some quarters as a countercultural way to commemorate the holiday. Today Krampus tends to be imagined as Santa’s satanic antonym, a demonic beast who whips and steals naughty children. This is how the studio film Krampus portrays him: as an anti-Claus, Santa’s evil opposite.

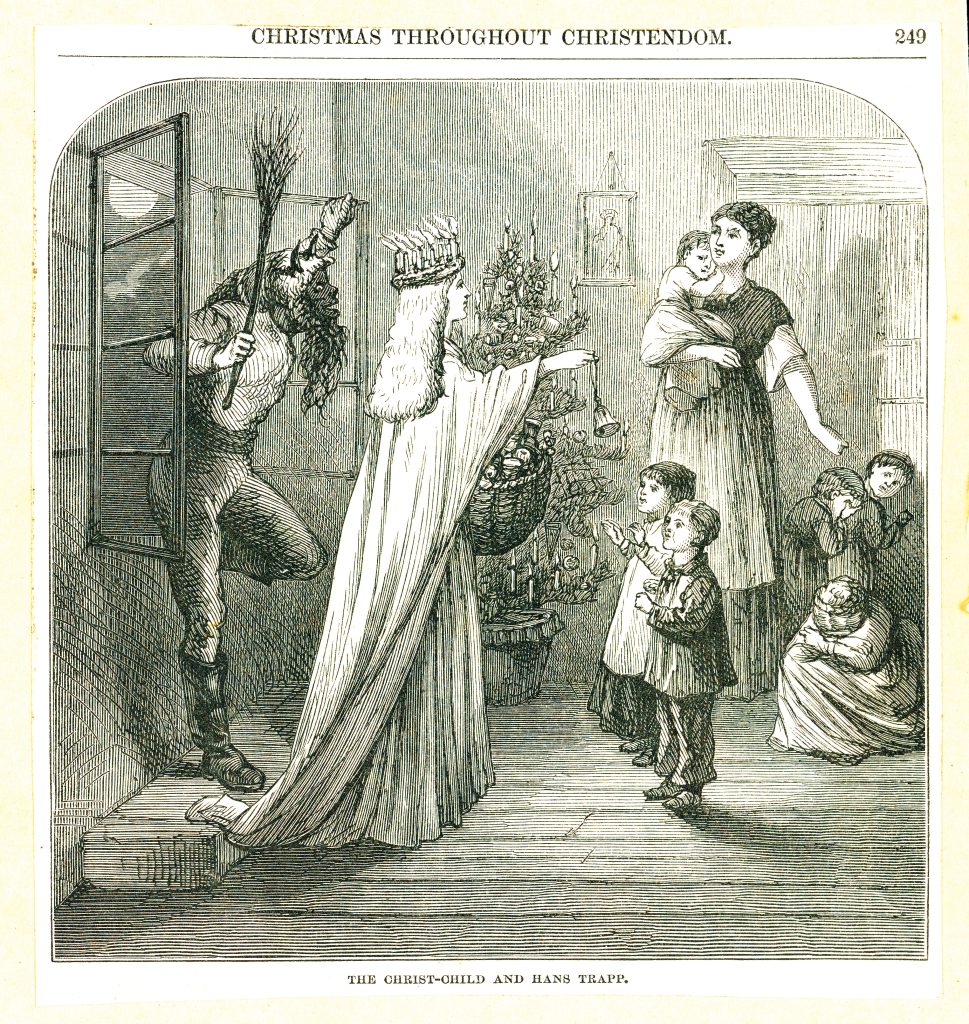

Ridenour notes, however, that this is a misconception. “Krampus” is not a proper name so much as a class of entity (like “vampire” or “werewolf”). Krampuses likely share their origin with other bogeymen. “[T]he idea of a threatening figure paired with the giving of rewards clearly meets a pragmatic need felt by parents worldwide,” Ridenour hypothesizes, namely, to raise children who “say their prayers, mind their manners, [and] go to sleep on time.” Medieval mummers brought krampus to life in physical form as part of Christmas pageants, and, in Catholic Austria and Bavaria, these krampuses bore striking resemblance to medieval imaginings of the devil: horned, hooved, and hairy. They still do (and you can vacation to see them on parade)!

Holiday home invasions

This history may help you appreciate why so many of our most beloved Christmas classics hinge on darkness as well. The most obvious example is Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol and its innumerable interpretations. It is, after all, a literal ghost story. In fact, it is all that remains of the once popular pastime of Christmas ghost stories. This practice, particularly in its Celtic context, reflected the sense that Advent was a “thin space” in time, when we humans have more than the usual access to the spirit world. Hence those ghosts of Christmas past, present, and future wreaking havoc on Ebenezer Scrooge’s humbugging routine. Even The Muppet Christmas Carol insists on frightening its young viewers. The two trusty comedic narrators abandon the audience in the penultimate scene as a trembling Rizzo the Rat declares to the Great Gonzo: “This is too scary!” Come for the puns, stay for the terrifying 8-foot-tall muppet with overlong arms who looks like Sister Death and silently leads Scrooge to his grave.

Christmas horror isn’t limited to Dickensian hauntings either. Home Alone is a home invasion movie at its core, albeit one that plays off horrific violence as slapstick physical comedy. How the Grinch Stole Christmas! is a creature feature of a kind, with the devilish cave-dwelling Grinch bearing a faint resemblance to the maleficent horned krampus. Even It’s A Wonderful Life—the GOAT Christmas movie (fight me)—is nothing without its shadows and paranoia. That final act, in which its hero attempts suicide before being supernaturally thrown into a world where he never existed, feels a lot like a Hitchcockian thriller. And so, while many will remain blissfully ignorant of serial-killing Santas and krampuses prowling about the world seeking the ruin of Christmas, it’s not hard to see some horror seeping out of the cracks in our most beloved classics.

At the end of the year, some of us simply prefer our Christmas cheer muddled with memories of the dead (as we prefer the original, mournful lyrics to “Have Yourself A Merry Little Christmas”). We come by it honestly and with quite a bit of history to back that up as well. And, for those of us who are Christians, this gloom heightens the joy that enters the world on December 25. The cold descends. The Earth dies. Monsters and spirits walk amongst us. And God enters the world as a human light shining forth in that darkness.

This article also appears in the December 2023 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 88, No. 12, pages 15-18). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Header image: Wikimedia Commons/Luca Lorenzi. In regions of Austria and Bavaria, hooved and horned krampuses are still part of seasonal pageants.

Add comment