A search of #catholictattoo on Instagram yields thousands of results. Our Lady of Sorrows cries juicy tears on biceps; rosaries snake down forearms and wrists; sacred hearts in full color burn on chests; and Virgin Marys stomp snakes from reddened, puffy, freshly inked skin. #religioustattoos yields tens of thousands more images, many of them Catholic. Catholic imagery seems increasingly mobile and personalized, made newly portable by being inked into the skin.

In 2018 at a meeting with young Catholics before the Synod of Bishops on Young People, a Ukrainian seminarian asked Pope Francis about tattoos and how to discern the “good” parts of modern culture. “Don’t be afraid of tattoos,” Pope Francis instructed, because they can be starting points for priests to connect with the young. He continued on to say that “tattoos signify membership in a community” and can open up conversations about belonging.

While Pope Francis encourages new openness toward contemporary body modifications, there is, in fact, a much longer history to Catholic tattoos. For centuries, Catholics have rendered their religious journeys, their devotions, and their communal identities permanent in flesh. Today’s burgeoning tattoo culture reflects the history of Catholic votives, sacramentals, and pilgrimages and the many physical ways Catholics have entered into relationships with sacred places, the saints, and one another.

Looking at the rich tradition of Catholic sacramentals, objects, and gestures excites “pious dispositions,” according to the Oxford Encyclopedia of the Reformation. In her book Material Christianity (Yale University Press), Colleen McDannell writes that they “serve as a doorway between the sacred and secular worlds”: Both these descriptions offer us insight into tattoos. These objects, no matter how precious or mundane in substance, invite users and wearers into relationships beyond the medium in which they are made.

While the church has traditionally defined sacramentals as objects that have been officially blessed and authorized, Catholics have understood many things—regardless of their official status—to be holy. For Catholics, there is rich potential for the sacred throughout the material world and in daily life. Little objects made of gold, plastic, wood, and wool, when worn close to the skin or on the body, have helped Catholics inhabit and feel their religious identities.

Carrying your grandmother’s rosary, keeping your keys together with an Our Lady of Guadalupe keychain, tucking a prayer card into your wallet, wearing a scapular under your shirt, or keeping a little saint on your dashboard are all examples of objects and actions that inspire feelings of comfort, assurance, and protection. These physical reminders are channels of divine and human love.

Increasingly, tattoos stand in for these more traditional Catholic objects and practices as lifelong and durable signs of devotion. However, tattoos also have a much longer Catholic history.

Historically, the Franciscans were quite the promoters of tattoos in their role as caretakers of the Holy Land. As early as the 16th century, Holy Land pilgrims included getting tattooed on their itineraries. Along with visiting the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and walking on the Via Dolorosa, pilgrims made time to have their skin engraved. According to historian Katherine Dauge-Roth, Franciscans “invited tattoo artists into their monasteries to perform their services or allowed them to set up shop on the grounds of shrines maintained by the order.”

Much like today’s flash tattoos (readily available, predrawn designs), artisans in the Holy Land offered a catalogue of “pilgrim flash,” engraved woodblocks that offered iconography such as the Jerusalem cross or the names of Jesus and Mary. There is also evidence that pilgrims got custom tattoos. From maps and architectural drawings of holy sites to images of the crucifixion, tattoos rendered permanent the otherwise fleeting experience of pilgrimage.

At the Holy House of Loreto in Italy, also a Franciscan shrine, tattoos were part of the pilgrimage experience. Pilgrims could choose from emblems of the passion, the Blessed Sacrament, rosaries, saints such as Clare and Francis of Assisi, angels, crucifixes, and various Madonnas.

Holy Land tattoo designs began as woodblocks. These were coated with charcoal and stamped on the skin, usually on the forearm, to create a stencil. The artist would dip needles into a mixture of gunpowder and ox bile. While holding the skin taut, they would outline the design with needle pricks, depositing the ink with each puncture. The skin would then be rubbed with pigmented powder, further depositing color into the flesh before the artist washed the site with wine and wrapped it for healing.

The process was similar in Loreto, where artists would rub indigo ink into the punctures in the skin. In both the Holy Land and Loreto, blue tattoos were the final product. Some art historians liken the bloody affair of getting tattooed to receiving the stigmata—wounding that leaves permanent marks connecting the human to the divine. They cite both the placement of tattoos on the wrist and lower forearm and the fact that people typically got tattoos during Eastertime.

