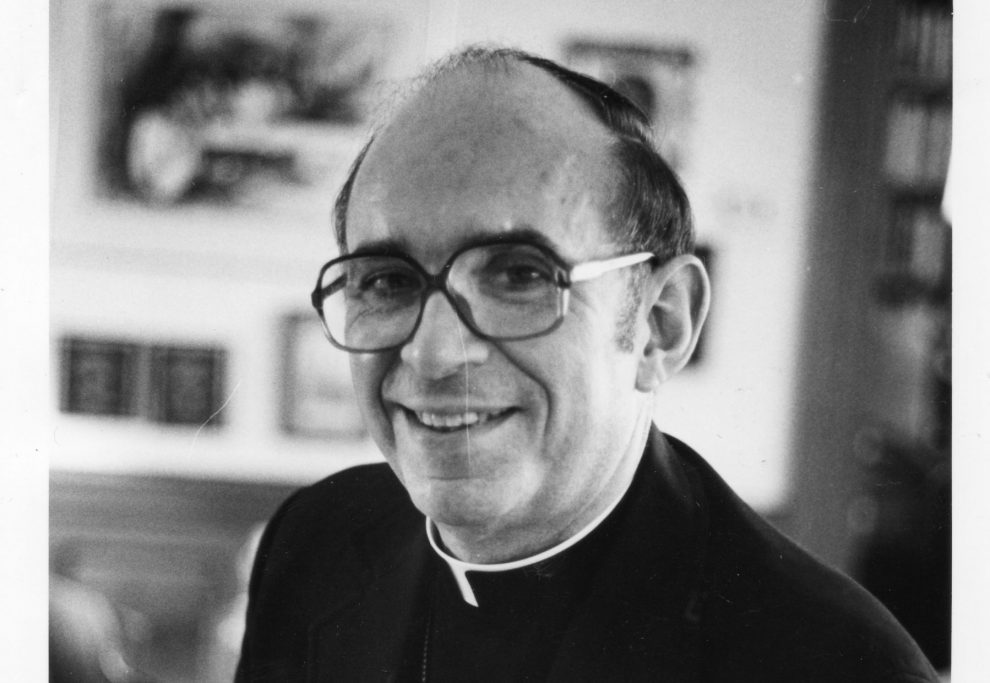

The title “prince of the church” carries with it the sound of trumpets, the flash of a ring, the image of royalty. But Cardinal Joseph Bernardin, far from playing up his royal title, has always preferred to see himself as, first and foremost, a member of the family. In one of his first Masses as Chicago’s new archbishop, Bernardin drew cheers when he told the assembled throng, “I am Joseph, your brother.”

Bernardin spends the first hour of each day praying—a decision he made after years of feeling that his prayer-life was not quite what it should be. “One of the best things about this experience is that I’ve been to share it with people. Somehow people just take it for granted that I’ve got everything put together, that I’ve never experienced the problems they’re experiencing. And when I can tell them that I’ve gone through the same thing, it gives them a great deal of encouragement, a big boost.”

Most people think a cardinal must spend a lot of time talking to God. How did you get started?

First, I think you have to know that I grew up in a situation that was totally unlike the one I’m in now. My mother and father had emigrated from northern Italy, and they moved to South Carolina because my father and his brothers were stonecutters. Columbia, the capital of the state, is near some very fine granite quarries. Other than two cousins who lived in the same house as we, my sister and I were the only Catholic kids on our block; we were also the only Italians—and probably the only ethnic family—in the neighborhood. It was a totally different environment from the ethnic neighborhoods of Chicago. Because the Catholic school was so far away, I went to the public grammar school until fifth grade.

I hardly remember my father because I was only 6 years old when he died, and he was ill with cancer for two and a half years before that. But my mother was a good, strong woman. She always saw to it that we went to church, that we said our prayers. We weren’t an overly religious family, but we went to Mass on Sundays and said our prayers.

When did you decide that you wanted to be a priest?

I never even thought of it during my high-school days. I went to the public high school, where there was hardly any focus on religion at all. Interestingly enough, though, out of 30 people in my homeroom, 4 of us became ministers: one became an Episcopal priest who’s now a bishop in South Carolina; one became a Lutheran pastor; one became a Baptist minister; and I became a Catholic priest.

During my high-school years I wanted to be a doctor, and I got a scholarship to the University of South Carolina. After one year there, I changed my mind and decided to become a priest. Nobody would believe it at first because I had never really talked about it. In the past whenever people had asked me about priesthood, I’d always say, “Oh no, that’s not what I have in mind.”

So what influenced you to make that decision?

