In the online Catholic multiverse, there exists a digitally painted reimagining of the coronation of the Blessed Mother by Dani M. Jiménez, a 20-year-old artist from Costa Rica. It’s based on Diego Velázquez’s 1644 painting, in which the three persons of the Trinity crown Mary. In Jiménez’s version, God is Black and nonbinary, cloaked in rich shades of purple and red. God holds a globe, and surrounding God are ethereal, glistening clouds and galaxies. “Infinite as the Universe, not unlike Their love for us,” reads the caption of the piece.

Under the brand name “& her saints,” Jiménez paints digital icons and re-creations of traditional religious paintings and posts them on her Instagram account. She also has a blog and an Etsy shop where she sells prints of her work.

& her saints is one of hundreds of independent Catholic brands that sell art online and on social media. Some of these brands produce goods on a mass scale and sell them. Others make goods with specific aesthetics, such as Blessed is She—which sells items like planners, jewelry, posters, and candles with a feminine, minimalist design—or Rugged Rosaries, which has a distinctively masculine aesthetic and sells marketed “combat rosaries” with a “gunmetal finish.” Then there are independent artists, such as Jiménez, selling their work.

“Catholicism is a sacramental tradition,” says David Cloutier, who teaches moral theology at the Catholic University of America and specializes in environmental and economic issues related to consumerism. “We believe that we meet God through the material world, not apart from it. Miraculous medals, the rosary, the fact that we use material objects to strengthen our faith—all are part of what it means to be Catholic.”

The material objects that strengthen faith have a long history in Catholicism. In the Middle Ages there were intricately carved statues of the Virgin Mary and golden paintings of icons, but only churches or members of the elite were able to own that art. The folk objects most people had were handmade, such as a St. Brigid’s cross woven with fronds from flowers or wheat.

In the early 19th century, the rise of industrialization gave way to a proliferation of goods on a mass scale, which allowed the average person to afford religious pieces, says religion scholar Colleen McDannell, who teaches religious studies and history at the University of Utah. These items were often sold in local Catholic bookstores.

Today, buying and selling are mostly done online, which makes it “very fragmentary and very diverse, and there are no gatekeepers,” McDannell says. The aesthetics of products being sold online are as wide and varied as those for any other non-religious product.

Religious aesthetics are influenced by popular culture, and the history of Catholicism reflects this. In the 1800s, Baroque-style churches were lavish and saturated with images and art, following trends of Victorian maximalism. Then, in the 1960s, following the Second Vatican Council, minimalism emerged as an aesthetic and philosophy in the art and architecture world. The church caught on as all its own reforms were taking place, and rococo churches were replaced with simple worship spaces with clean walls. They took on this simplified look so people would focus on what was happening at the altar, McDannell says. But now, in 2022, visual and interior excess are replacing minimalism once again.

“In spaces controlled by the church, those images get frozen,” McDannell says. “On social media, and anything that’s controlled by laypeople, that process of change is really fast.”

Aesthetics and identity

One of the hallmarks of a consumer society, Cloutier says, is that “goods are marketed, not simply for their function but rather as an expression of our identity. [For example], I decorate my house in a particular way, not just for functional reasons, but because it’s somehow expressing who I am.”

The aesthetics of religiously themed objects points not only to religious identity but to a particular cultural, generational, or aesthetic identity. “Whether the clearly masculine Rugged Rosaries or strongly feminine Blessed is She site, in both cases it’s clear that it’s not just that you want a cross to put on your wall because you’re Catholic, but you want a cross that looks a certain way, or a rosary that looks a certain way, because it’s expressing something about your identity,” says Cloutier.

The Millennial aesthetic that has taken over social media marketing since the mid-2010s is pastel and minimalist: products and ads created in pinks and greens and infographics in hand-lettered calligraphy with neat, curvy shapes and designs. Brands in the Catholic world have adopted this aesthetic: One, West Coast Catholic, sells minimalist gold jewelry and simple rosaries with wooden or pastel stone beads and a thin crucifix.

Be A Heart employs this simpler aesthetic as well. The brand sells items such as sewn Mary dolls and softly patterned playmats for kids as well as journals and wall art with hand-lettered quotes. Erica Tighe Campbell, the artist behind Be A Heart, says, “A lot of my aesthetic choices really have come from looking at what is happening around me: What I was seeing in Los Angeles, the different trends, what people were wearing, what people were putting in their homes, the trends of hand lettering . . . and thinking about different ways that I could represent my faith life in that.”

