It is common today for Catholics to use the Marxist label as a slur—or, less frequently, as a sign of activist credibility. Yet most Catholics lack even a foundational familiarity with Marxism. Catholics who want to understand both the basics of Marxism and legitimate critiques of it would do well to learn from St. Pope John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI, both of whom recognized the merits of Marxism while criticizing its faults.

But why understand Marxism when Catholics already have Catholic social teaching? While the social doctrine of the church is a rich resource, there is no reason not to enrich it further—as Plato enriches Augustine and Aristotle enriches Aquinas. Marxism offers original analysis of political economy and historical injustice that can significantly enhance our Catholic understanding. Following Popes Benedict and John Paul II, we can learn not only from their famous criticisms of Marxism, which are grounded in intellectual sympathy and rich in historical context, but from their appreciation of Marx as well. And perhaps we can even learn a few things from Marxism itself.

Both Pope John Paul II and Pope Benedict frequently lament that Christianity failed to rise to the historical moment with a ready and viable alternative to Marxism. In other words, Marxism provided a strong critique of the real harms of the Industrial Revolution, but the church responded too late and too weakly. And the Catholic Church’s response to fascism was tepid compared with that of the liberal and communist societies, which were far more willing to openly oppose the evils of fascism. While anti-fascism was present in the church, it was by no means dominant. And, in some cases, Catholics even allied with fascists.

Pope John Paul II survived both the Nazi and Soviet invasions of Poland. But even though he was a steadfast enemy of communism throughout the Cold War, this did not default him into a free marketeer nor a promoter of capitalism. In 1991, he wrote Centesimus Annus (Commemorating the Centenary of Rerum Novarum) to mark the 100-year anniversary of the first social encyclical, Rerum Novarum (On Capital and Labor). In that work, the focus is less on the century-old encyclical it celebrates and more on the state of Europe and the world in a post-Cold War reality.

Though Pope John Paul II is deeply critical of Marxism in this encyclical, he does point out that Christianity needs to address certain Marxist moral and ethical ideas and principles (class struggle, universal human rights, and the rights of workers). He vindicates Marx’s social diagnoses of unjust and exploitative labor practices while departing from the Cold War’s prescriptions of Soviet communism.

During World War II and prior to the Cold War, communist and liberal societies allied to stop the rise of fascism. In the aftermath of that victory, when Western liberalism’s truce with communism ended, the Cold War began. In the church, this was also the period that led to the Second Vatican Council, where Pope Benedict, then Joseph Ratzinger, played a pivotal role. He also worked as a professor during the student protests of 1968. These movements soured his attitude towards those he perceived as radicals. Many other German intellectuals, including many Marxist critical theorists, were similarly dismayed by these protesters

But Pope Benedict’s criticism of Marxism was not born of ignorance nor was he incapable of appreciating Marx’s ideas. In Spe Salvi (On Christian Hope), Pope Benedict writes, “With great precision, albeit with a certain one-sided bias, Marx described the situation of his time. . . . His promise, owing to the acuteness of his analysis and his clear indication of the means for radical change, was and still remains an endless source of fascination.”

In the dawn of a new millennium following the end of the Cold War, Pope Benedict often made retrospective remarks on the history of Europe and consistently affirmed the moral diagnosis of Marxism while rejecting many of its political prescriptions.

The value of Marx’s moral diagnosis lies in his cataloging of material abuses and exploitations that industrial society inflicted upon its workers. These abuses included the routine use of child labor, no limits to the working day or week, and other exploitative practices that violated the dignity of persons and resulted in wretchedly low life expectancies and precarious health. Marx also identified the connection of labor injustice with the exploitations of colonialism, as robbing workers of their dignity and time mirrored the practices of enslavement and Indigenous dispossession.

The political prescriptions of Marxism include various forms of direct action, and discussions about appropriate action have frequently led to debates on the extent to which violence can be justified. Thanks to the just war tradition, these justifications are nothing new to political philosophy, including Catholic thought, but Pope Benedict rejected such prescriptions wholesale.

Pope Benedict’s attitude on these matters might be chalked up to his working-class German upbringing during World War II. Many do not know that his Bavarian Catholic family was firmly anti-Nazi and that he eventually deserted his conscripted post in the Nazi army.

Given that both popes were able to criticize Marxism while still affirming much of its social criticism, it seems reasonable that Catholics should learn to take Marxism seriously and learn both about and from it.