I think it was basically a couple of parish priests whom I got to know very well. I was oriented toward some kind of service to people, but I was thinking of medicine. But through the influence of these priests, by watching their example and talking with them, I decided to go to the seminary. I had to give up the scholarship at the university, and I remember my mother saying, “If you go to the seminary and decide to leave, what are we going to do about your education?” Well, I persevered and was ultimately ordained.

When I was ordained I had the same ideals as any young person, and I worked hard at them. But I have to admit that I kept so busy I really didn’t take time to develop a deep spirituality. I remember thinking, even then, “One of these days you’re going to have to root all of this activity in a much deeper spirituality.” I wasn’t a bad person, but still it seemed that the work I was doing always took priority over prayer. That was always something of a worry to me, and I knew that eventually I would have to come to grips with it.

What finally made you do something about it?

It didn’t happen until a number of years later when I had become archbishop of Cincinnati. I suddenly began to realize that I was counseling people to do things that I myself wasn’t doing. I was calling them to spirituality and a way of life that was far beyond where I was. I remember telling myself that I had to do something about it as a matter of personal integrity: “You must try to live up to what you’re telling other people to do.”

One evening I was in a restaurant with three young priests, two of whom I had ordained. We were talking about this, and I realized that all three were further advanced than I in spirituality. They told me, “If you really feel this way, you should do something about it.” I thought at the time it was kind of strange that these three younger men were telling me, the bishop and the older person, what I should be doing!

I made a decision that I would make the development of my spirituality a priority in my life, and that that would be the foundation for my ministry to people.

In any case, I made a decision then that I would make the development of my spirituality a priority in my life, and that that would be the foundation for my ministry to people. Without it, I knew that I would just begin to dry up after a while. That was really a turning point in my life—it was about eight years ago.

What changed after that?

I found that my most precious commodity was time—the thing I had the least of. Nonetheless, I decided that I’d give the first hour of my day to God, no matter what my schedule might be—that I would get up early enough to spend that hour in prayer. And I’ve tried to do that ever since. Starting out the day that way has made a big change in my life. I haven’t become an introvert. I’m still as active as I was, but I really feel the need for this quiet time with the Lord. It changes my whole perspective. I find that throughout the day I’m praying more than I did previously.

One of the best things about this experience is that I’ve been able to share it with people. So many who are spiritually hungry come to me; they want to enter into a close relationship with the Lord, but they don’t know exactly how to do it. Somehow when people come to me, they just take it for granted that I’ve got everything put together, that I’ve never experienced the problems they’re experiencing. And when I can tell them that I’ve gone through the same thing, that we’re all pilgrims together, it gives them a great deal of encouragement, a big boost. One of the things in my life that gives me so much strength is the way people open up to me and tell me about their lives, their own journeys. Now I’m able to share my journey with them. That’s been terrific.

What about specific forms of prayer? It seems that some people feel very cut adrift because the family rosary of their childhood may not comfort them any longer, but they’re not comfortable with the newer forms of prayer either. A lot of people, when they’re caught by that confusion, just stop praying altogether. And God seems very far away.

One thing that has changed in my life is that I no longer see God as someone who is “way out there.” I think more in terms of God being a part of our daily lives. We encounter him in prayer; but we also encounter him in our relatives, our friends, and many other people whose lives we touch in some way. I always tell people to pray in they way they feel most comfortable. What works for one person may not work for another. My understanding of the rosary, for example, has changed a great deal over the past few decades.

How?

When I prayed the rosary in earlier days, it was highly mechanical; it was almost an end in itself. That’s obviously not the way it should have been, but that’s often how it was for me. I’d rush through it, or I’d say it very mechanically.

In the last few years, however, I found that I often became distracted during prayer. I discovered that it was helpful to have the beads and a set prayer, that these things helped bring what I was doing into focus. The purpose of the rosary for me now is not so much to say the set prayers over and over again, but to give me an opportunity to reflect on the Lord and the specific events in his life which have so much importance for the church and for my own personal life. It was also a matter of looking for help, for a crutch. And then I found out that the rosary is a very good help. I saw it in a different light, as a means to an end, as a way of helping me to pray.

Do you consider it mainly a Marian devotion?

There’s a Marian dimension to it, obviously. But it’s also a Christ-centered devotion, and it always has been. I have no problem bringing those two together.

Is the rosary for everyone?

Again, I feel that everyone needs to find the ways to pray that best suit him or her. But we should never be ashamed to admit that some of the old forms of prayer really work; we don’t have to be committed just to the newer forms of prayer—shared prayer and all the other forms which I enjoy very much. I personally use the newer forms together with some of the older forms.

