When I think of the Lakota way, many sacred items come to mind. The Sun Dance tree. The čhaŋnúŋpa, or sacred pipe. The drum. The prayer flags.

And the rosary.

Many may be surprised to learn that the rosary is an authentically Lakota prayer. But if you hear the story of the rosary’s origin with Lakota ears, you won’t be surprised at all. The story begins with St. Dominic (1170–1221), the founder of the Order of Preachers. Convinced that God called him to bring the Albigensians back to orthodoxy, he went to France and began preaching. Despite his oratorial skill and years of effort, he had no effect. Defeated, St. Dominic retreated into the wilderness where he fasted and prayed for three days.

A traditional Lakota wouldn’t miss the parallel with the haŋbléčheya, the vision quest. In this Lakota ceremony, a supplicant goes to a secluded place to fast and pray for a number of days, crying to the Spirits for a vision. The Spirits often answer with gifts of power, some of which end up becoming new ceremonies.

That’s how the rosary was born. Mary took pity on St. Dominic and gave him a new prayer ceremony. She told him that God initiated one of the greatest events in human history, the incarnation, “by sending down on it the fertilizing rain of the Angelic Salutation.” So must your work begin with “Hail Mary”—50 times counted out on beads while you meditate on the mysteries of salvation history, each prayer a single rose that together form a crown for our Blessed Mother.

Catholic theologian Karl Rahner made popular the practice of calling well-intentioned people of other faiths “anonymous Christians.” A traditional Lakota elder may chuckle and call St. Dominic an “anonymous Lakota.”

A traditional Lakota elder may chuckle and call St. Dominic an “anonymous Lakota.”

The rosary, like many aspects of Catholic spirituality, often intrigued Native peoples because of its embodied, tactile nature. Beads were highly valued in Native societies and became an important trade commodity. The earliest missionaries, such as the Jesuit Pierre-Jean de Smet, who crossed the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains numerous times, handed out rosaries to the nations with which they counseled.

One such encounter was with the great Lakota chief Sitting Bull in 1868. During the Great Sioux War, de Smet tried to bridge the warring parties. He and his Native guides sought out Sitting Bull’s band without the protection of the U.S. Army. De Smet made an offering of tobacco and was brought into the camp. After smoking the sacred pipe and counseling about peace terms, de Smet gave Sitting Bull his rosary. Sitting Bull kept it for the rest of his life.

The Black Robes (as the Lakota called the Jesuits) and the Lakota wore their rosaries like pieces of regalia. Regalia aren’t just pretty objects. They also have deep, symbolic meaning. In an oral culture, regalia often serve as memory aids. The rosary fit right in, with prayers linked to each bead and interior meditations that cycle through the entire life of Christ, a particularly useful learning tool for those new to the faith.

Many people associate the rosary with private devotion, but in the Lakota way it is a communal prayer. Families such as Servant of God Nicholas Black Elk’s pray it together daily and with the community in church. A beautiful snapshot is from Decoration Day, when people visit the dead by adorning their graves and leaving offerings of food. On the way to the cemetery, they pray the rosary. This is a fitting example, walking as a community to honor the ancestors as you walk through the life of Christ with the eyes of Mary.

The rosary also had an important healing role. Black Elk was one of many who shifted from traditional healer to catechist. Instead of visiting the sick to sing healing songs, he prayed the rosary with the family.

The power of the rosary bled into mainstream Lakota society. Traditional healer Pete Catches revitalized many Lakota ceremonies starting in the 1960s. A longtime Jesuit remembers Catches attending a wake at a small Episcopalian chapel. The church was full when Catches walked in. “Is there going to be a rosary?” he asked. Happy to hear that the prayer would be said for the journey of the deceased and for those who mourned, Catches sat down and joined in.

Many people associate the rosary with private devotion, but in the Lakota way it is a communal prayer.

Today, the rosary is less visible in Lakota Country than in the past. The Lakota, like all Americans, are wrestling with secularity, modern society, and the meaning of their Catholic inheritance, but with a massive complication: the legacy of cultural genocide. Yet the rosary is still there, still part of the vibrant Lakota spiritual way of life.

Like with so many spiritual teachings, Black Elk weaved these strands of his Lakota inheritance and the gospel message into a seamless tapestry. As an elder, he is remembered saying the rosary with a friend as he walked to church. At the same time, he prayed with his feet. The Earth is our Mother and sacred, he taught in The Sacred Pipe (University of Oklahoma Press). Therefore, “every step that is taken upon Her should be as a prayer.”

This is already beautiful, praying with your feet as you pray with beads, but a final detail brings this practice full circle: Black Elk measured his steps not in miles or time, but by the number of rosaries you could say on the way.

May we too learn to walk in such a sacred manner.

This article also appears in the May 2021 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 86, No. 5, pages 21-22). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

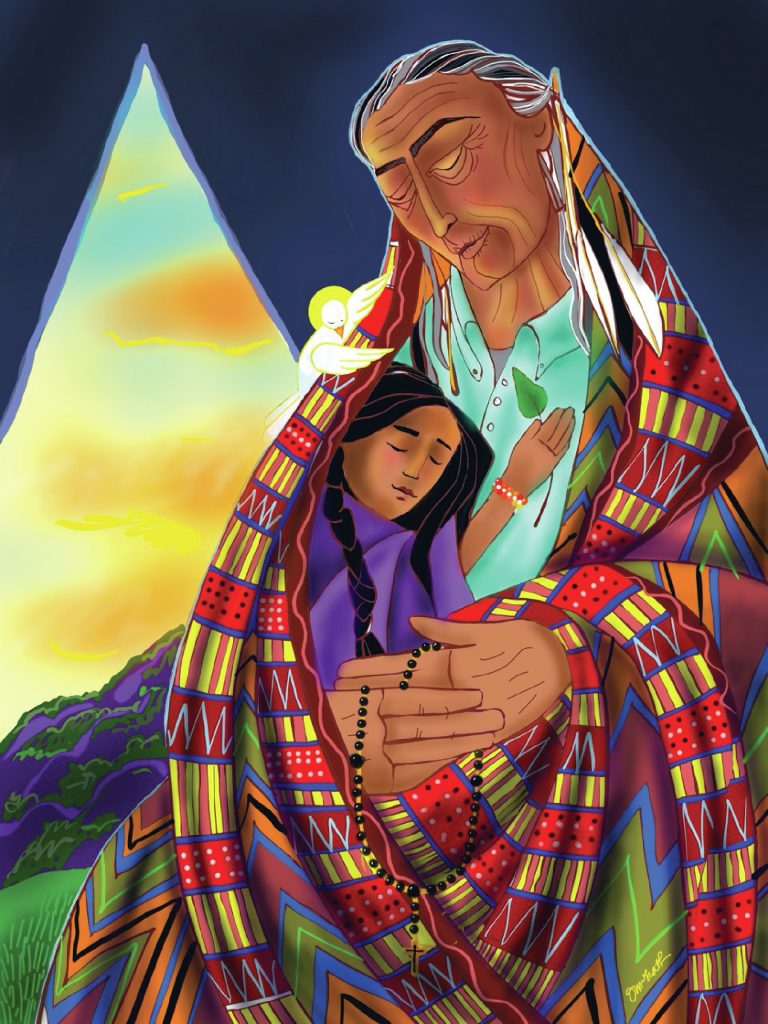

Image: Mickey McGrath

Add comment