My first encounter with Oscar Wilde was probably much the same as yours: I was assigned The Importance of Being Earnest in high school English class. I read about half of it, then filled in the gaps with the 2002 film adaptation. I found it amusing, but not much more than that, and our brief classroom discussion of Wilde’s famous quips and epigrams (e.g., “Life is far too important a thing to ever talk seriously about”) seemed to confirm my initial judgment that Wilde was a very funny, but ultimately somewhat vain and superficial writer. And that was about it.

Many years later, I ended up reading two of Wilde’s final works—De Profundis and The Ballad of Reading Gaol—and was shocked to discover that what I initially believed to be little more than a puddle went far deeper than I had imagined. In them, the man I knew best for a series of eyeroll-inducing puns meditated on life and death, sin and guilt, and the depths of human cruelty, and he seemed to do a better job of it than many philosophers and theologians.

Some historical context from Wilde’s own life is helpful in explaining what brought a man who avoided the serious like the plague to write so solemnly for the hundred or so pages of De Profundis. You might know this story, but even if you don’t, it will probably sound unfortunately familiar—the tragedy and persecution it contains still has its resonances today.

Wilde was gay, but in late 19th-century London that certainly wasn’t something to be open about. At the peak of his fame, it’s likely much of high-society London had their suspicions about the dandyish writer, but it wasn’t until 1895 that Wilde’s secret truly came to light. That year, Wilde had become embroiled in a legal battle with the Marquess of Queensberry. During the trial evidence was found that Wilde had been engaged in a secret affair with Lord Alfred Douglas, the marquess’s own son. Wilde abandoned his case, but it was too late: He was arrested, tried, convicted, and sentenced to two years of hard labor.

Whatever you picture “hard labor” to mean, Wilde probably had it worse. The Ballad of Reading Gaol (pronounced “jail”), a poem he published after his release, details just some of the cruelty he observed and experienced himself. The ballad centers around the public hanging of another prisoner, Charles Thomas Wooldridge, but also notes that the prisoners “broke the stones” and “tore the tarry rope to shreds, with blunt and bleeding nails.”

After his release in 1897, Wilde spent the remainder of his life in dire straits. His health rapidly deteriorated after the brutal treatment he endured, and he was forced to live in exile under a pseudonym. He died in 1900 at age 46.

The last three years of Wilde’s life were a marked departure from the decadent, glamorous lifestyle that he had lived prior to his imprisonment, not only materially but also spiritually. It was a time of spiritual renewal. He re-embraced his childhood Catholicism and even went so far as to ask the Society of Jesus to lead a six-month retreat for him, though his request was denied for undisclosed reasons. Much of the rest of his time was spent advocating for prison reform through a campaign of letters, essays, and poems, of which The Ballad of Reading Gaol was the most successful.

The moment of repentance is the moment of initiation.

Oscar WildeAdvertisement

Many of Wilde’s contemporaries questioned the authenticity of his conversion, and in the century since those questions haven’t much abated. Some point to his abuse of alcohol or even his briefly rekindled relationship with Douglas as evidence that his heart wasn’t really in it. The extremely cynical might go so far as to suggest that “devout, exiled prison reformer” was merely another costume which enabled a man who loved the limelight to continue strutting upon the stage. But, after having read De Profundis, it’s hard for me to take those accusations seriously.

De Profundis, which was not published until 1905, five years after Wilde’s death, is actually a letter Wilde had written to Douglas in prison but was forbidden from sending. The first half of the letter mostly examines Wilde’s relationship with Douglas. At times it is critical and loaded with grievance. At others it seems to speak from a place of genuine love. But, for those less interested in the internal drama of a torrid love affair, it’s the second half of De Profundis that gets interesting.