Campbell hopes that with her brand “you wouldn’t necessarily know that it’s a faith-based product because it doesn’t look like what we’re so used to seeing, especially in Catholic goods,” she says. “But it looks like the other thing that I’m buying at a shop, and then it has something that’s slightly more elevated.”

In brands that cater to men, many take on battle and war themes, such as Sanctus Co., which markets itself as “uniquely masculine goods for Catholic men” with an emphasis on “spiritual warfare.” It is minimalist, using a solely gold and dark gray color scheme, with thin-lined images such as of swords and the keys of St. Peter on the Vatican flag. (U.S. Catholic reached out to Sanctus Co. and Rugged Rosaries for comment, but they did not reply.)

“These products are attempting to connect your religious identity with some other kind of identity expression,” Cloutier says. This doesn’t always have to be worrisome: For example, for Latino/a Catholics, he says, “There are all sorts of religiously themed goods that are also clearly expressive of Hispanic identity. No one is going to say, ‘You have Our Lady of Guadalupe on your wall just because you want to express some kind of identity.’ Well, you are actually expressing your identity, but it seems authentic to us in a way that we’re worried about some of the other ones [not being].”

Subversive artistry

In Jiménez’s art, darkness has a subversive splendor. “I really like dark,” she says. “I want to bring attention to this duality that’s been pushed throughout history that darkness is evil and God is light, and therefore that includes people of color. Aesthetically, I like darker images. I feel more comforted in that, and I do find God. It brings that comfort of being cloaked in something.”

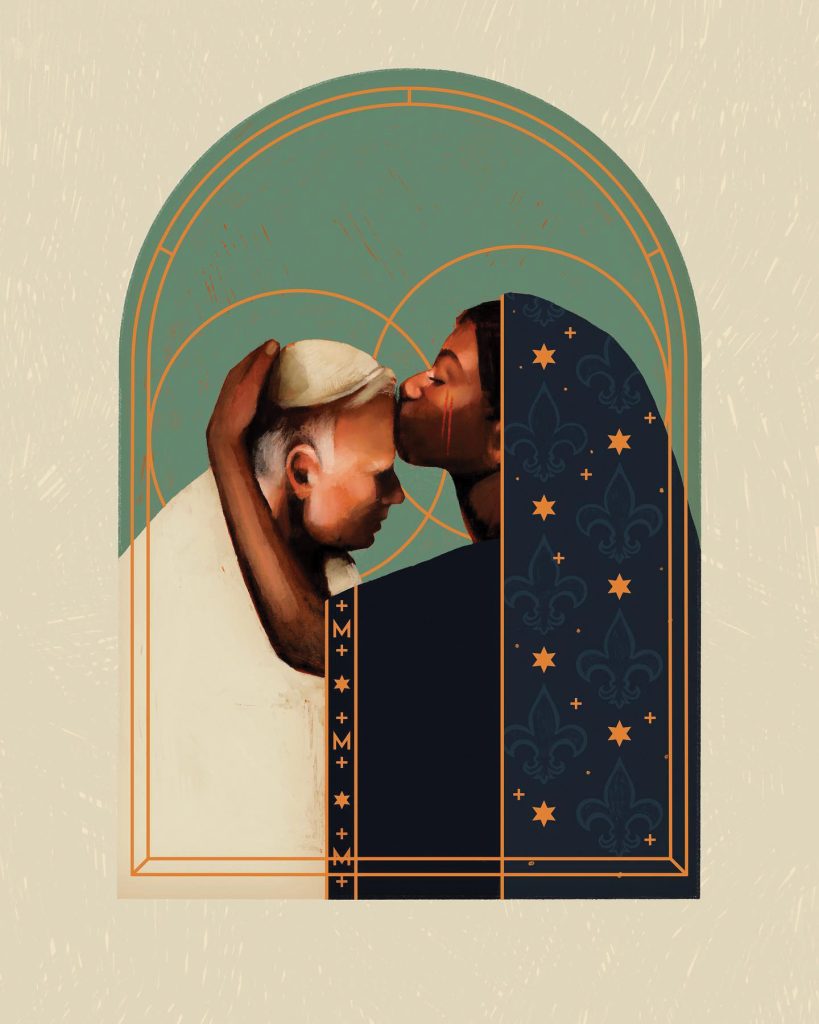

Ryan McQuade, a visual designer and illustrator in Nashville, is also drawn to the dark. His artwork has a “grungier, punkier aesthetic [that] I think works really well with Catholicism,” he says.

