Autumn is St. John Henry Newman’s time of year. Newman was canonized October 12 and his feast day is October 9. But the fall foliage also reminds me of Newman.

During a hike with a friend in the autumn of 1839, Newman looked out over the foliage and said, “a vista has opened before me, to the end of which I do not see.” He was speaking of the next and most dramatic step in his intense spiritual journey: finding his home in Holy Mother Church. We rightly hear melancholy echoes in these words of the sacrifices that he eventually had to make, leaving his beloved Oxford and facing the disdain of many of his friends.

Newman’s words as he looked out at the changing leaves also spoke of the deeper spiritual essence of his journey. This great modern saint, who Newman expert Father Ian Ker calls “the doctor par excellence of the post-conciliar period,” spoke over and over of “the invisible world.”

An open-ended vista of saints, angels, and the Holy Trinity continually burst upon Newman, growing in intensity as he journeyed on his earthly pilgrimage. Newman merged more completely into this invisible world through deeper communion with the church and God’s creation that surrounded him, such as the trees on that fall day building to their autumnal peak.

Newman’s view of the church is well known. His “Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine”(1845) provided an innovative big-picture theology of the church and its obvious changes over the centuries. These changes were not corruptions or arbitrary, Newman argued, but the organic unfolding of an idea over time analogous to the growth of a river from a spring. Like a river, the church is “more equable, and purer, and stronger, when its bed has become deep, and broad, and full.” Newman’s theology of development culminated in in his own life when he took a highly unusual step for a 19th-century Englishman and entered the Catholic Church that same year.

We know much less about Newman’s view of Nature (his own practice was to always refer to Nature with a capital “N”). Modern dualism is so ingrained in us, reducing the natural world to empty clay in our increasingly robotic hands, that we don’t think to look.

For Newman, trees couldn’t be more spiritually alive.

But for Newman, those trees couldn’t be more spiritually alive. Indeed, the trees and all of Nature are participants in the angelic hierarchy, an order now so foreign to most of us that we don’t even know that we’ve lost it.

Newman explained what he meant in “The Powers of Nature,” a sermon delivered on a similar fall day in 1831, asking questions that we all have but seldom think through theologically: “Why do rivers flow? Why does rain fall? Why does the sun warm us? And the wind, why does it blow?”

Modern thinkers give no direct answers to these questions, merely use impersonal and self-contained “laws” to describe what they do.

Not surprisingly, this answer wasn’t sufficient for Newman. He turned to scripture and tradition of the church and found angels at work in the rivers and the winds, saying, “Those wonderful and vast portions of the natural world which seem to be inanimate” to the secular mind are moved by “Spiritual Intelligences.” Newman continues: “The course of Nature, which is so wonderful, so beautiful, and so fearful, is effected by the ministry of those unseen beings. Nature is not inanimate; its daily toil is intelligent; its works are duties.”

St. John Henry Newman’s point about Nature animated by Spiritual Intelligences can’t help but strike most of us as strange. Like the good modern people we are, we usually only see the angels that come from “outside” the world to deliver messages or perform a singular deed. Our individualistic tendencies restrict those that live in the world to guardianship. Knowingly or not, we leave the rest of Nature to flat and mechanical “laws.”

Sure, some of us resist the reduction of the natural world to empty material. We usually point out that the Holy Spirit infuses all. All things are created and sustained by God’s love. We are certainly not wrong.

The course of Nature, which is so wonderful, so beautiful, and so fearful, is effected by the ministry of those unseen beings. Nature is not inanimate; its daily toil is intelligent; its works are duties.St. John Henry Newman

Newman agrees but adds something more. His view of Nature has the same personalism that so beautifully infused all his theology, summed up in the motto he chose for his cardinal’s coat of arms, cor ad cor loqitur—“Heart Speaks to Heart.”

For Newman, theology was not a system of abstract ideas but living connections between beating hearts. These connections are shaped by the agency of free human beings and ordered and sustained by the love of the Sacred Heart.

Nature is ordered in the same way through angels. Living, created beings with will, intelligence, and emotion—“hearts”—act within the rivers that flow and wind that blows.

The contrasting views of God are stunning: not the impersonal and increasingly exiled clockmaker of the Deists but an immanent creator intimately permeating every corner of this vast and dynamic cosmos through “the agency of the thousands and ten thousands of His unseen Servants.” Not only a single blazing sun below the horizon but also uncountable stars shimmering in the darkness, the beating hearts of Nature dancing to the music of the Holy Trinity.

What about science? Newman, of course, affirms it but orders it in its proper place. Science provides general principles that allow us to better use God’s gifts “to the benefit of man.” This is about practical use, however, and not about how nature really works.

No one should fool themselves into thinking that the “miracles of Nature” are “mere mechanical processes, continuing their course by themselves” and that Nature “does not hear him, and see how he is bearing himself towards it,” Newman believed. If the Christian denies the reality of Spiritual Intelligences and adopts the secular vision of the mechanical world “what a poor weak worm and miserable sinner he becomes!”

