A preacher’s job is harder in the 21st-century United States than in many other places and times. Imagine attending a liturgy and hearing the gospel preached in the Romanesque or Gothic churches of Europe when they were newly built. Those churches stood as the geographical heart and center of communities. Imagine a medieval villager’s sense of amazement while attending a liturgy. It must have been dazzling compared to daily life.

Today, our context is wildly different. Where pulpit preaching at Mass was once practically the only game in town, contemporary Mass-goers are inundated with sensory input and messaging in our postmodern world. We have multiple streams of content vying for our attention 24 hours a day: a proliferation of podcasts, programs, films, and other resources on every topic possible, including spiritual and religious content. We are swimming in far more information than our human brains can process meaningfully. Whereas the imagined European villager might have been dazzled by the majesty of the liturgy 1,000 years ago, in large part because of its difference from the monotony of daily life, we live in a state of constant overstimulation. When everything is dazzling, nothing is. How can a sole preacher hope to compete and break through the noise?

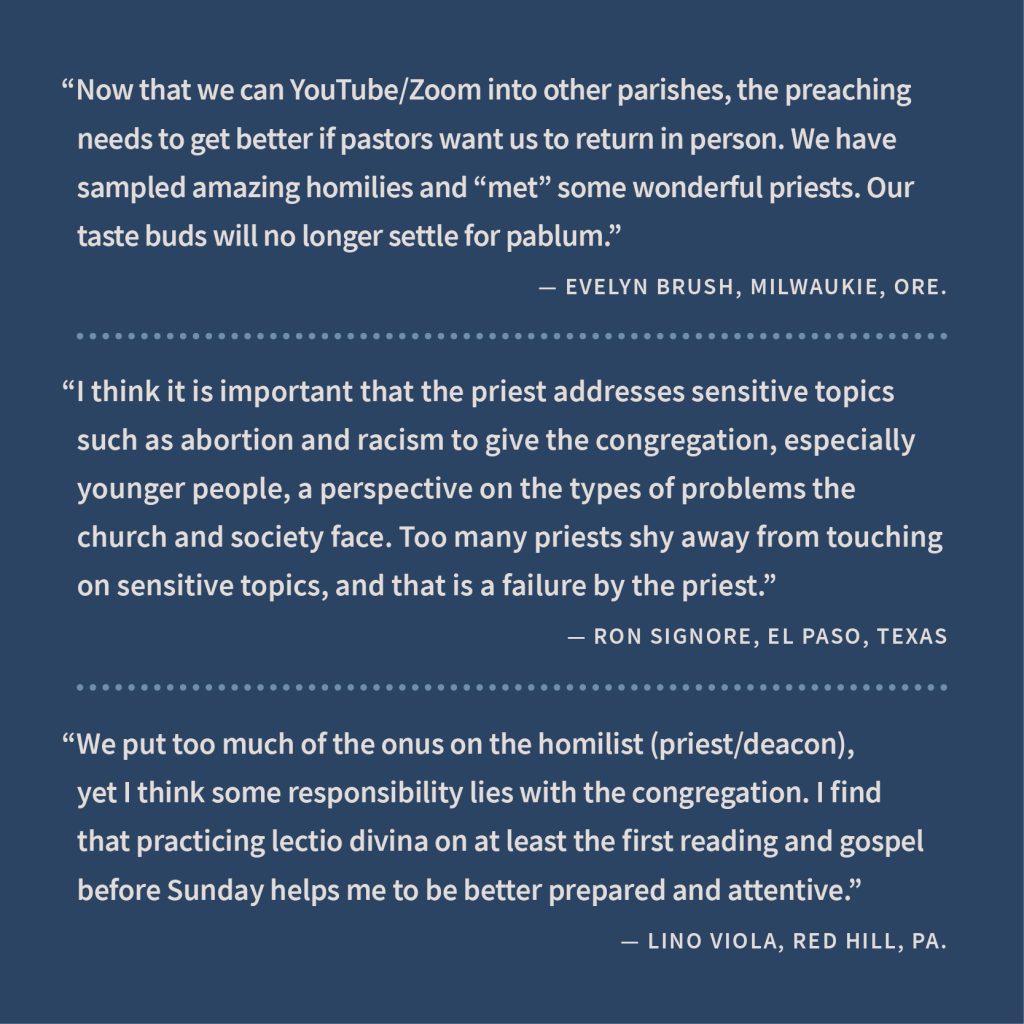

I wager most of us agree on several homily “don’ts.” Don’t make the homily a partisan diatribe. Don’t use it as a time to do parish business. Don’t ramble. Don’t paraphrase the scripture readings that the congregation just heard proclaimed. Beyond these, preaching put together with a lack of thought and consideration for those listening can bore, alienate, or, worse yet, wound deeply.

For the gospel to take root and grow, attention must be paid to the selection and crafting of the seed as well as its delivery. Like the seeds in the parable of the sower, preaching that finds fertile soil in the community leaves people moved, convicted, encouraged, and inspired.