God reveals himself to us in so many different ways—in prayer, in the celebration of the sacraments, but also in the daily lives of people. If you’re constantly looking for God elsewhere, I don’t think you’ll ever find him. If you’re willing to find him here and now—in the present circumstances of life—then your chances are much better.

How do you achieve that deeper prayer life? I’m sure that so many people have made a decision to “do it right,” to really spend time in prayer. And all of a sudden they find themselves sitting there saying, “Okay, now what?”

I went through life doing that very thing. I’d go to a retreat or Lent would come along, and I’d make all kinds of promises. Then a few weeks later I’d realize I wasn’t doing anything about it. Real change comes about only when you make a serious commitment. Unless you make that commitment, you’re going to forget about the promises. But with God’s grace and the help of other people, you can keep your commitment to change.

What’s the minimum daily prayer requirement for the average Catholic?

Really, I don’t think I can give any hard and fast rule. There’s no “right” amount; there’s no right or wrong way to pray. I spend the first hour of my day in prayer, but if I were a married man with a family I’m not at all sure I’d be able to do that. The demands on my life are very different from those of other people. In the final analysis, what’s really important is to spend time with God. Maybe that can be done in a few seconds, or maybe it takes longer.

What about listening to God? Where do you hear God best?

That’s hard to say. God talks to us in so many ways. He talks through the Scriptures, for example; commitment to God’s word should be very much a part of our spiritual life. But God speaks in many other ways as well—in the events that occur from day to day. Part of prayer is simply reflecting on what has been happening to us, the ways in which God is talking to us through our life experiences, through things that other people have done or said. So prayer is not just talking; it’s listening, too.

I also have to say that sometimes prayer is better than at other times. Sometimes, when you try too hard, you realize that you’re daydreaming or problem solving. That’s okay. The important thing is the continued desire to spend time with the Lord, even though nothing much seems to be accomplished. The desire will keep you going.

Do you pray to one particular person of the Trinity?

I focus on different persons at different times. I find, though, that usually I focus more on Jesus. Somehow I can relate to him a little better. He is one of us, and we know more about him in the Scriptures.

Do you feel that Jesus is watching you or listening to you when you pray? Is he up in heaven watching 4.5 billion TV monitors to see how we’re doing or whether we’re praying enough?

I don’t think I’d put it quite that way.

Neither would I, exactly. But it’s hard to visualize how prayers are heard. Do you think Jesus listens when you pray?

I think so, yes. If I felt that God was not present to me when I prayed, then why would I do it? I’m not going to spend time engaging in make-believe. My faith tells me that God is with me when I pray, and I believe that with all my heart and soul.

If I thought God was so distant that he couldn’t be part of my life, then I would probably not try to share my life with him. For me, it’s as simple as that. But that doesn’t solve all the problems. I do believe that God is present to us in many little ways. Traditionally we have thought of God as a distant person; we prayed to him, we looked up to him. That’s okay. But God is also present among all of us, here and now. He’s present in this conversation we’re having. He’s a silent partner. If I didn’t believe that, I’m not at all sure that I could be as committed as I am to God, to the church, to my ministry.

You mentioned that prayer shouldn’t be just problem solving. But if part of prayer is listening, what is it that you listen for? Isn’t it solutions to problems?

Maybe I overstated it. I find, though, that when I’m sitting there in the quiet of my room, I start thinking about all the things that are going to happen during the day. Should I write a letter to so-and-so? If so, what should I say? And I think about all kinds of other problems. That kind of problem solving doesn’t really touch at the heart of prayer.

Prayer can obviously be a great help in discerning the direction you should take with your problems, in dealing with the challenges of your life. Maybe that is a kind of problem solving, but it’s very different from mentally dictating a letter or deciding how you’re going to tell someone off. You’re always going to worry about those things to a certain extent, especially if you’re a worrywart as I am. But as you develop spiritually, you probably become less concerned about those details, and you focus more on what’s happening in your life and the direction you’re heading.

What about praying through a particular saint, asking that saint to intercede for you?

It’s all a question of balance. The Second Vatican Council certainly reaffirmed the value of intercessory prayer. That’s part of our tradition, and I believe in it. But at the same time, there have been excesses where intercessory prayer or devotion to the saints began to take precedence over our devotion to the Lord and to the Eucharist. While saintly devotions have a very important place in our tradition and in our spiritual lives, they have to be seen in perspective; they shouldn’t edge out the more essential parts of our faith.

What does it mean to pray about God’s will? If I pray for someone with cancer to be healed, should I instead be praying for God’s will to happen, whatever it might be? Can I ever pray for the Cubs to win the pennant?