Tattoos rendered the Holy Land portable and intimate, no longer a place “out there” but a place integrated into the very body of the devotee who had trodden its landscape. These tattoos were small personal sacrifices and souvenirs of a religious journey, but they also integrated wearers into a collective Christian body. With these tattoos the sacred and saintly became perpetually accessible.

Catholics have always understood devotional relationships to be mutual, and saints have long been our conversation partners, confidantes, and powerful friends. As Catholics have reached out to the saints in times of need, they have also made promises and offered symbolic parts of themselves to these holy helpers in the form of ex-votos (the term comes from the Latin ex voto suscepto, or “from the vow made”).

Especially popular in the Mediterranean region and Latin America, ex-votos have taken the form of legs, arms, hearts, eyes, and other body parts stamped in tin, brass, and silver. These fragmented body parts decorate shrines and act as testimonies of faith and healing. In Mexican churches these small brass offerings are called milagros or milagritos, or “little miracles.” Milagros are often pinned on the garments of a saint’s statue along with photos, locks of hair, and handwritten notes.

In giving these symbolic pieces of themselves, devotees materialize their hopes and their gratitude to saints. They personalize shrines and church spaces by leaving traces of their prayers and vows fulfilled. These visible, touchable, giveable objects make the private intimacies of prayer public, and each one holds an “experiential narrative” about a saint’s intercession.

As art historian Ittai Weinryb argues, “The votive offering serves as a perpetual statement of the relationship between the body of the devotee and the act of offering.” And what is more perpetual than a tattoo?

Like votives, tattoos allow the body itself, rather than the body-symbolized, to become the channel of gratitude—the skin becomes the medium of the votive. While votive offerings have often been melted down, burned, or done away with to make space for new offerings in shrines, etching a saint permanently into flesh allows a saint to be carried forever, a perpetual signal of the connection between the human and the divine.

Today, even priests have tattoos that speak to their vocation and their place in the Catholic community. Jesuit Father Patrick Gilger, a priest and sociologist, has a tattoo on his forearm of Jesus as a mother pelican, a eucharistic image of a pelican piercing her breast with her own beak to produce blood droplets that nourish her chicks.

For Gilger, this image exemplifies what it means to be a Catholic priest: “In my own understanding and in my prayer, what that really amounts to is learning how to live self-sacrificial love that’s not self-focused, not self-concerned,” he says.

While tattoos are deeply personal, Gilger says they are also “publicly visible symbols,” and his tattoo is a powerful, visual way of “speaking in public about where [his] commitments lie.” As for the pain and intense physical experience of getting tattooed, Gilger prayed through it and found that getting inked can be a “moment of self-giving.”

With their tattoos, lay and clerical Catholics alike inhabit and develop their personal religious identities and their devotional and communal commitments. Tattoos can also be conversation starters and openings for engagement. According to Gilger, tattoos can be a way for Catholics to inhabit and develop their spiritual gifts. Getting inked can be a “bearing out, deepening, and solidifying of a particular gift,” he says, and if a tattoo “remains within the logic of the gift, then I think this is something to be excited about and supported.”

This article also appears in the August 2022 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 87, No. 8, pages 31-35). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