One thing we can learn about Marxism is its pivotal role in political history, from the writings of Marx in the mid-19th century through the rising and falling revolutions, alliances, and totalitarian regimes (and alternatives to those regimes) and social movements into the present. Marxism has also had an important influence on both Pope Benedict’s and Pope John Paul II’s views on political history. Catholics, especially in the United States, can take a lesson from them and listen to these Marxist disputations. For example, the Black Intellectual Tradition in the United States has a long history of engagement with Marxism, from W. E. B. Du Bois to critical race theory to Black Lives Matter. In each case there are important continuities with and also serious departures from Marxism. Understanding the relation of Marxism to the U.S. history of civil rights is important for Catholics to grasp.

Something that Catholics can learn from Marxism, following both Pope John Paul II and Pope Benedict, is to take labor and economic injustices seriously.

For example, in Capital, Marx uses examples of the abuses of industrial capitalism in British factories that not only rob people of their just wages but, more drastically, take time from their lives. He notes the short life expectancy of working children and opposes child labor and advocates for limits to the work day and week in policy and law. Marx also offers an incisive analysis of colonialism in Capital, especially the institution of chattel slavery in the United States. He also argues that colonialism is part of the structure of the industrial capitalism born in the mother country and imposed upon Indigenous peoples in the Americas.

Many Catholics today draw on the church’s social teachings to promote social justice and the common good. This includes addressing the precarity of workers and the temporal conditions of work and the continued impact of colonialism upon Indigenous peoples. Others reject these contributions because of the evils of communist Marxists such as Stalin, Mao, and Pol Pot. There is no question that these regimes are part of the political history of Marxism and that they fly in the face of its concern for human dignity. One would think that serious Catholics would be capable of working inside a mixed moral and political legacy. After all, our own church history, especially in the recent wake of sexual abuse and reckonings with colonialism and enslavement (not to mention the growth of authoritarian and neofascist Catholic ideologies and alliances), is decidedly mixed. We are already accustomed to working with moral and political complexity.

And there is a vibrant tradition of post- and anti-communist Marxism that takes seriously the histories of abuse and mass killing as well as questions of violence and authority, from the Frankfurt School (especially Herbert Marcuse) to Latin America liberation theologians such as Gustavo Gutierrez and Leonardo Boff to African socialists such as Servant of God Julius Nyerere.

Catholics ought to try to learn about and from Marxism, and not just to get the facts straight. The failure to address political history accurately weakens our social and political witness and places us in a position of smug naivete. This is a scandal to the richness of our intellectual tradition and a badly missed opportunity to find a way to share the gospel in our time.

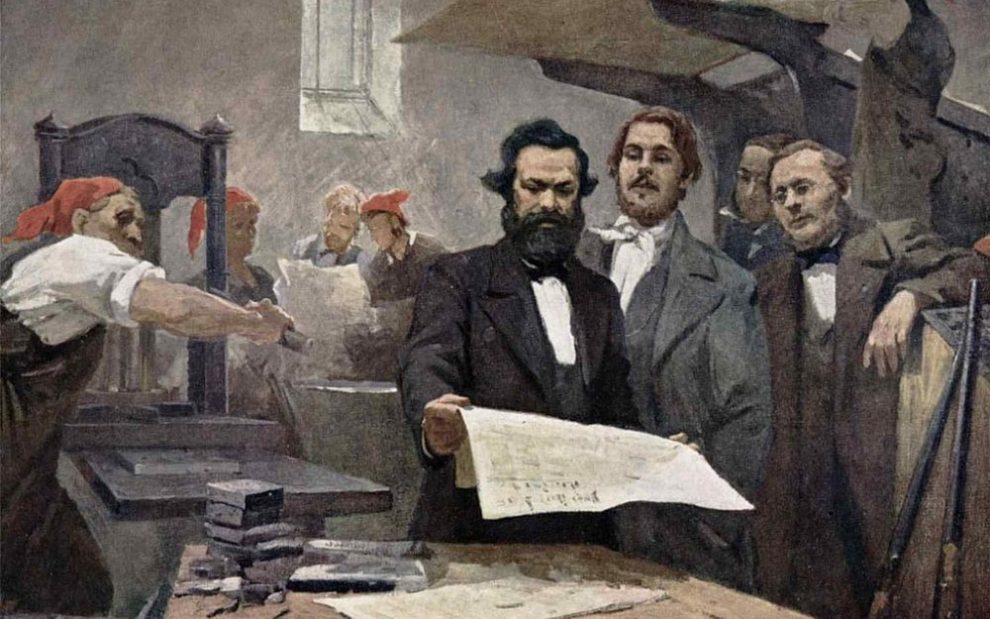

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Add comment