Corita Kent, through her art and words, gave me two life-giving lessons this year: love the moment, and love the darkness.

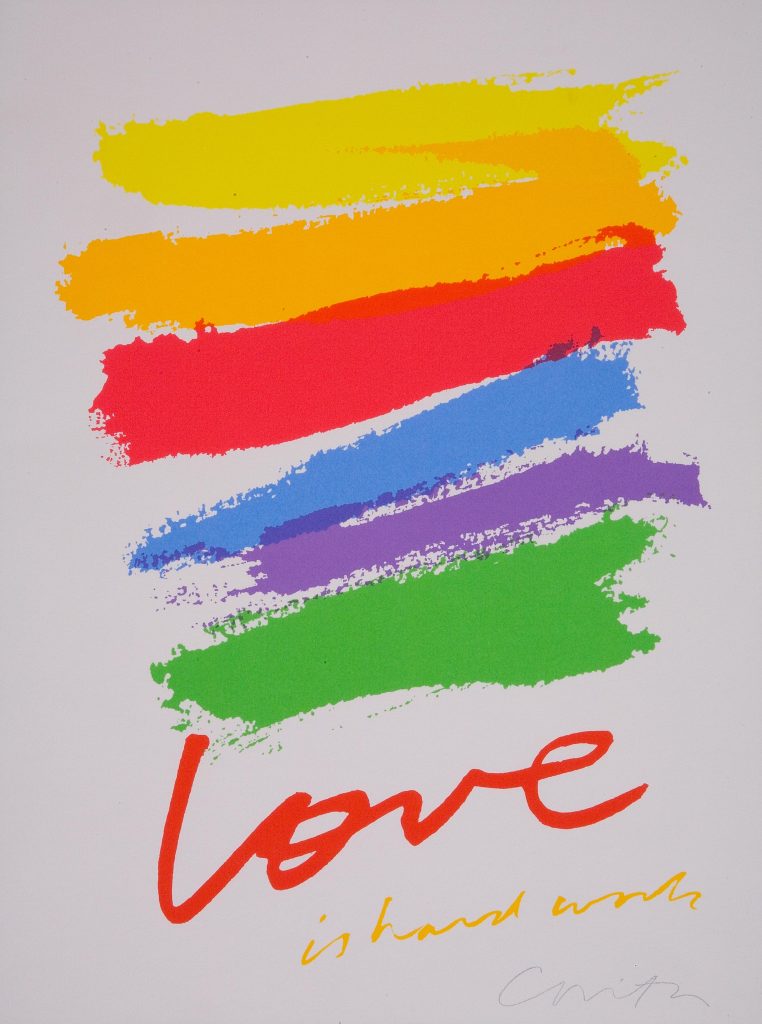

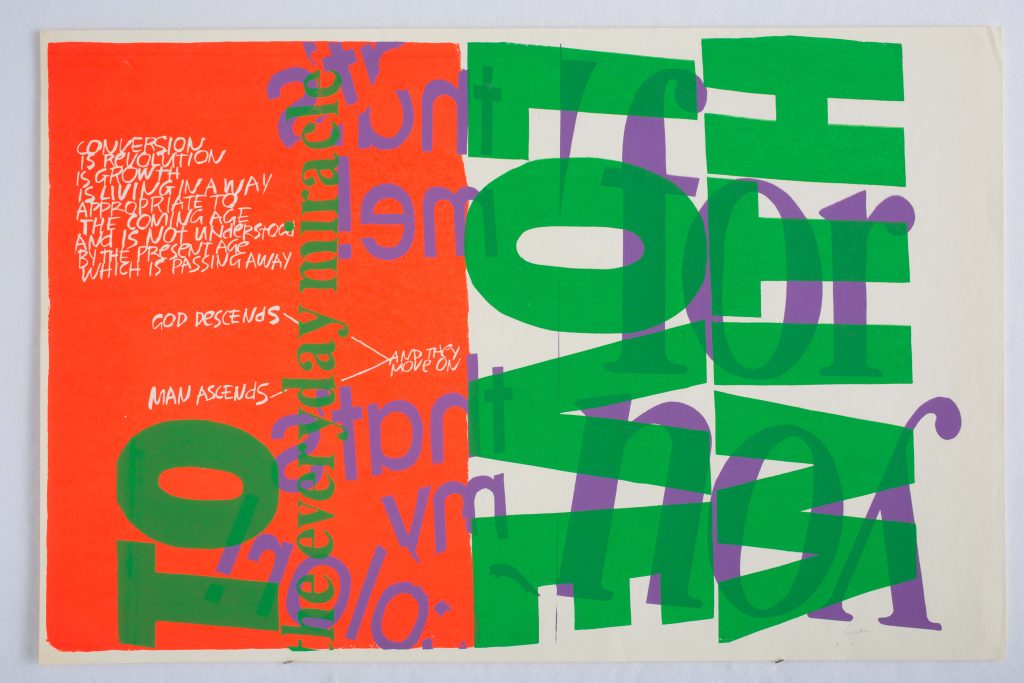

Spending time with the works of Corita—the “pop art nun” who taught art in Hollywood in the 1960s and created colorful serigraphs (silk-screen prints) about social justice, faith, and human longing—gave me solace and inspiration in a year of darkness. The themes and quotations in her art helped me ask questions