Although many Catholics might find them unassuming, devotions and the popular piety that surrounds them are often met with scorn. They can be one of the largest wedges driven between Catholics and their Protestant friends and family. I cannot begin to count the number of people I’ve met who mistakenly believe that Catholics worship Mary and the other saints, or that Catholic statues and iconography are a form of idolatry.

In a similar vein, I’m reminded of a post that made its way around Twitter not long ago, with side-by-side images of a person praying with a rosary and another praying with a misbaha, the implication being that Catholics can’t be Christians because the way they pray looks an awful lot like the way Muslims do.

It is often other Catholics who can be the most suspicious of popular devotions, though usually not in the same sweeping fashion—when Catholics do it, it tends to be targeted at one or two devotions in particular, not the practice as a whole. Whether it is devotion to the Divine Mercy (we mustn’t forget that God is also full of wrath!), to Our Lady of Guadalupe (didn’t you hear that most scholars believe her apparition to St. Juan Diego wasn’t real?), or to saints like Josemaría Escrivá (who founded Opus Dei, which is assuredly a cult, or so The Da Vinci Code told me), Catholics continue to find themselves very uneasy when confronted with what they perceive to be “inappropriate” devotions.

Some Catholics might even object to the practice and promotion of popular piety as a whole, arguing that they often distract from the liturgy. This very magazine published a Sounding Board (“Let’s not be so devoted to devotions,” October 2005) that took that very position: “Maybe I’m overreacting, but I do think many of these devotions indeed have the effect of returning us to a medieval model of being church,” writes Bryan Cones, who earlier notes that “devotions arose when the place of the laity in the church had been greatly diminished.”

My somewhat combative tone in the preceding paragraphs notwithstanding, I see where these conscientious objectors are coming from. I really do. After all, shouldn’t Christ be enough? Why admit anything into your life that could be distracting you from God?

But I have personally found the exact opposite to be true. Devotions, far from a distraction, have deepened my own faith in Christ immeasurably. But this was not something I stumbled upon easily. To get to this conclusion, I had to take the long way around.

Devotions, far from a distraction, have deepened my own faith in Christ immeasurably.

I left the Catholic Church when I was 17, and I stayed gone for the better part of five years. Like many young people of my generation, I had become convinced that religion was little more than an inconvenient superstition that had no place in my life. So, as one in that situation often does, I went looking for the thing I swore I did not need in all the places it probably would not be.

After numerous stops in some unsavory locales, I concluded my quest to fill the void that the church had left in a place a bit more agreeable: poetry and literature. In hindsight, it seems natural that I would end up there. Literature, as Canadian literary critic Northrop Frye points out, is often treated as a kind of “secular scripture” by many scholars of the art form, who pore over a few lines from Keats in the same way a monk would read a passage from Ephesians.

It was not long before I became one of those scholars. I would latch on to a writer and mine everything he or she had written for every last nugget of insight. Eventually, the writer to whom I found myself attached at the hip was Ezra Pound, the American poet that T. S. Eliot once called il miglior fabbro: “the greater craftsman.”

But Pound was not a great man to go to for insight. He, as I found out embarrassingly late, was a capital-F Fascist.

In 1908, ashamed of his Americanness and seeking the grandeur only the Old World could provide, Pound emigrated to Europe and eventually made his way to Italy by 1924. In Italy he found what he thought to be the true heirs of Western culture, the ones who would preserve its glory. He took up their cause, broadcasting his own handcrafted radio propaganda on behalf of the Fascist regime to American troops in Italy. Eventually, he was captured by those troops and imprisoned in an outdoor cage during the heat of the Italian summer. When he was brought back to the United States, he evaded treason charges by pleading insanity and spent much of the next 13 years in a mental hospital.