Speak to a specific congregation and context

A preacher must look at their congregation with the interest, patience, curiosity, and rigor of an anthropologist. While there is value in “homily helps” as points of departure, a “canned” homily won’t make as powerful of an impact as one that is uniquely geared to a particular community in a particular moment. What assumptions does the preacher make about the congregation, the questions they are asking, the challenges they are facing, the hopes and fears within them?

The 1982 U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops’ document on preaching, “Fulfilled in Your Hearing,” is divided into four sections: assembly, preacher, homily, and homiletic method. Notably, the assembly comes first. Knowing the assembly—the languages they speak, the allusions and examples that will resonate with them, the experiences they’ve lived—is the first step in crafting preaching that will land. The sower must know their landscape well before setting out.

A preacher must also reflect on their own identity, know their blind spots, and be aware of the human tendency to universalize one’s own experience. This is especially important when there are different identity markers between the preacher and the congregation; for example, a white deacon serving a congregation that is primarily people of color or a young priest preaching to a congregation of retirees. I remember a well-intentioned but cringeworthy homily about the call to offer charity to those in need. The preacher assumed that the listeners were like him—middle class and relatively privileged—when in fact the majority were economically disadvantaged. References in the homily to retirement savings and expensive vacations didn’t resonate with those listeners, to put it mildly.

Pray and remain faithful to the text

“Breathe in a prayer, breathe out a preaching.” Dominican Sister Ann Willits often repeats this line. A preacher is believable and authoritative when listeners sense that they are trying to live faithfully. Like Jacob, who wrestles with God and emerges transformed, preachers engage in authentic preaching by wrestling with God in word, community, and relationship. Although this might sound elementary, carving out time for personal prayer and ongoing spiritual and human formation is imperative for those in full-time ministry.

For preaching to land, a preacher needs not only a genuine life of prayer but also a commitment to scripture. It’s easy to cut corners on study, but a preacher’s job is to understand the many contexts of scripture: Jewish cultural norms in first-century Palestine, Mosaic law, and the early communities St. Paul wrote to, for example. In the lectionary, we might get a short snippet from the Hebrew scriptures and most Sunday Mass-goers won’t have a clue about the political, social, and historical context of that reading. The preacher helps build a bridge between the world of the text and the world of the listeners. More importantly, when we proclaim readings in church that can and have been used to justify slavery, the subjugation of women, anti-Semitism, and a variety of other evils, a responsible preacher will unpack and contextualize these readings in the homily. One of my most humbling moments in ministry was when a rabbi kindly and pastorally pointed out that a reflection I’d given at an interfaith gathering, based on a gospel passage where Jesus clashes with the Pharisees, was problematic. This conversation led me into deeper study of Jewish–Christian relations and has impacted my preaching ever since.

Deliver it well

It’s hard to pull good ideas out of a rambling homily. Preaching that lands has a structure that helps the listener metabolize the message. This can look like asking a question and then answering it, presenting a thesis and then developing it, opening with a personal anecdote and then connecting it to one of the readings, or choosing a key word or image around which to shape the homily. Structure helps listeners know what the takeaway is.

Similarly, delivery matters. The most eloquent message won’t land if the preacher doesn’t enunciate, has distracting hand gestures, talks too fast, or trails off at the end of sentences. The preacher who never looks up from their manuscript won’t connect with their listeners either.

Ask questions

It can be tempting for the preacher to become the “sage on the stage,” seeking to offer a carefully prepared presentation as a theological and spiritual expert. However, the homilies that often have the greatest impact are the ones that are centered not on catechism-style answers but rather thoughtful, well-crafted, intentional questions.

A former pastor of mine once asked at least two or three “what if?” questions in almost every homily, and then he would pause to let them linger in the air. An honest, piercing question can stir the soul far more than expert answers.

It’s especially important to assume this posture of humility, curiosity, and cowondering on occasions when difficult pastoral questions are alive in those listening, whether because of the content of the scripture readings or the context of the Mass. The homily at the funeral of someone lost to suicide or drug overdose is a moment to offer accompaniment, presence, and empathy more than answers or platitudes. The Sunday gospel reading of Jesus’ teaching on divorce is an opportunity to respond to the hurt, disappointment, and shame that is likely present in many Mass-goers.

This posture of humility, curiosity, and cowondering is also necessary when touching on themes that may be controversial or stir strong emotions. It’s tough for a preacher to engage a hot topic such as war and peace, human sexuality, or racial justice. But the answer isn’t simply for preachers to play it safe and avoid these subjects.

“Preachers who avoid every thorny matter so as not to be harassed . . . do not light up the world,” writes St. Óscar Romero, the martyred Salvadoran archbishop, in his book The Violence of Love.

Even though our context and technology are wildly different from the time of the Hebrew prophets and the first followers of Jesus, the fundamental hungers of the human heart are unchanged. Human beings, individually and collectively, still ask big questions about who we are, what we’re doing here, and what it means to live with meaning. We still experience love and loss, failure and forgiveness, hope and heartbreak. And God still desires to meet us where we are and as we are in word, sacrament, and community. The gospel—deftly wielded, crafted, and sown—can still yield hundredfold, time and again.

This article also appears in the May 2022 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 87, No. 5, pages 16-20). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Unsplash/Gabriella Clare Marino

Add comment