“The punk and grunge subculture are anti-authoritarian, rebelling against oppressive systems, [which is] something that I feel is inherent in Catholicism,” McQuade says. “That aesthetic actually feels very spiritual to me.”

One of McQuade’s pieces is an AI-generated grunge rendering of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. The word sacred fills the lower half of the screen in a clawlike font reminiscent of a Def Leppard band T-shirt, a crown of barbed-wire thorns choking the silver metal heart. In another piece, a statue of Mary is breaking open a chain-link fence, neon yellow sizzling on the gray stone. “We’re not free until we’re all free” is scribbled into the corner, in lettering that looks like it may have been carved into a subway seat with a key or pocketknife.

McQuade also does branding work, such as curriculum design for Life Teen, promotional material for Steubenville youth conferences, and book covers for Pauline Books and Media. He posts his artwork on his Instagram account @ryanmcq, which he says is followed mostly by “disaffiliated Catholics, deconstructing Catholics, and queer Catholics.”

McQuade created “Our Lady of the Closeted” because he “didn’t see any artwork that had anything to say about the queer Christian experience of Mary,” he says. In it, Mary—with closed eyes and a longing, grieved look on her face—is leaning against a closed door, a sword in her chest. “If you talk to queer Catholics who have a strong devotion to Mary, many see that image and recognize, ‘That’s totally who Mary was to me at that time of my life or is to me right now,’ ” he says.

McQuade says that he sees a “real demand for more marginalized, nuanced viewpoints of Catholicism because we just don’t have a lot of that, and what we do have doesn’t tend to get put in churches.”

Many Gen Z Catholics like traditional Catholic aesthetics and are politically progressive, says Kassidy Beane, who runs the TikTok account @the_hippiecatholic.

Her account’s aesthetics can be summed up in one of her favorite niche music genres: Catholic psychedelic synth folk. Beane blends the “hippie stuff”—flower crowns, tie-dye, bright bandanas, and daisies—with Baroque and medieval Catholicism. “I wanted to be able to preserve and innovate, adding to a preexisting tradition, because that’s what Catholicism is, really,” she says.

Online, Catholicism has ironically become its own aesthetic. “People who might not be practicing Catholics, they’ll be embracing the aesthetics of Catholicism,” Beane says. “I still tell people to be careful because we don’t want our religion to just be an aesthetic either.”

Gen Z, Beane says, is a “generation that does not know what to believe. Unlike Millennials, who are kind of cynical, Gen Z believes in something but they don’t know what that something is.”

Augustine Calmet, a 22-year-old Armenian Catholic who runs the TikTok account @dom.calmet, began to incorporate more Catholic theology and aesthetics into their posts when they started converting to Catholicism.

They took their name from Antoine Augustin Calmet, an 18th-century French Benedictine monk who documented and studied vampires and the occult. They first learned about the monk through a song about vampires that included a mistranslated piece of his work. When Calmet converted, they took up his name.

Calmet’s fashion is monastic and mythical—long robes and veils inspired by monastic habits, their Armenian heritage, as well as Dungeons & Dragons and the mystical landscapes of video games. They can sometimes be seen wearing elf ears under their veil, and they wear only religious jewelry: a crucifix necklace, rings with icons, or saint medals. “I feel older than my priest, and he is a [Baby] Boomer,” they say.

Augustinecore, one of Calmet’s videos, is a moving gallery of blurry images: candles, Gothic cathedrals, a field of grass, sun spilling from a church dome into an empty sanctuary, a Baroque altar, a butterfly.

McQuade finds the Gen Z aesthetic of “I’m not trying but I’m trying” refreshing, especially when Catholicism is factored in.

