How would you feel about someone skateboarding in a church? I imagine many of us instantly recoil at the thought. But what if it was a church that was no longer in use?

It’s not just a theoretical question. Santa Barbra in Llanera, Spain, a lovely little Romanesque church, is now a skate park emblazoned with rainbow-colored murals and a halfpipe. But you don’t have to go to Europe to skate or BMX freestyle in a church. You can go to “Sk8 Liborius,” formerly Saint Liborius, a cavernous Gothic church turned skate park in St. Louis. Such reuse of sacred spaces raises a number of questions: What should we do with old churches? And, what makes a place sacred in the first place?

The famous French artist Marcel Duchamp confounded the art world of his day by arguing that something could be a work of art simply because the artist says it’s a work of art. Is this the case with sacred spaces or holy buildings? Are they holy simply because we say they are holy, or is there something more to it? For Catholics with a sacramental worldview, there certainly is.

Some places are deemed sacred because some holy event or miraculous occurrence is believed to have transpired there. Other places are considered sacred because holy objects, such as relics, are housed there. Still other places are considered sacred because some tragedy has occurred in that exact location.

Often in this line of thinking distinctions are made between what is and what is not holy. However, even for those who see everything as a gift from God, and as such bearing some level of holiness, distinctions can be made about the level of holiness an object or place possesses.

The pressing question then is: with the proliferation of churches that have fewer and fewer people attending, the expenses of maintaining large and aging church buildings, burgeoning homeless populations, the reality of migration, housing limitations, and concern for working towards a sustainable future, what should be done with old churches that dioceses can no longer afford to keep?

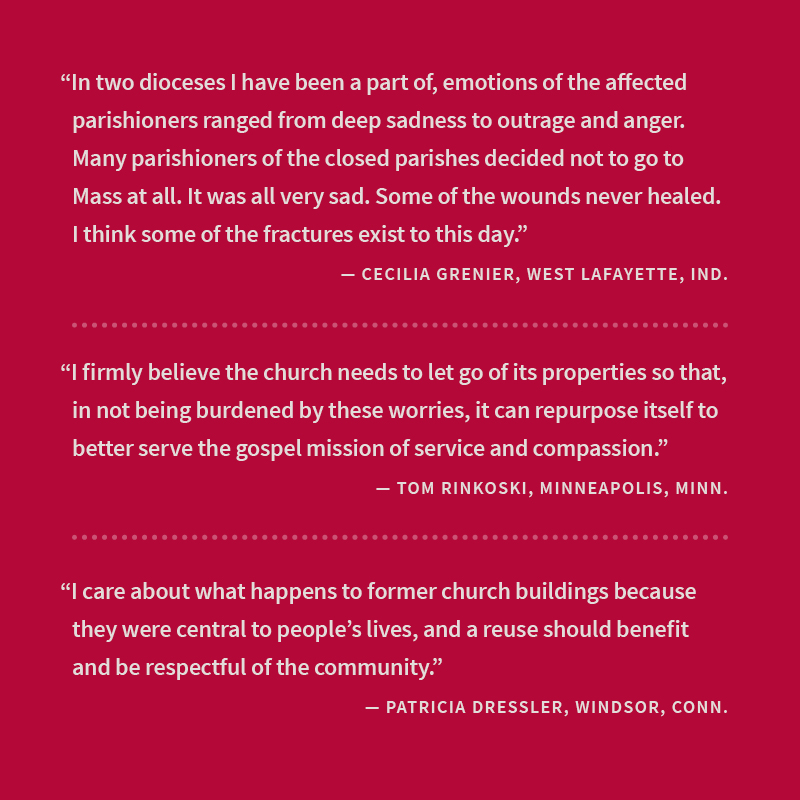

Clearly this is a multifaceted question touching upon numerous aspects of our faith, from theological concerns to the demands of justice. What should also be acknowledged is the strong emotional attachment we have to our places of worship. After all, these are the spaces we use to ritualize the most significant moments in our lives. Our churches are where families and friends celebrate new life in baptism, the joy of love in marriage, and the sorrow of death at a funeral. We gather in our churches to encounter God. Whether we are asking for help amidst life’s challenges, offering praise and thanksgiving, or receiving the Eucharist, we utilize these spaces to nurture and sustain our relationship with God. In fact, relationship is the key to answering the question of what to do with our underused or deteriorating churches.

In their article on Trinitarian spirituality in The New Dictionary of Catholic Spirituality (Michael Glazier), Catherine LaCugna and Michael Downey define holiness as “good relationship.” After all, if God is loving relationship, then building and sustaining good and loving relationship is our model of holiness.

If we then use “good relationship” to define holiness, what would make a church building holy beyond its originally intended use? In essence, how do we continue to imbue these spaces with our relational values after they cease to fulfill their original purpose?

Not unsurprisingly, the example of so many women’s religious orders in this country is instructive. Religious sisters in the United States have possessed the ability to see the mission of the church as it addresses the needs of society in broad and creative ways.