about my role as an artist and young person in this world of injustice and sorrow. How do I create in and from the darkness in myself and around me? How do I live ethically and authentically? How do I love well?

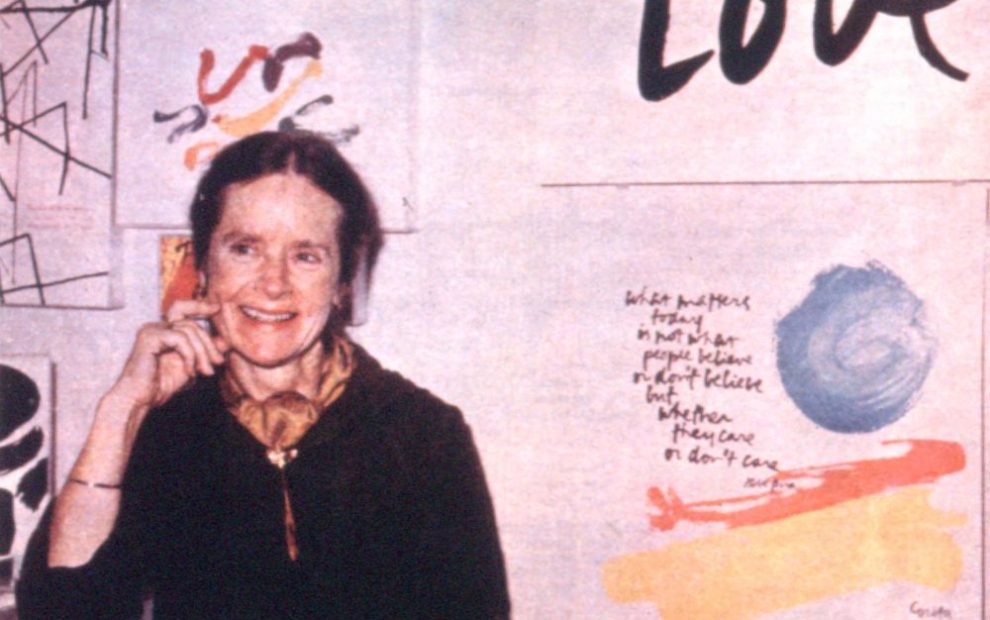

Known as the “joyous revolutionary,” Kent “care[d] about it all.” She was born in 1918, and at age 18 joined the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary. She taught at Immaculate Heart College in Los Angeles and became head of the art department in 1964.