“It’s bad photos, and the fashion is camp and crazy,” he says. “It’s this rebelling against Millennials trying really hard. I think it’s really cool to see [Gen Z Catholics] not taking it so seriously. I think Millennials reacted very seriously to Catholicism, and you got things like Catholic Answers and all this apologetics stuff going crazy. [With] Gen Z, it’s, ‘We’re just enjoying our faith and our religion like we are enjoying other things.’ ”

“[In] my room, I have my cross, my gallery wall, all my paintings, some art above my bed, rosaries hanging everywhere,” Jiménez says. “I love reminders, walking into my room and being like, there’s God, remember to give thanks. There’s a saint, ask for their intercession.”

Beane believes the buying and selling of Catholic arts and goods from independent brands online is a “way for laypeople to take back control in a meaningful way and stand up against clericalism,” she says. “You’re allowing people to have a platform and to freely speak without being hindered by a bishop or priest or someone else who might not want these things to be talked about or depicted in certain ways.”

‘We are not walking wallets’

Even though “Catholics love stuff,” Beane says, Catholicism teaches that every person has inherent dignity, which means it’s unethical to commodify religion or use human beings as money to be had.

When evaluating consumption, Cloutier suggests that “Catholics should shift from thinking about identity expression variables to thinking about real relationships that are formed through the exchange of buying and selling, and asking, ‘How is all of this helping everybody’s dignity?’ ”

“When we [talk about] artists and directly connect with artists, I think we’re talking about something different than an online store that sells items that they are sourcing from some big manufacturer,” he says. “How are the workers treated, and do they find dignity in their labor? Are environmental resources being used well or badly in these items?”

At the heart of the gospel is a “radically different worldview” than the one of consumption and commodification we live in, McQuade says. “Jesus talks more about money than hell. We are not walking wallets. I think because the rest of our culture says you can’t even exist without paying somebody to exist, then we have to radically oppose that. Otherwise I don’t think we’re doing anything special.”

Because Catholics find meaning in religious goods, it can be tempting to feel as though “we are participating our way into Catholicism by buying into Catholicism,” McQuade says.

“There’s a lot of [Catholic] apps or people online that tell you, ‘You need this [product] to continue your faith,’ ” Jiménez says. “I don’t think that’s moral. You don’t need art to be connected to the divine—it’s a plus.”

“We should always be resisting the over-consumption and capitalization of Catholicism,” McQuade says. On another hand, supporting Catholic artists, “who are going to bring their full experience of faith to pieces,” remains important, he adds.

Artists “critique the culture [by] showing you exactly who you are,” he says. “I would love to see 3-D modeling, AI-generated art, and digital paintings in Catholic churches, because I think that’s the innovative work. My hope is that digital artwork would be looked at the same way as a traditional oil painting. I think that’s evangelical—it’s really meeting the moment. It’s not like we’re riding the wave of technology, but we’re actually at the heart of envisioning it.”

The ‘sacred place inside yourself’

The reality of the internet is that it is a commercial space “where you are constantly being advertised to,” McQuade says. “It is important that as you are engaging in a digital space, you realize you are still a customer in those spaces. I think maybe the only places that are left sacred are yourself and prayer.”

Retaining a sacred place inside yourself where “you are allowed to just exist” is a way to remain discerning through the noise of ads. “A lot of people will say, ‘Just stay off [social media] altogether,’ ” McQuade says. “But I don’t think that we can exist in 2022 and not be on social media to some extent.”

If consumption and aesthetics “distract from the basic responsibilities of discipleship and the centrality of the church’s liturgy,” Cloutier says, then they become dangerous. “Those are the two things that ought to be the center of Catholic identity, not the consumer choices.”

Calmet says people find their account and expect them to be a certain way politically, and they receive some hate for that. “My life history taught me that no human in this world can be allowed deep into [my faith],” they say. “The only people that are allowed to do that are saints.”

At the center of one’s being, Thomas Merton writes, there exists a “nothingness,” a point of “pure truth,” a “spark which belongs entirely to God.” This breath of God in each person resists its own commodification and upholds its own dignity. To be in touch with that spark through authentic prayer and embodied faith practice are the roots of Catholicism—everything else, like Jiménez says, is a plus.

“As Christians, we have to be critical even of [online] spaces, and say, ‘I have to build a time where I’m not being advertised to,’ ” McQuade says. “Because I’m not a product. I’m a person, and I have to cultivate this spirituality.”

This article also appears in the December 2022 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 87, No. 12, pages 26-30). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Header image: Unsplash/Marco Ceschi

Add comment