On June 25, 1975, Michael “Casimir” Cypher was arrested and executed by soldiers in Honduras, thereby becoming the first of several U.S. missionaries to be murdered in Latin America over the past half-century. Surprisingly, his story remains largely unknown, even in his native country. An unassuming Conventual Franciscan assigned to the remote Honduran department of Olancho, Father Casimir had launched his ministry at a time when the global Catholic Church and Latin America itself were both on the cusp of momentous social change and upheaval.

After 1492, Christian missionaries were tainted with complicity in the creation and perpetuation of Western imperialism and its negative effects on indigenous peoples. This historical indictment is largely true if restricted to the pre-Vatican II era, but the Council (1962-1965) took great strides in rectifying the Catholic Church’s past missionary failures. In Ad Gentes (Decree on the Church’s Missionary Activity), it called on missionaries to immerse themselves in the cultures of those they serve, and in Gaudium et Spes (Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World), it noted that to merely dispense the sacraments and teach Catholic doctrine was insufficient. Although these were important, missionaries should also accompany the marginalized in their struggle for justice.

In 1968, inspired by the Council, Latin American bishops met in Medellín, Colombia, to apply its principles to the Latin American situation. In the conference’s final document, the bishops declared that Latin America was marred by socioeconomic inequalities stemming from colonialism. In a startling admission, they added that the Latin American church was itself sinful, because it had been complicit in this unfair system. Change was needed and the church must reverse its course: It must now side with the marginalized masses as they struggle for justice.

The Second Vatican Council and the Medellín Bishops Conference had a deep effect on Catholic missionaries in Latin America, so much so that by the 1970s a significant number of them were living among and supporting the poor. But by doing so, they incurred the wrath of those who had long benefited from the unjust system. They, along with those native priests and lay church workers who sympathized with the poor, were now seen as “communist” agitators and instigators of social unrest. They had become in the eyes of the rich a cancer to be eliminated. By the last quarter of the 20th century, missionaries began to receive death threats, and some were kidnapped, tortured, and even murdered. This was especially so in the countries of Central America, where Father Casimir would become one of the earliest victims.

Humble beginnings

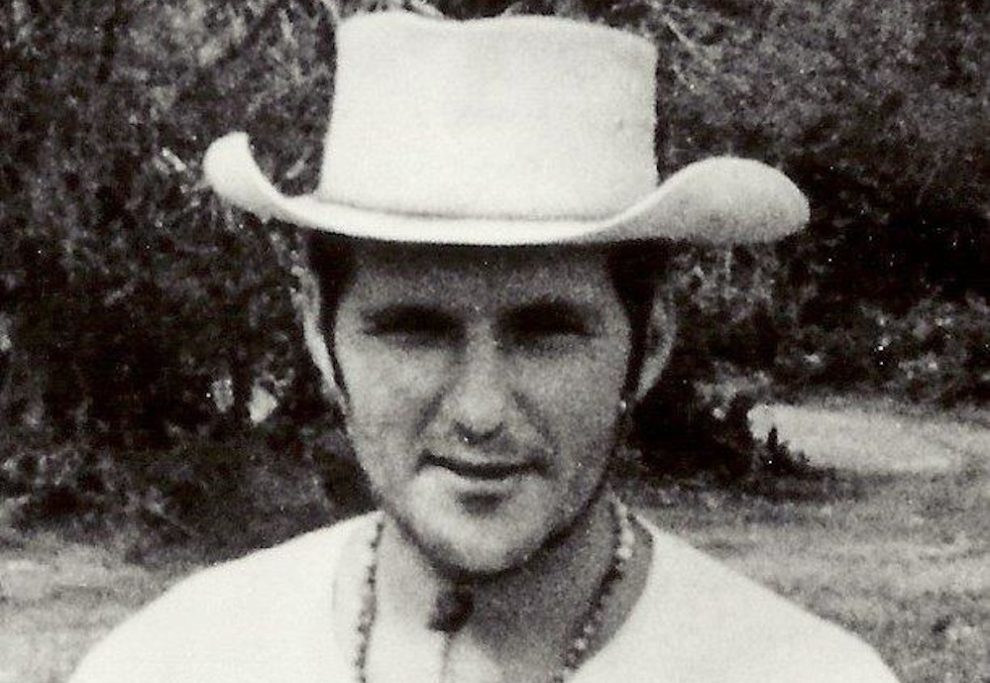

Michael Cypher, born on January 12, 1941, was raised with his eleven siblings on a small cattle farm near Medford, Wisconsin. Life was hard and the family lived simply, with few if any luxuries. Michael entered the seminary at age thirteen and was ordained a priest in 1968, taking the religious name Casimir. He is remembered by classmates and teachers as a mediocre student, but one who loved physical labor and excelled at anything that involved working with his hands. He took no interest in his appearance, habitually looking disheveled. He continuously misplaced things, such as car or house keys, and often exasperated others with his absent-mindedness, a trait that followed him all his life. As Father Philip Wozniak, a fellow Conventual Franciscan, recalls: “He made too many appointments for the same hour and the same day, and he frequently would not be at home when all these people arrived.”

Following his ordination, he was assigned to a parish in Illinois, but was not wholly content there. He wanted to minister to poor, struggling people, like the farmers he had known in rural Wisconsin and, consequently, felt called to the missions in Latin America. He knew no Spanish, however, so his superiors transferred him to a Spanish-speaking parish in Hermosa Beach, California to gain familiarity with the language. He was not there long when his eccentricities earned him the moniker “Father Colombo,” in reference to the unkempt detective in a popular television series.