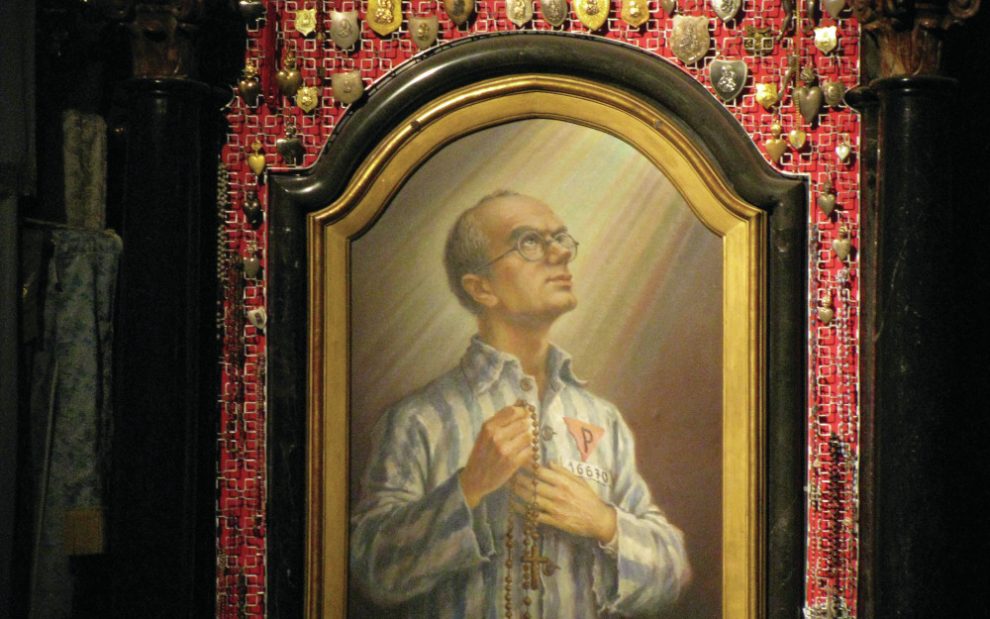

At roughly the same time, another man also found himself in Axis-occupied Europe. He also broadcast his message over the radio waves—but in the name of Christ, not Benito Mussolini. He also found himself in a cage, this one of German make, and was accused of treason, though rather than plead insanity he decided to die in the place of one of his fellow prisoners. This man was St. Maximilian Kolbe.

They were a perfect symbol of the fork in the road I thought I had bypassed years ago.

I found the story of St. Kolbe soon after I learned the uncomfortable truth about Pound, and it shook me to my core. Here were two men who were each other’s mirror image, who led eerily similar lives but who could not be more different in how they affected the lives of the people around them. They were a perfect symbol of the fork in the road I thought I had bypassed years ago. I knew I had to turn back and find my way to that other path.

Since then, I have noticed that many of my old literary and artistic idols—and idols they often were—had a similar saintly mirror, though none were as starkly different as Pound and St. Kolbe. I saw that the Franciscans were strikingly similar to the English Romantics, though without the penchant for opium abuse. It was easy to imagine how Emily Dickinson, clearly the most admirable of the bunch, might have become fast friends with St. Thérèse of Lisieux. And looking at the tilma of St. Juan Diego, I finally understood the flood of awe that overcomes so many when they look at a Mark Rothko painting.

Rather than leading us astray, devotions of all sorts keep us gently and safely penned in greener pastures. They ensure that the human impulse to revel in the natural world, in the concrete world of sensation and action, remains directed toward God. If such practices were cast out of the realm of acceptability, we would surely find our way to them anyway. And in the darkness they would become far more sinister than a statue of a saint or a set of prayer beads could ever be. Even in scripture, barely a dozen chapters after God commands the Israelites to “not make for yourself an idol” (Exod. 20:4), they set about building a golden calf to worship.

Devotional practices are one of many ways that the church echoes Christ in recognizing that creation is, after all, good.

Advertisement

We are created, embodied beings, and as such we are bound to the world of created things. In a sense, Christ’s incarnation and his institution of the sacraments were a recognition of our need not only of outward signs of an inward grace but of a redeemed creation in which God is tangibly present. We often need, like Thomas the Apostle, to reach out and touch him.

Devotional practices are one of many ways that the church echoes Christ in recognizing that creation is, after all, good. They serve as a lodestar to orient us toward what is really the best of that good, toward those places where Christ’s presence can be most readily and clearly felt. They can point us toward the cell in Auschwitz where a man prayed with his fellow prisoners, rather than the cage in Pisa where a very different man composed poetry. Without that lodestar, those two places can begin to look uncomfortably similar.

This article also appears in the March 2021 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 86, No. 3, pages 21-25). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

This article is also available in Spanish.

Image: Unsplash/Bogdan Migulski

Add comment