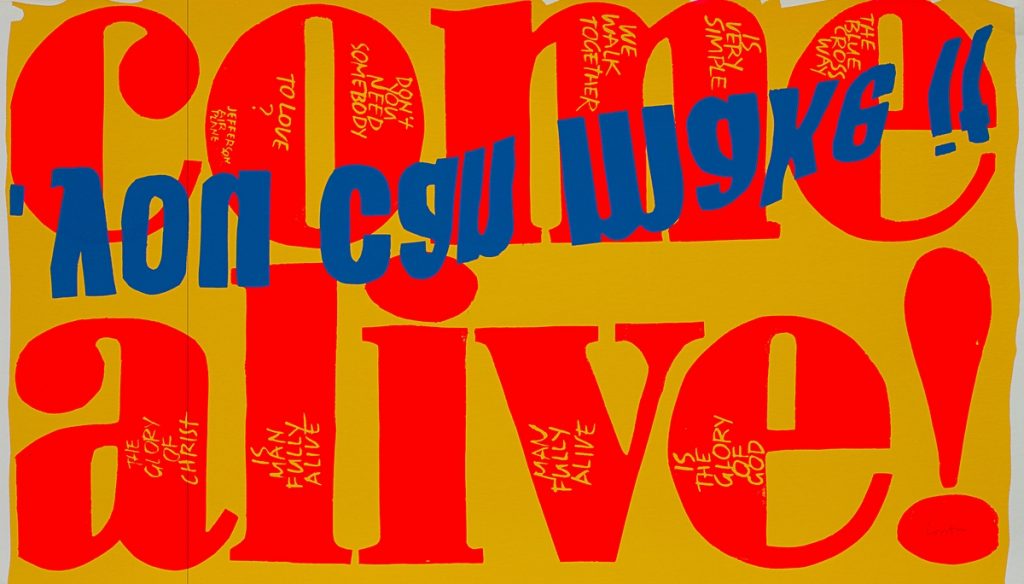

“Poets and artists notice the common place, how good it is,” she said. Like the words say in her pink, block-lettered print “the cry that will be heard,” she wanted her students and city and church to “give a damn.” Taking popular slogans, advertisements, song lyrics, spiritual writings, and grocery signs, she responded to the injustice, racism, poverty, and war happening in her 1960s Los Angeles through colorful and thought-provoking silk screens.

I first learned about Kent during my freshman year of college in San Diego in 2016. The bright California-ness of her serigraphs, coupled with her love of God and neighbor, resonated with me as I wrestled with my faith and identity in the exciting cities of the West Coast. I hung postcards of her art in my dorm room. I visited the Corita Art Center in Los Angeles and interviewed some of her former students and friends.

The more I discovered about Kent, the more she felt like a mentor, challenging me to use my creative skills for good, to be bold, borrow widely, and give everything a chance to surprise and inspire me. With her help, I learned to channel my longing for justice and truth into creative participation with my surroundings. To “create is to relate,” as Kent said, in this neon world with all its cracks and darkness.

Swaths of lemon yellow and electric purple make up an abstract flower in one of her serigraphs. “Love the moment,” it says, “and the energy of that moment will spread beyond all boundaries.”

