Some people respond with anger or outrage when they encounter a controversial work of art. Their indignation can be all the more intense if the artwork touches upon dearly held religious values. Truly, the sight of something that challenges faith can stir deep negative emotions. When the artwork is purposefully “sacrilegious,” we can certainly understand the feelings of frustration. After all, our faith does not come easily and takes effort to sustain in a pluralistic society. Faith is a gift, but it’s also a daily choice that requires thought and effort. So any purposeful or mean-spirited mockery can stir defensiveness and negative responses.

However, this invites another question: Precisely because we hold our faith so dear, should we not also be discontented and even disturbed by superficial religious art? If we truly believe in a God who loves us not only to the point of sharing our humanity but also, in the person of Jesus, to offering his life on a cross, shouldn’t surface-level depictions that make our faith seem to lack depth equally upset us?

A thoughtful engagement in our faith has inspired some great artistic masterpieces of Christianity. God has given us the gift of freedom of conscience to delve deeply into our faith and how it relates to the conditions of the world around us. This is the work not just of theologians but of artists also. Such engagement can produce images that at first may disturb our sensibilities. This may be in part due to the proliferation of so much superficiality in religious art—and, dare I say, superficiality in our religious education. However, upon a closer inspection, such works of art challenge us to reconsider the gospel, the life and message of Jesus, and Jesus’ call to his followers.

Sir John Everett Millais, Christ in the House of His Parents

At first glance, Sir John Everett Millais’ Christ in the House of His Parents seems an unlikely place to begin. After all, its tender emotions as the holy family attends to a wound in the hand of its young son; rich symbolism that foreshadows Jesus’ future; and even traditional colors of blue and red identifying Mary and her mother, Anne, make it appear to contemporary eyes as anything but controversial.

But—this is the significant point—in 1850 it was controversial! Critics took umbrage at the commonness of the depiction of the holy family and the working-class context. The details of wood chips and dirty fingernails upset art critics and viewers alike. Millais used contemporary workers as models for his holy family, and this was also “too real” for many. Even the heralded public figure Charles Dickens, so well-versed in realism and attentive to the plight of the people of his day, scathingly criticized this painting.

Seeing Jesus as truly “one of us” and sharing in our humanity proved to be a bigger challenge than expected. Why is that? Before we rush to judgment, we might pause to ask ourselves: How far have we really come? Do we really see Jesus in all people?

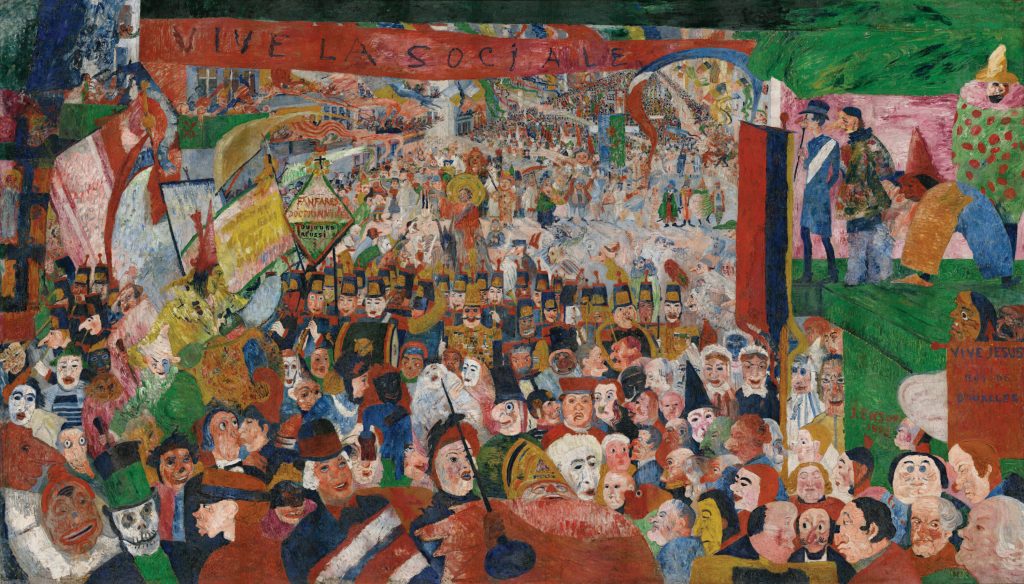

James Ensor, Christ’s Entry Into Brussels in 1889

Jump forward in time just a mere 38 years and you encounter a piece of modern art that still seems to have a visual and theological edge. If Millais challenged with a more expansive understanding of the incarnation, Ensor turned his brush against society as a whole. Ensor’s painting lifts a mirror to his contemporaries, purposefully challenging social, cultural, and religious assumptions that reveal many negative attributes.