His purpose, he apparently decided, was not to be comfortable but to help the poor.Leonard Wibberley

Leonard Wibberley, a parishioner and well-known novelist, in an op-ed written after Cypher’s death, noted that his initial impression of the young priest was that he was “dull” and “stupid,” and thus he had treated him in a disparaging manner. But when by chance the novelist encountered Cypher alone in the parish schoolyard and awkwardly offered him his hand, he realized that he had misjudged the priest: “[H]e was charitable enough to take it,” writes Wibberley, “though I deserved to have him ignore me, for I had been a pompous ass in the way I had treated him.”

Thereafter, Wibberley came to see and admire the spirituality and compassion that lay beneath the surface of Casimir:

I suppose, [he] could have stayed in Hermosa Beach or some equally comfortable parish… But he got it into his head that that wasn’t what he had become a priest for; his purpose, he apparently decided, was not to be comfortable but to help the poor… and somehow… he got himself transferred from comfortable Hermosa Beach to not-so-comfortable Honduras.

Far-flung places

In October 1973, Mike Gable, a lay missionary, met Casimir as the latter disembarked from a plane in a cow-pasture that served as a landing strip on the outskirts of Gualaco. Like other small towns in the isolated department of Olancho, Gualaco was rural, underdeveloped, and dominated by a few rich cattlemen. The vast majority of its residents were campesinos, who worked long and hard to barely survive. Inspired by Vatican II, Olancho Bishop Nicholas D’Antonio had launched an impressive reform program, but more priests were needed for its success. Cypher was recruited to assist Father Emil Cook, the pastor in Gualaco, and Gable awaited him with great expectations.

But like so many others before him, Gable was not terribly impressed with Casimir, especially because the priest’s Spanish was woefully lacking. Cook had hoped that the new missionary could assist him in teaching local boys at the minor seminary, but since Casimir’s language limitations made this impossible, the pastor assigned him the physically grueling task of visiting the many remote hamlets of the parish. Accompanied by local lay catechists, Cypher would spend weeks at a time trekking over rugged mountain trails, bringing the sacraments to the most deprived parishioners. Yet Casimir thrived in this new ministry: These were his people, humble and hard-working, just like those from his rural Wisconsin roots. With them, he felt comfortable.

Perhaps unwittingly, Casimir fit the profile of the Vatican II missionary, eager to immerse himself in the lives of the people he served. Roger García, who had been a student at the minor seminary in Gualaco in the mid-1970s and came from a poor peasant family, sums up the simple Franciscan perfectly in an e-mail he recently sent to the authors:

Father Casimir lived like the poor people he evangelized. He walked like the people to move from one community to another or he did it on the back of a mule. He [ate] the same foods, lived with them when he visited them in their humble homes… He shared their culture.

Although Cypher never mastered Spanish well, he found ways to converse with the campesinos in their simple homes made from mud and sticks. He learned from them about the overwhelming poverty that beat them down and each year took as many as half their young children’s lives. He loved visiting these remote hamlets and eventually spent about eighty percent of his time doing so. When he was back in Gualaco, he shared a small room with Gable. It had no indoor plumbing or electricity, and they used a nearby stream to bathe. Mike looked forward to Casimir’s return from the hamlets. The priest would chew on a cigar, while regaling Mike with his latest adventures on the rugged trails. He shared his poems and art work with Gable and the two often stayed up late at night discussing spiritual—and sometimes not so spiritual—matters.

They frequently talked about poverty in Honduras and Bishop D’Antonio’s programs for the marginalized. Cypher knew that campesinos had formed peasant unions and that tensions were building between them and the cattlemen. He realized that the rich held the church responsible for peasant unrest and that priests, especially foreign ones, were in constant danger. Following the advice of Bishop D’Antonio, he avoided any direct involvement in politics.

Gable viewed Cypher as his best friend, and when the lay missionary returned to the United States following the completion of his mission commitment, he asked his friend to preside at his wedding. Casimir, in the United States at the time for medical treatment, gladly accepted. It would be the last time Mike saw him alive.

The end of the journey

Upon Cypher’s return to Olancho, he was appointed pastor for San Esteban, a town not unlike Gualaco. While driving a sick parishioner to a doctor in late June 1975, he damaged his borrowed pickup truck. The following day he drove it to Juticalpa, the capital of Olancho, for repairs. Since he had to stay there overnight, he slept at the bishop’s residence. Coming from remote San Esteban where there was little communication with the outside world, he was unaware that the local affiliate of the National Peasants Union was planning to take part the next morning in a march to Tegucigalpa to demand that the government implement a long-ignored land reform act. Someone must have filled him in, however, because he celebrated Mass for the union members just before the march commenced.

Following Mass, the military attacked the union’s headquarters, killing several campesinos. Cypher was arrested and charged with “instigating a rebellion.” He was stripped of his clothes and taken in his underwear, along with six union leaders, to the local jail. At 1:30 a.m. the seven prisoners were handcuffed and taken by soldiers to the ranch of a rich cattleman, where they were executed with three others who had been arrested separately.

We may not be missionaries, but we can walk with the marginalized of our own day.

Advertisement

Father Casimir was 34 when he died and had been a missionary for only two years. Yet in this short time he had immersed himself into the lives of the poorest of the poor and accompanied them in their struggles. He paid for his commitment with his life. He exemplifies what Vatican II had asked Catholic missionaries to be and as such is a model for missionaries today.

He also serves as an example for the rest of us. We may not be missionaries, but we can walk with the marginalized of our own day—with poor refugees at our borders, with Black people who are struggling to convince us that their lives matter, and with all who thirst for justice. We can educate ourselves on their plight; we can take the time and make the effort to listen; and then we can accompany them in their struggles for dignity.

All images: Courtesy of Donna and Edward Brett

Add comment