The second half of the letter explains Wilde’s motives for converting and outlines a new personal philosophy that stands in stark contrast to the freewheeling decadence of his youth. At the core of this philosophy lies what I can only call a mystical theology of suffering and reconciliation. There is a passage within the letter that I struggle with to this day, but it seems to speak to some truth that lies just beyond words:

The world had always loved the saint as being the nearest possible approach to the perfection of God. Christ, through some divine instinct in him, seems to have always loved the sinner as being the nearest possible approach to the perfection of man. His primary desire was not to reform people, any more than his primary desire was to relieve suffering. . . . Of course the sinner must repent. But why? Simply because otherwise he would be unable to realise what he had done. The moment of repentance is the moment of initiation.

Now, those more well-versed in theology than I could certainly pick apart this passage and find plenty of heterodoxy: Wilde himself admits that this “is a dangerous idea.” But, from where I’m standing, there are few better poetic images of the mystery of reconciliation.

Sin and suffering haunt this world, just as they haunted Wilde. Some of it is of our own making, to be sure, but much of it is also inflicted upon us by forces outside our control or comprehension. Christ died for us, yet the suffering continues. No matter how many times I step into the confessional and do my penance, the sin and injustice continue.

So why continue the process? Perhaps because, as Wilde suggests, we cannot begin to understand what we have done and what we are capable of—both good and evil—unless we do. Perhaps I can only understand the glory of the heights through being mired in the depths. Perhaps it was the very injustice that Wilde suffered that enabled him to campaign for justice for others.

Perhaps I can only understand the glory of the heights through being mired in the depths.

Advertisement

That is not to say that this somehow makes the injustices any of us suffer somehow good—they are injustices, after all—but that is the mystery of it. God can somehow pull good from evil. Even as I fail to do good, and even as others fail to do good to me, the opportunities to rectify injustice don’t diminish. They may even seem to grow.

I don’t know if this idea is comforting or unsettling. But, either way, I think the only thing to do is forge onward. For my part, I just hope I can recognize those opportunities to do good as I continue to stumble into them.

This article also appears in the November 2021 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 86, No. 11, page 45-46). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

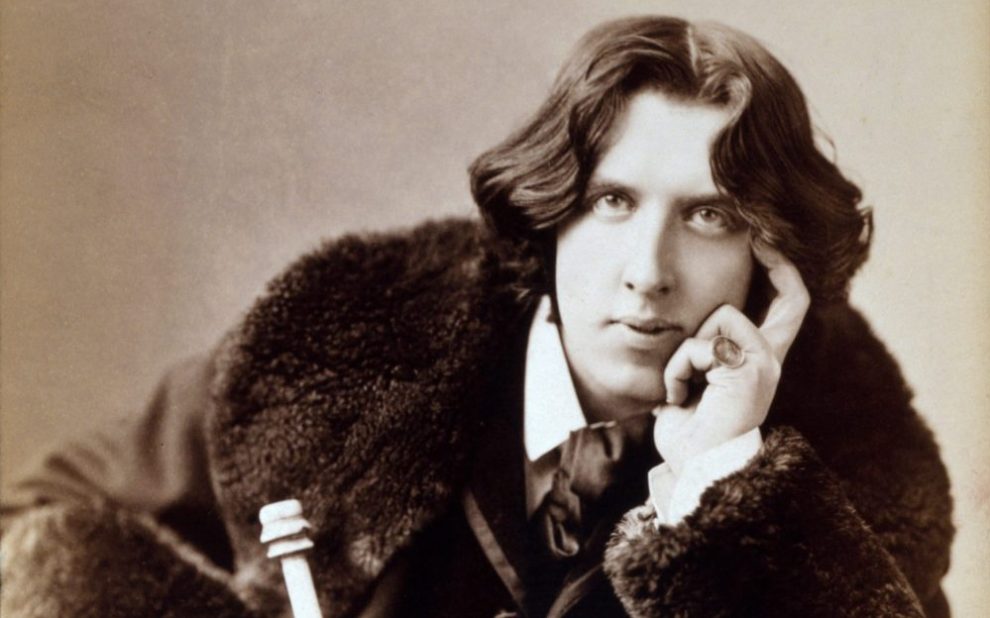

Image: Wikimedia Commons/Library of Congress

Add comment