Consider this painting in a similar vein to Fyodor Dostoevsky’s famous story “The Grand Inquisitor” in his novel The Brothers Karamazov. However, instead of Christ returning and being rejected again as in Dostoevsky’s story, Ensor’s Christ returns but is largely ignored in a society that is lost in its ways.

Ensor’s garish depictions of the people of his day speak volumes about his view of the state of things. The question is not about Jesus’ importance in salvation history. Instead, the question Ensor raises is if anyone is actually paying attention to Jesus. A cacophonous crowd of caricatured faces embellished in a nauseating color palette, Ensor’s painting stings with a question of continuing relevance: If Jesus returned, would we even pay attention?

Timothy Schmalz, Homeless Jesus

Move forward 100 years, after numerous wars, economic hardships, and far too much suffering, and we might think Jesus’ example of empathy and compassion would have taken a stronger hold in our world as an antidote to all this pain and oppression. Yet, some depictions of Jesus still have the power to make the public recoil.

In 2013 Timothy Schmalz created a sculpture of a scene all too familiar. The sculpture depicts a homeless man sleeping on a park bench. The twist is that this homeless man is Jesus. After it was installed in a park in Toronto, much public debate ensued. In fact, even after much international publicity, the same sculpture was reproduced in the Cleveland area seven years later and still stirred shock and negative reactions.

It appears Matthew 25:35 continues to have a sharp resonance: “For I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me.” Nevertheless, with a keen eye to the implications of the gospel message, Pope Francis not only appreciated this piece but commissioned a larger sculpture titled Angels Unawares for St. Peter’s Square in Vatican City. This monumental work focuses attention on the plight of migrants and refugees. Schmalz’s work has found a valued place in the church, asking important questions at the intersection of faith and life.

Janet McKenzie, Woman Offered #5

All this makes Janet McKenzie’s Woman Offered #5 so much more difficult to contemplate. We could say McKenzie’s famous painting Jesus of the People (2000) took up Millais’ mantle, showing Jesus as truly “one of us” in a contemporary context. In her powerful painting Woman Offered #5, McKenzie asks the viewer to take the next theological step.

Here McKenzie paints in her impeccably skilled manner a person both dignified and suffering. She need not add a halo or give a religious name to the woman she depicts. She simply portrays a Black woman in a cruciform position, in a stark silhouette of black and white.

Can this woman image Christ to us? Must this woman be an image of Christ for us to care? Can she not just be herself, in all her unique specificity—a particular Black woman with her particular hardships and struggles? Would that be enough to stir our hearts and minds? And what is she “offered” for, as the title of the painting proposes? Is she offered for our sins? Is she offered for our selfishness and greed? Is she offered for our failures to see all people as made “in [God’s] image, according to [God’s] likeness”? (Gen. 1:26–27).

These are portentous questions. Yet if we fail to see Christ in the plight of all people, we not only fail to understand the incarnation, but we also fail to understand the eschatological message of Matthew 25:35.

The point here is not to chastise or stir anger. Instead, it’s to lift the role of the artist as a person of faith raising challenging questions that move theology forward. The influential 20th-century theologian Edward Schillebeeckx offered a compelling idea about negative things that challenge our deeply held Christian values. He called them “negative experiences of contrast.”

Many of these paintings fall into this category. Like McKenzie’s image of a crucified Black woman, these images reveal to us something that should not be. We see an image such as this and think to ourselves, “I do not want a world where innocent people suffer!” This is the negative experience of contrast Schillebeeckx spoke of. When we see this kind of suffering and injustice, something in us intuitively rejects it and says, “This is wrong!” We look at Jesus being ignored in Ensor’s painting or the callous treatment of homelessness in relation to Schmalz’s sculpture and say, “This is wrong.”

The “contrast” holds not just a sense of what we believe shouldn’t be but also a sense of what we think ought to be instead. What we believe should surface in our minds when confronted with these challenging images. Jesus shouldn’t be lost in a crowd. Jesus shouldn’t be forced to sleep on a park bench because he has no home in this world. A Black woman shouldn’t suffer like Jesus did simply because of her race. Art can bring this to our attention in ways that words alone cannot. These are not easy images, but they are images that help us grow. And we can only hope that one day they too will seem “uncontroversial” like Millais’ depiction of the holy family.

This article also appears in the March 2023 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 88, No. 3, pages 10-15). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Woman Offered #5, Janet McKenzie, cropped. ©Janet McKenzie.

Add comment