So many of the schools and hospitals in this country were begun by vowed religious women. They not only administered and staffed hospitals but created networks to sustain them. With great foresight, as their numbers dwindled they sought to imbue these institutions with their deep Christian values. They may no longer staff these hospitals, but their charism lives on in their walls.

Our churches, and the land they sit upon, are resources given to us by previous generations to do God’s work. What are some creative ways they can do that even after they no longer serve as places of worship?

We could think a bit more about our fellow Christians. Often when a diocese is considering the future of a struggling parish they may “merge” it with another parish. Yet, if a community eventually has to leave a church building, why not consider offering the building to another local Christian community? In many big cities the streets are lined with storefront churches. Likewise, some congregations may have growing communities, but their buildings are in far worse condition. Why not work ecumenically to allow some of these historic places of prayer and worship to continue their mission? Far too much effort has been put into naming what divides us as Christians rather than what unites us. If Christianity is going to be credible in the future Christians need to act more like “brothers and sisters in Christ.” Can we share our resources with our brothers and sisters?

Pope Francis famously said early in his pontificate that “The thing the church needs most today is the ability to heal wounds and to warm the hearts of the faithful; it needs nearness, proximity. I see the church as a field hospital.” Francis has a gift for creating evocative images to stir the imagination. But what if we utilized our underused or deteriorating churches to do just that?

The elderly population continues to increase in our country. As people live longer, we are more aware of the care an aging population requires. Often the focus is on their physical needs, but anyone who has a relative in an assisted living facility or regularly visits a nursing home knows the most acute needs are relational: emotional, social, and spiritual. While small staffs often try to attend to these needs, it is very difficult. Likewise, the aging population is frequently relocated to be in a nursing facility closer to a relative. They then miss their parish community and place of worship. Often their spiritual needs are difficult to attend to.

But what if their church was renovated to become their home as a nursing/assisted care facility? So many aging parishes are populated mostly by an elderly population. They have financed the parish in part because of their significant memories there. The elderly population could now live there together. They would feel closer to God and not have to leave their community. The sanctuary itself could be retained as a chapel, while the rest of the building could be renovated to serve the needs of the community.

Another way the church can be a field hospital is by renovating the spaces to address so many of the social sins of our day. At every Mass we are nourished by the Eucharist and then sent forth to proclaim the good news in word and in deed. In essence we are sent into the world to be Eucharist for others.

How do we do this? Obviously, the church’s social teachings are a rich treasure of possibilities, but the simple instructions we encounter in Jesus’ parable of the last judgment in Mathew’s gospel—feed the hungry, care for the sick, visit the imprisoned—are a good place to start. Now imagine those things taking place in the very place we once received the Eucharist. The very spot we deemed sacred because of our encounter with Christ is now made sacred by our encounter with strangers who come for food, shelter, or healing.

Recall how Pope Francis asked parishes through the world to take in a migrant family in this time of vast migration. These older church building can be “sanctuaries” for those fleeing violence, those seeking food and shelter, and those simply trying to rebuild their lives.

Another way to use our sacred spaces to be places of healing and “good relationship” is to use them to aid in the care for our common home. In her recent book, The Meal that Reconnects: Eucharistic Eating and the Global Food Crisis (Liturgical Press Academic), theologian and Society of the Sacred Heart Sister Mary McGann, after a thorough critique of the industrial food system and its impact upon the Earth, offers some very practical ways a parish can begin to address the environmental harm caused by the industrial food system. One suggestion she offers is for parishes to use part of their property to create community gardens. The food grown there could then be used to help those in the local community who are in need.

Our buildings and sacred spaces are meant to serve a mission. They are not mere objects for us to use for profit.

Sometimes our older churches are in such poor condition that not much can be done with them. In these instances, perhaps we should think of the land itself. In a very real sense this is still holy ground. It can bring forth new life and nourish the community. The building can be removed, and the land can be turned into a community garden named after the patron saint of the parish. This garden can be a mission of the former parish community. Here they will not only provide food for those in need but contribute to a healthier planet with trees and green space for all. A special place in this garden can be set aside for prayer. Even some of the significant statues can be utilized, reminding everyone of God’s continued presence.

Underlying all of these suggestions is the reality that the church is missionary by its very nature. Our buildings and sacred spaces are meant to serve that mission. They are not mere objects for us to use for profit. Nor are they ends in themselves, such that the community cares more about keeping a building rather than attending to the call of the gospel.

The church is missionary, and our church buildings can help us in that mission. We can continue to make them holy through the relationships we form in their walls and on their grounds. In fact, they can become a source of pride for the community. We can look upon them and say, “Look how we have honored these sacred spaces and found a creative way for them to continue to serve their missionary purpose.”

This article also appears in the November 2021 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 86, No. 11, pages 27-31). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Flickr/Frodo DKL

Add comment