Well, I don’t normally pray that a team will win.

Even within the diocese?

At least I never admit it.

I tend not to pray for specific outcomes; rather I try to pray that there will be a good outcome, whatever it might be. For example, I have my litany of things that I pray for in the morning. Most of them have to do with problems in the archdiocese, and, frankly, I don’t know how these problems should be resolved. But I pray that I will have the strength, the integrity, and the patience to deal with them in the best way possible. That’s what I pray for.

Where do you get that attitude? Is it a gift from God, or do you supply it yourself with a “positive mental attitude” approach?

It comes both ways. There is a personal dimension, but I also think it’s a grace. One difficulty is that sometimes we place too much of a burden on God. We have to so our share. I see prayer as helping in that collaboration between me and God. We pray for strength, as Paul did in his epistles. But then we have to do our part. We can’t shift the burden totally onto someone else, whether that be God or the saints or whoever.

Doesn’t that sometimes lead to an “I’ve got to save the world” mentality?

I don’t want to take back what I just said—that God expects us to do our part. That’s why he gave us a mind, a will. We have to think. We have to decided things. And we can’t use religion or prayer as a way of copping out.

At the same time, we are not gods ourselves; and we have to have enough faith and trust to believe that somehow, in God’s providence, things will work out. Let me get very personal. Chicago is a huge archdiocese, and it’s very diverse and complex. There are many wonderful things happening here, but there are also many problems. The biggest mistake I could make would be to think that somehow the resolution of all those problems depends totally on me, that I have to be responsible for every thing that happens. If I were to do that, first of all it wouldn’t work. Second, I would end up as a basket case.

One thing that has changed in my life is that I no longer see God as someone who is “way out there.” I think more in terms of God being a part of our daily lives.

Therefore I have to trust. I have to trust at the human level—trust other men and women in the archdiocese, in the parishes. But I also have to trust in God. To be perfectly honest, if I didn’t have that kind of faith and that kind of trust, I wouldn’t be doing what I’m doing. I wouldn’t be in this job.

If I had to cross every “t” and dot every “I” in my own life every day, I’m not sure I would survive or succeed. I have to constantly tell myself that there is a God. He put me here for a purpose. I believe that he will help me and give me the grace that I need, even though at the moment I don’t see all the answers. Rather than getting hung up on myself, I’m going to rely on God and trust in him.

Do you ever find God calling to you to do things you don’t want to do?

Yes, yes.

And you find yourself being pulled in directions that you’d rather not go in?

Yes, definitely. For example, some of my critics think that I get a great deal of enjoyment out of all the things I do. But this is not true. I’m human like everyone else, and I don’t like being kicked around or criticized. Yet I know that if I address certain issues, I’m going to catch it from all directions. Sometimes I have to deal with things on the agenda of the more conservative segment of the church. At other times, I address matters that are more the concern of the liberal wing. As a result, I get hit by both sides.

For example, I’m willing to stand up and be counted on the question of abortion; and I’m criticized for that by some people. But I’ve also taken stands on war and peace and justice, and I’m criticized for that. Some people seem to think that each day I decide what particular issue I’m going to address, and then I go after it with great joy. That’s simply not true. There are times when I’d just as soon not get into the public fray or be part of the debate, and yet I feel that I have to. Sometimes I would personally like to sidestep an issue, but I feel a responsibility to address it. I think that’s true of all of us. You’d like to pick your fights. But sometimes you don’t have that choice, if you’re going to carry out your responsibility.

Do you ever feel that sometimes you’d like to just go to Mass and sit in the pew?

Sure I do.

Do you ever get tired of the need to be cautious and careful about everything you say?

Sure, but that’s part of life. That’s not only a problem for me as a bishop. Everyone faces it in their families and in their work. Of course I’d like to be free as a bird, and at the same time have the assurance that every initiative of mine will be in total accord with God’s will and the teaching of the church. But that’s not the way it is. I have to struggle, I have to listen and learn, I have to be careful that I don’t betray the trust that has been placed in me.

How can someone try to “imitate Christ” when our lives are so different from his?

For me, imitating Christ means living out in our lives the values that he witnessed to. But I don’t think that happens only by learning about those values. More than knowledge is needed. People will accept the teachings of Christ only if they have first accepted Christ. There has to be a conversion; when that happens, the person is more disposed to live out in his or her life the values that Christ taught. Take the topic of sexuality, for instance. I happen to believe that the church’s teaching about sexuality is correct. But if you approach sexuality simply as a laundry list of do’s and don’ts, you won’t get anywhere.

