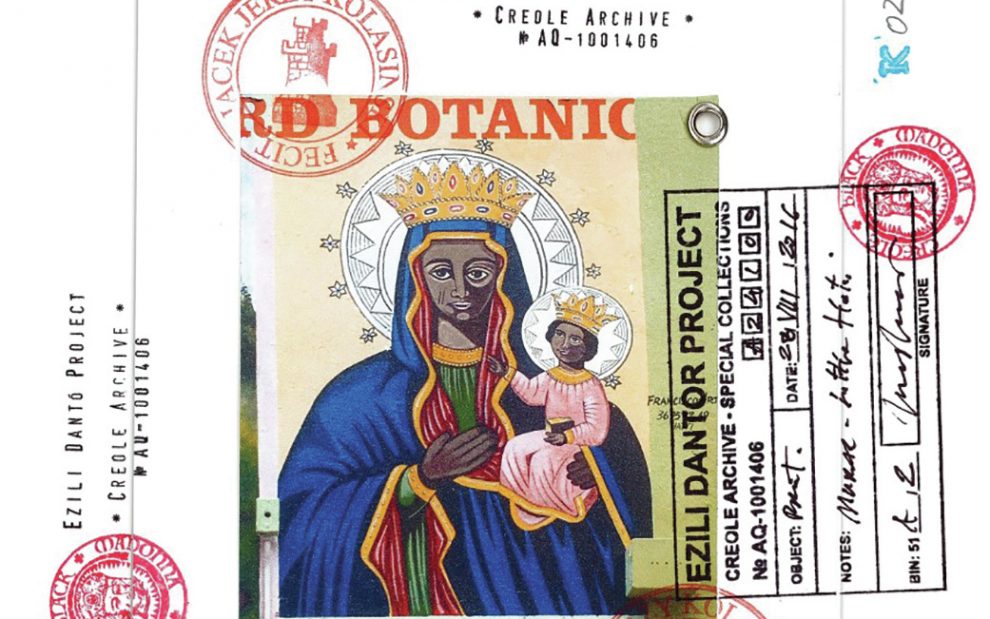

Our Lady of Częstochowa is striking in many ways, but the scars on her right cheek make her truly unique. They are battle scars that the Black Madonna suffered for the Polish and Haitian nations. And maybe for you.

Our Lady of Częstochowa’s Polish homeland, on the open plain of Eastern Europe, is a vulnerable place. The Poles have been buffeted by repeated Mongol invasions, partitioned by European powers, and occupied by the Nazi and Soviet regimes. Yet many Polish people believe that there is a spiritual force at work protecting them and holding their nation together.

This belief comes from a legend about how the spirits led the Poles to their homeland. It is a story of three brothers who embarked on a journey. Čech, the oldest, went west and became the Czech people. Rus went east and became the Russian people. Lech, the youngest, went north. While hunting, his arrow led him to a white eagle framed by the setting sun. Lech tried to take one of her three eaglets to raise as his own, but the eagle fought back until blood poured from wounds inflicted by Lech’s sword. Lech finally realized that there was a spiritual force at work and relented. He settled there, naming the place Gniezno, from gniazdo, Polish for “nest.”

The white eagle became a national symbol in Poland but was only a partial image of the Poles’ spiritual mother, who fully revealed herself in 1382. Legend has it that Our Lady of Częstochowa dates back to Prince Ladislaus, who carried a mysterious image of Our Lady painted in the Byzantine style, dark-skinned with a scar on her throat from a Tatar-Mongol arrow. She was ancient; some say that St. Luke painted her on a plank from a table made by St. Joseph. When Ladislaus got to the Church of the Assumption at Jasna Góra, meaning “bright or clearly seen mountain,” his horses refused to travel any further. The church became Our Lady’s new home, and she took the name Częstochowa from the surrounding town.

Our Lady of Częstochowa quickly became a pilgrimage site and, like the Poles, a victim of invasion. On Easter Sunday in 1430, Hussites sacked the monastery and hacked Our Lady of Częstochowa to pieces. In the aftermath, she was put on display in Krakow in mutilated form.

But the Black Queen would not die. She was anonymously restored by someone totally unfamiliar with Eastern Orthodox iconography, creating a unique hybrid of Eastern and Western styles. The original image remains below the restoration, forever hidden. Yet her scars remain. Legend has it that every time someone tries to repair the scars they miraculously reappear.

Hundreds of years later, Our Lady of Częstochowa returned to Bright Mountain. In 1655 Jasna Góra survived a monthlong siege by Swedish and German forces. The next year, on April 1, King John II Casimir Vasa declared Our Lady Queen of Poland. She played a protective role in battle and was displayed on flags and chest plates. Numerous peasant revolts flew her banner and invoked her protection.

Legend has it that every time someone tries to repair the scars they miraculously reappear.