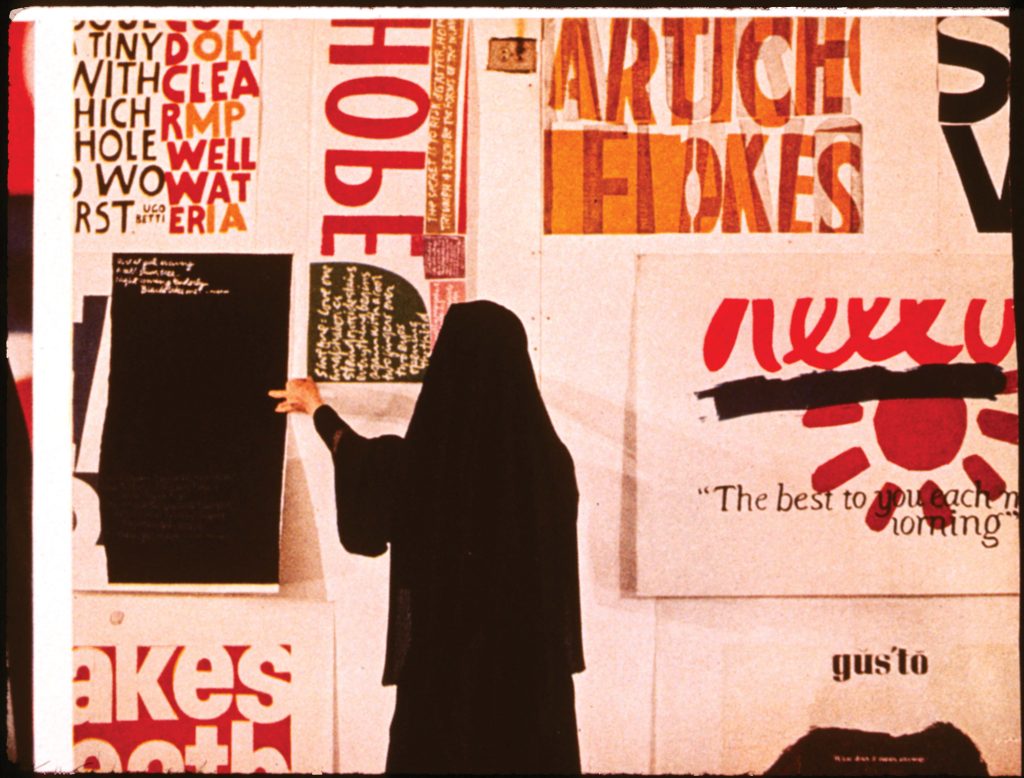

Kent’s love of the moment was, and still is, contagious. She organized Mary’s Day, a celebratory procession for her students and community, to make Mary “more relevant to our time—to dust off the habitual and update the content and form.” In photographs, nuns in their long black habits and students in costume carry eclectic banners of grocery signs with streamers and balloons, some of them playing guitar and drums.

“All we are doing is acting out this incarnation,” reads the bright red lettering in her 1968 print “v is for vibrations.” “So it’s really that every moment’s important, and just to dig it all, and by digging it all you’re naturally harmonizing with it, which is a form of appreciation of God.”

Kent continued to dig and harmonize and appreciate, even while receiving backlash from Cardinal James Francis McIntyre, the archbishop of Los Angeles at the time. The public spotlight and heaviness of existence took a toll on her. In 1968 she left her order and moved to Boston to keep making her art. “I make very happy things when I am very, very depressed,” she said. “I think that I make them to help me.”

When the pain of suffering, loneliness, and confusion is overwhelming, Kent’s artwork reminds me to ground myself in the moment, in real-life colors and smells and sounds, and start from there. “It seems that my only way of understanding words is to say that prayer is everything,” Kent writes. “Breathing, helping, wanting, taking courage from someone, giving courage to someone, needing desperately, fearing.” To notice my surroundings, to smile at the sun, to write one true sentence—these little moments are incarnational because they give me hope to keep going, to keep praying with all my breaths and fears.

“The hard times, too, are part of the creative process; for example when I can’t sleep at night or lose the meaning of what it’s all about,” Kent writes in Learning by Heart (Bantam). “It can be . . . a dirty, collecting time when I sharpen pencils or clear work space, but we know that somehow these things are necessary. . . . If you can think of the most difficult moments of your life and you can feel those times to be part of the creative process, though very painful (I think it must hurt the trees to lose all their beautiful leaves), then that is, for me, really working, really creating, it just isn’t the finished product.”

Her watercolor print “Spring from Winter” features a gentle bursting flower in muted rose and baby blue. At the bottom left, “spring from winter” is scribbled in her signature handwriting. I have a postcard of this print taped on my wall, and I often pray with it as I try to make sense of the winter of my early 20s, of the constant transitions, of having so much empathy for the world and not knowing what to do with it. Even in the heartache of it all, this reminder—Kent’s trust—in “spring from winter” blooms truthfully in me.

“Love the darkness,” reads neon blue lettering in her serigraph “out of the darkness,” beneath fiery streaks of magenta. “Out of the darkness of one moment grows the light of another moment, perhaps in some distant time. . . . Love the darkness.”

Kent died in 1986. Her work continues to inspire artists, activists, and spiritual seekers, reminding us to love what is real, delight in the ordinary, and “dig it all.” My longing for what is greater than myself (is it God?) is a colorful crack in the dark, a magnetic pull that makes me write, makes me create, makes me ache for a better world. “Flowers grow out of the dark moments,” says her glowing orange, red, and yellow serigraph “flowers grow.” The dark moments are where life comes from.

Toward the end of Kent’s life, she worked on a series of books with the poet Joseph Pintauro. “To believe in God,” one of them says, “is to get so attached to everything that it can’t give you up.”

Like Kent, may we love each boundary-bending moment—the here and now of our incarnate lives—in this dark, sticky, spring-and-winter world that can’t give us up.

This article also appears in the July 2022 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 87, No. 7, pages 43-44). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Corita with serigraphs, c. 1960. Image courtesy of the Corita Art Center, Los Angeles, corita.org.

Add comment