Maybe in the past, authority counted for something; but you know as well as I that few people accept things solely on the basis of authority anymore. So instead we have to focus on values. What is the value behind this “do” or “don’t,” and does that value make any sense? In terms of motivation, in terms of wanting to do the right thing and live out the right values in your life, that’s only going to happen if you’re really committed to the Lord, if you have experienced some kind of conversion to him. When that happens, you’ll often find that the demands he makes are far more radical than some of the institutional do’s and don’ts.

When does that kind of conversion happen? During dramatic encounters with the Lord? During something as tried-and-true as the sacraments?

All the sacraments are encounters with the Lord. While I don’t deny that God can work independently of the sacraments, they are his gift to us; they were given for our benefit. I think God gave them to us because we’re all looking for tangible signs. We need to hear and see and feel things. The sacraments have a human dimension that’s extremely important.

Some people say they can deal directly with God, and that they don’t need the sacraments to intervene. We hear this often about Confession, for example.

Sure, people can deal directly with God. But we also believe that the Lord did establish a church, and that the sacraments were part of his gift to his church. Why not use the gifts we were given?

Do you have any models for your spiritual life, people whom you’ve patterned yourself after?

In terms of my ministry as a bishop, two people stand out. One is Archbishop Paul Hallinan, who was my bishop in Charleston and later in Atlanta. He was an extraordinary person, and I really attribute a lot to him. He taught me one thing that I’ve never forgotten. I remember that on one occasion we were dealing with a big problem. He said, “Joe, we’ve got to do it his way because it’s a matter of principle.” Six months later a similar problem arose, and he thought it should be handled differently. I said, “But Bishop, I thought you said this was a matter of principle.” He looked at me with a smile and said, “Joe, there are times when you have to rise above principle.” Of course, that’s not all or even the main thing I learned from him, but that’s not bad!

The other person, who’s still a close friend, is Cardinal Dearden. I’ve learned a lot from him too.

But I’d also like to say—and I hope you don’t think this is just rhetoric because it’s not—that there are so many people I come into contact with, men and women, who impress me very much. At times they really humble me. There are so many people out there who are better than I, who live good lives, sometimes at great cost to themselves. I see these people. I talk with them. They write to me. These are the people who keep me going each day.

Part of prayer is simply reflecting on what has been happening to us, the ways in which God is talking to us through our life experiences.

I guess it’s the nature of my job to hear about the complaints—generally people don’t come to me unless they have a problem. The mail just piles up each day; sometimes I have the feeling that hell must be a big post office, where you are constantly working with stacks of mail that are always replenishing themselves. Anyway, I have to deal with a lot of nonsense in this job, as people do in every job. The most encouraging thing is that there are so many good people, people who are living good lives, shaping their lives according to the message of Jesus. It’s very inspiring, and it really gives me a great deal of courage and motivation to talk with these people and listen to them and have them share their lives with me. It keeps me going.

If you could tell every Catholic in the country just one thing, what would it be?

I do have a message that I try to stress in my homilies, in my personal contacts with people. I don’t know how successful I am, but the general thrust of what I try to say, whatever the form, is that God really loves you. You are very important—no matter how mixed up you might be or think you are, no matter what difficulties you may be facing, no matter how hopeless the situation might seem to be. You are very, very important, and the Lord loves you. And you must not forget that. If you really believe that, then a lot of the other problems will be worked out without too much conflict or worry.

I believe that with all my heart and soul, and I really feel sorry for people who don’t believe that. Some people may say that God loves them, but they really don’t believe it in their heart, in the way they live their lives. This results in so much tension and unrest: parishioners fighting among themselves, religious who are upset about one thing and priests who are upset about another. And all this is in the name of religion! Sometimes I wonder, do they really believe that the Lord loves them and will help them? He will show them the way; he will shower good things on them if they give him a chance. But if you’re constantly fighting, you make that impossible.

I think what people are looking for from their ministers today—both ordained and unordained—is the assurance that God is present and that somebody loves them and cares for them. People don’t expect to have priests or ministers answer all their questions or solve all their problems. Either they already know the answer but somehow can’t make it a part of their lives, or they know the minister doesn’t have the answer; so what’s the use of pretending? Rather, people are looking for the kind of presence that assures them that they’re not alone, that they’re not going to be abandoned. They’re looking for someone to pray with them and hold their hand, both literally and figuratively.

Even when I don’t have a chance to talk to people, I try to communicate that message. I stand in those receiving lines until I’m blue in the face. What I try to convey to people is that somebody does care. You know, you can do that even if you don’t have time to use many words. Sometimes I think the words get in the way.

This article was originally published in the September 1985 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 50, No. 9).

Image: From the USC Archives

Add comment