Advertisement

Horses were replaced by tanks, but Our Lady of Częstochowa fought on. In 1920, as Russian forces massed along the Vistula River, Our Lady of Częstochowa appeared in the clouds and turned them back. Even World War II, during which 6 million Poles died—about 17 percent of the population—did not destroy Our Lady of Częstochowa or the Polish nation. She became a symbol and guiding force of the Solidarity movement, which, with the help of St. Pope John Paul II, threw off the communist regime.

Although forever Polish, Our Lady of Częstochowa also chose another mountain nest: Haiti, meaning “flower of high land.”

On the night of Sunday, August 21, 1791, during the week of her feast day, rebel leaders gathered in Bwa Kayiman, or “Alligator Woods,” to formalize their uprising against the most extreme slave society in the world. Slaves made up about 80 percent of the colony’s population. Sixty percent had been born in Africa and represented dozens of different nations. Those were the survivors; within five years of landfall, 50 percent of new slaves died.

At the August gathering, the rebel leaders called on the ancestral spirits. Cécile Fatiman, the famous green-eyed spiritual leader, felt the presence of a fierce spiritual mother. Those present took an oath to act in unison before God with this prayer:

The Good God who created the sun which lights us from above,

which stirs the sea, and makes the thunder roar . . .

throw away the image of the god of the whites,

who thirsts for our tears,

listen to the voice of liberty that speaks in all of our hearts.

Over the next week, 15,000 slaves rose up and destroyed almost 200 sugar plantations. It was the first act in the Haitian Revolution.

War ground on for years. European powers couldn’t accept a free Black republic or give up their lust to possess what was the richest colony in the world. In 1802 Napoleon Bonaparte, the emperor of France, sent more than 30,000 troops to reconquer the newly independent nation. Among them were 5,000 Polish legionnaires and devotion to Our Lady of Częstochowa.

The Polish forces suffered devastating losses. Hundreds succumbed to disease. Some went back to France. But a number defected to the Haitian cause, intermarried with the local population, and spread their devotion to Our Lady of Częstochowa to the Haitian people.

Numerous peasant revolts flew her banner and invoked her protection.

The number of Polish defectors wasn’t huge, but the symbolism was immensely important for the Haitian national consciousness. In the middle of brutal racist violence, a group of white Europeans fighting under a Sacred Black Queen with facial scarification similar to that practiced in many nations of West Africa switched to the side of the oppressed.

The people’s stories of Our Lady of Częstochowa especially resonated with Kongolese Catholics in Haiti, who have an intense Marian devotion and at the time made up about 40 percent of the Black population there. Our Lady of Częstochowa is the same spiritual mother and protector who visited Cécile Fatiman; she had been fighting with them all along.

Our Lady of Częstochowa, commonly known as Twa Mak (Three Scars) by the people in Haiti, became a vibrant part of Haitian spirituality. No doubt her dark color—which seems to come from the resin used to preserve her—appealed to the people. Yet it was the scars that showed her love: proof that she fought in the revolution, was wounded, and continues to fight in a land where each day is often a battle for survival.

In March 1983, St. Pope John Paul II visited Port-au-Prince at the end of his tour of Central America. He was famous for his skepticism of liberation theology and had just admonished liberation theologian Ernesto Cardenal in Honduras. Yet in Haiti, the land of Our Lady of Częstochowa’s second scar, he unleashed revolutionary energy with a call to action. At his last public appearance before his trip, he prayed before the image of Twa Mak to guide his journey. Then, before the Haitian people, she seemed to speak through him: “Something has to change here,” he said on his trip.

Something did. The people soon rose up and overthrew the Duvalier dictatorship.

One scar for Poland. One scar for Haiti. What of Twa Mak’s third scar?

From the beginning, Our Lady of Czestochowa has been a pilgrimage destination and a source of healing.

Maybe it’s for you. From the beginning, Our Lady of Częstochowa has been a pilgrimage destination and a source of healing. Grateful pilgrims leave ex-votos, or valuable offerings for favors granted. Offerings of gold were once melted down and encrusted with precious stones as a covering for the image. Today, hundreds of thousands of ex-votos wallpaper the shrine in Poland, including St. Pope John Paul II’s bullet-holed cassock and pieces of barbed wire from a concentration camp. She may protect nations, but individuals are also under her care.

Polish and Haitian devotion to Our Lady of Częstochowa lives on in the United States and is centered at her shrine in Doylestown, Pennsylvania. At 53 acres, it is among the largest religious sites in the country. Throughout the year, but especially on her feast day of August 26, busloads of Polish and Haitian pilgrims make the journey to implore her aid, give thanks for favors, and venerate the statue of St. Pope John Paul II for his role in fostering authentic freedom in their lands.

So the next time you are in the Philly area, stop by and ask for Our Lady of Częstochowa’s help. Twa Mak won’t give up on you. She’s got the scars to prove it.

Many thanks to Dr. Terry Rey and Dr. Jacek J. Kolasiński for their scholarship and conversation along with the work of Dr. Robbie Shilliam and Marek Czarnecki.

This article also appears in the August 2021 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 86, No. 7, pages 20-22). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Creole Archive Project – Little Haiti Mural (K022), Mixed media, 2018

Add comment