Angels animating the created order may seem strange to our increasingly digitized minds and perhaps easy to gloss over. St. Pope John Paul II, who in 2001 called Newman a “sure and eloquent guide in our perplexity,” would urge us to join Newman in re-traditionalizing our view of Nature.

For Newman, theology was not a system of abstract ideas but living connections between beating hearts.

In his 1986 Catechesis on the Angels John Paul II explained that “the angels take part, in a way proper to themselves, in God’s government of creation, as “the mighty ones who do his word” according to the plan established by Divine Providence.”

He adds that angels might be “denied also by materialists and rationalists of every age but, as a modern theologian acutely observes, ‘if one wishes to get rid of the angels, one must radically revise Sacred Scripture itself, and with it the whole history of salvation.’”

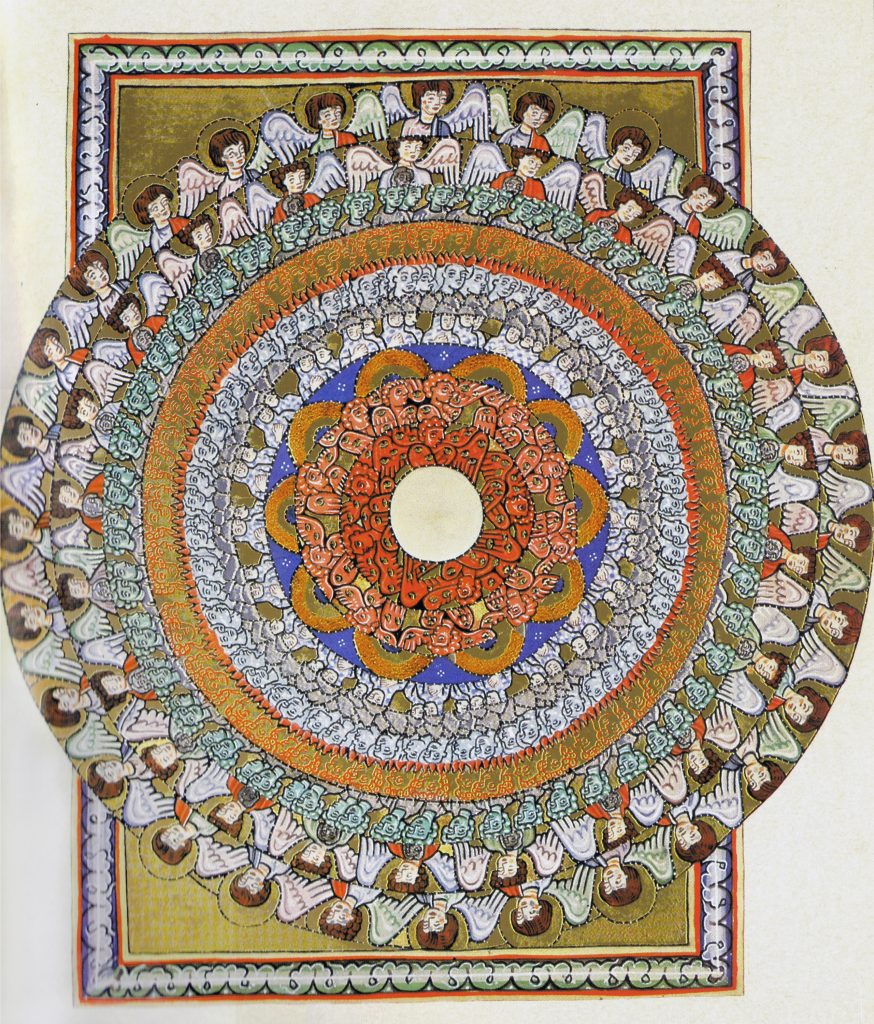

Indeed, though foreign to us it is here that Newman is at his most orthodox. The ancient teaching of the church fathers is that angels not only inhabit every aspect of the Earth and sky, they are its living energies and personalities, something that St. Thomas Aquinas affirmed in the Summa and St. Hildegard of Bingen captured in art.

Newman recognizes that some may call angels moving the river and blowing the winds fanciful, “but if it appears so, it is only because we are not accustomed to such thoughts.”

Scripture teaches about the angels for practical reasons and nothing is more practical than connecting the visible world to the more important invisible world. “Nor one more consolatory; for surely it is a great comfort to reflect that, wherever we go, we have those about us, who are ministering to all the heirs of salvation, though we see them not,” says Newman.

This autumn, look around you. As the leaves transform—or better said, transfigure—in glory, ask for Newman’s intercession to help us see the invisible world that radiates out through them.

Spiritual Intelligences are everywhere: “Every breath of air and ray of light and heat, every beautiful prospect, is, as it were, the skirts of their garments, the waving of the robes of those whose faces see God in heaven.”

In the colors the Hearts of Nature take up the hymn that the heavenly hosts sang at the birth of the Savior: “Let all the trees of the forest rejoice before the LORD who comes” (Ps 96:12–13).

St. John Henry Newman, open to us the vista that has no end, that we may know the hearts of Nature, servants of the Sacred Heart who orders and sustains all in God’s love.

Image: Unsplash

Add comment