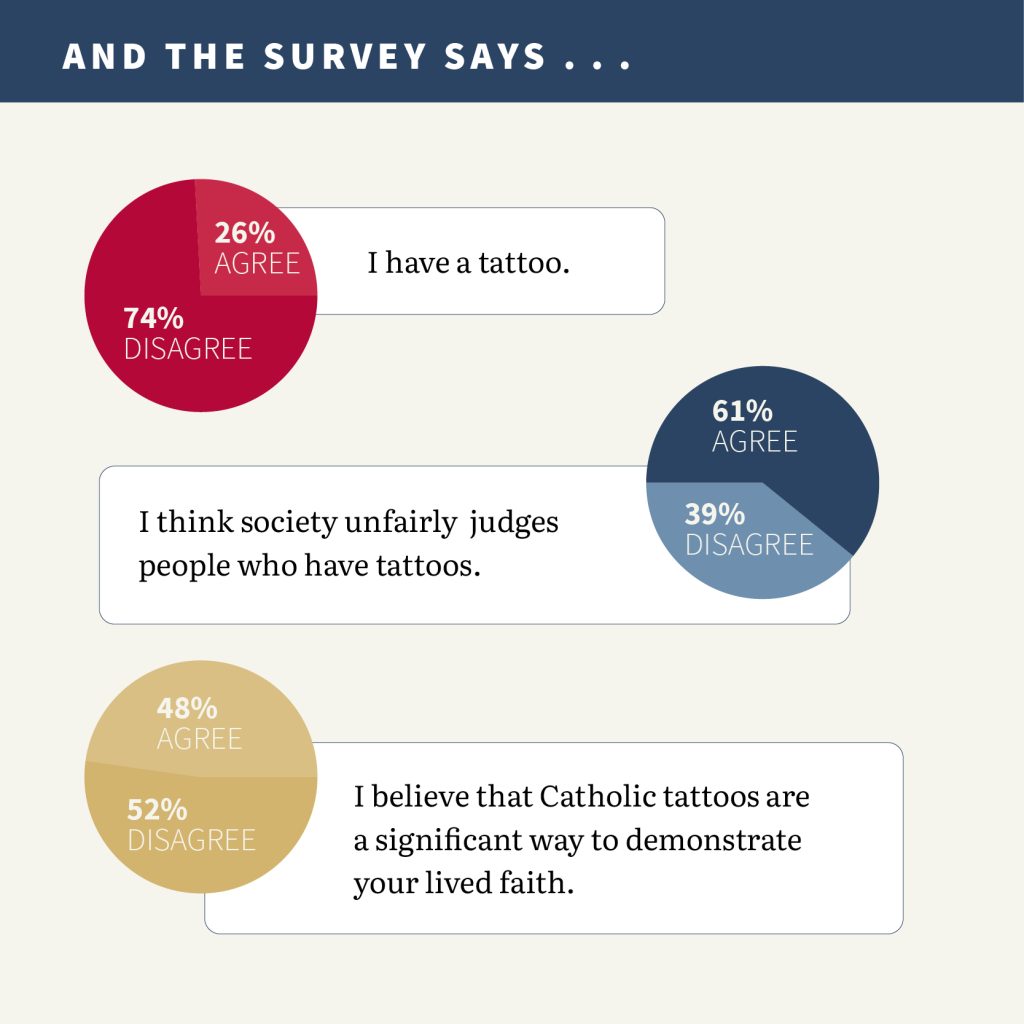

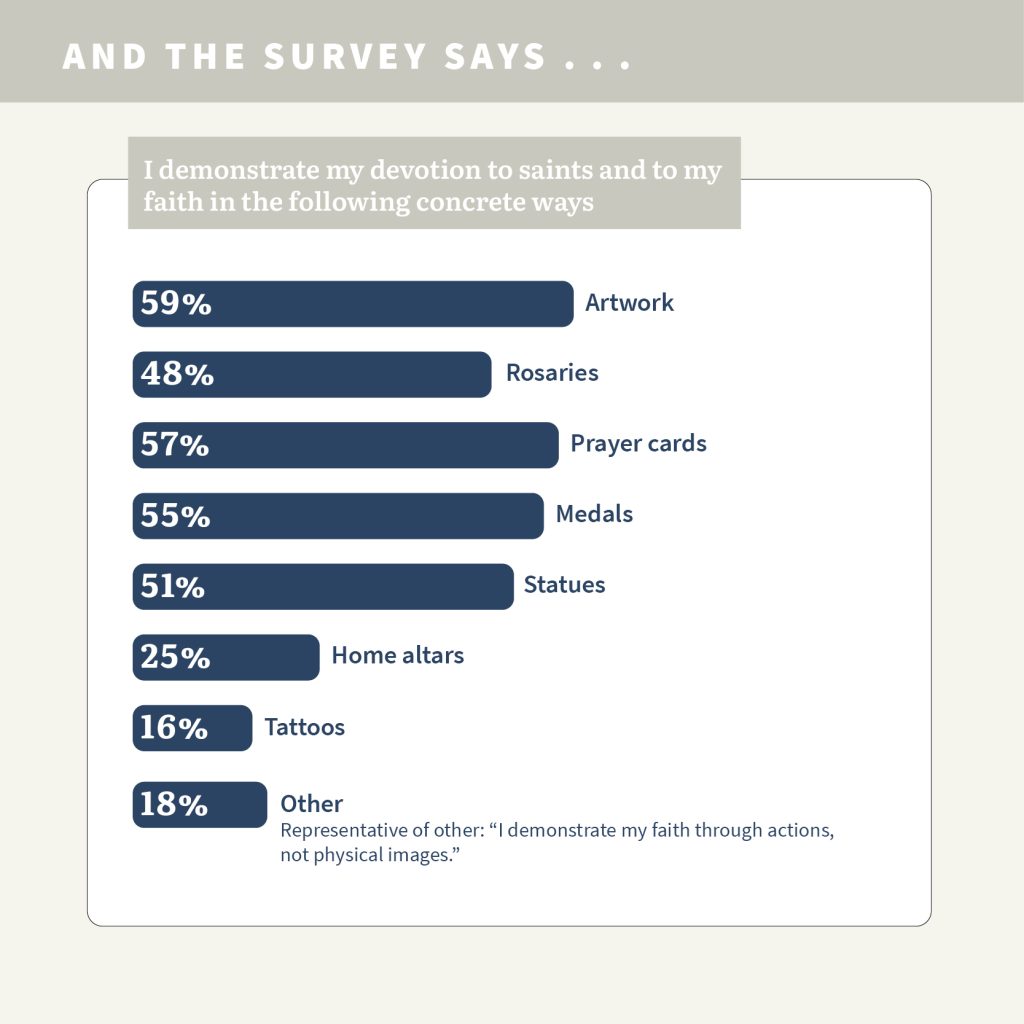

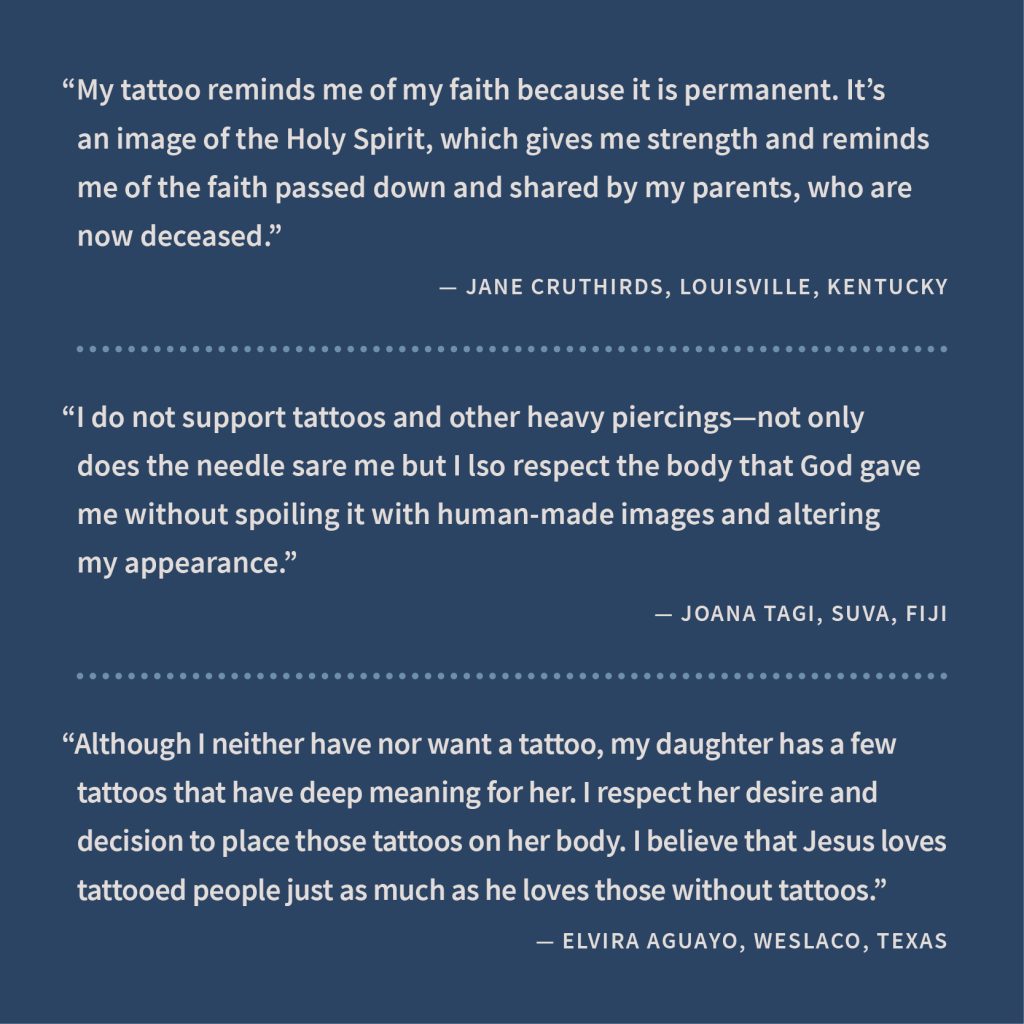

Survey results are based on responses from 94 uscatholic.org visitors. Sounding Board is one person’s take on a many-sided subject and does not necessarily reflect the opinions of U.S. Catholic, its editors, or the Claretians.

Add comment