Read

The Least of These

By Carla Swafford Works (Eerdmans, 2020)

“The apostle Paul does not have a reputation for caring about ‘the least of these,’ ” writes Carla Swafford Works in The Least of These: Paul and the Marginalized. The message in her book, however, is that Paul showed a preferential option for the poor and the marginalized.

Paul’s view on slavery has received mixed reviews in Christianity. But Works reveals that in his letters Paul recommends a change of status from slave to brother for Onesimus and asks Philemon to lower his status from master to brother. In this way, Paul teaches that any household that claims Christ as Lord must embrace the oneness that believers share in Christ.

Likewise, Paul’s view on women remains a hot button issue in scholarship. Although this book admits to his complex view on women, readers will learn that, notwithstanding passages like 1 Corinthians 14:34–35, there is overwhelming evidence in Paul’s letters of women occupying leadership roles in the church. Works also argues that Paul’s recommendation that women should cover their heads in church was countercultural: Head-covering was a mark of a woman’s dignity and respect, and Paul wished that women of every status in the Roman Empire be treated with the honor reserved only for a class of Roman women.

Paul enjoyed social standing, yet he imitated the service and humility of Jesus. Not only did he preach the gospel to those on the margins, his lifestyle also placed him in the category of the “least” in the empire, such as the Galatians to whom he preached the message of unity in Christ.

Overall, The Least of These insists that Paul’s ministry was congruent with Jesus’ ministry, because God is working through both to break down the barriers that separate humankind according to race, sex, gender, social status, and economic status.

—Father Ferdinand Okorie, C.M.F.

Holy Troublemakers and Unconventional Saints

By Daneen Akers (Watchfire Media, 2019)

Every once in a while, a book comes across my desk that I can’t bear to send away to a reviewer. Holy Troublemakers & Unconventional Saints is one of those books.

Written for a young audience, the book offers brief biographies of 36 people of faith working for justice. Each chapter offers vocabulary words and reflection questions geared toward elementary readers.

While even adults will find the stories compelling and well written, what caught my eye was the art. More than two dozen artists contributed to the volume. Some, such as iconographer Kelly Latimore, may be familiar to readers of this magazine. Others are lesser known. Together, the images and stories result in a book that is a piece of art as much as it is a children’s book.

Author Daneen Akers wrote the book, which was made possible through a crowdfunding campaign, after she struggled to find faith-based materials to share with her daughters that didn’t “only show a narrow type of Christianity.” She wanted her daughters to be exposed to a wider range of religious faith, people of faith whom she refers to as “troublemakers for the higher good, people who know that some rules need to be broken to make our society work for everyone, especially those who are most vulnerable.”

Akers’ collection reaches across gender, geography, historical era, and religious tradition. Well-known religious figures such as St. Francis of Assisi and Gustavo Gutiérrez appear next to other historical figures such as Florence Nightingale and Mister Rogers and modern figures such as Kaitlin Curtice, a Potawatomi and Christian writer and activist.

Akers makes a point of including a wide range of identities: women, LGBTQ people, Muslims, Jews, indigenous peoples, disability activists, and more. The result is a book that is a joy to read for people of all ages.

Writing Straight with Crooked Lines: A Memoir

By Jim Forest (Orbis Books, 2020)

In this memoir, Forest looks back on his conversion from atheism to Christianity, his peace activism during the 1960s, and his encounters with Dorothy Day, Thomas Merton, and Daniel Berrigan.

The Caregiver’s Companion: A Christ-Centered Journal to Nourish Your Soul

by Debra Kelsey-Davis and Kelly Johnson (Ave Maria Press, 2020)

This practical self-care resource written by the founders of a parish-based support group includes journaling exercises and readings to help caregivers manage daily challenges.

Your Blue Flame: Drop the Guilt and Do What Makes You Come Alive

by Jennifer Fulwiler (Zondervan, 2020)

Catholic comedian, radio host, and mother of six Jennifer Fulwiler offers advice on rekindling your energy and tapping into the talents that make you unique.

Listen

Saint Cloud

Waxahatchee (Merge Records, 2020)

Waxahatchee is a creek that runs near Birmingham, Alabama. It’s also the pseudonym of singer-songwriter Katie Crutchfield.

In recent years I’ve checked out new Waxahatchee music solely because of that name, which seems to promise roots in a place and tradition, but what I heard always sounded like abstract, indie navel-gazing.

The new Waxahatchee album, Saint Cloud, is different. The lyrics are still on the abstract side, but the songs jump and swing. Southern-soul guitar riffs and melodies flow like, well, a creek cutting its way through the red clay hills around Birmingham.

The sense of wonder and joy of discovery in Crutchfield’s voice make me stop caring what exactly she means by a “speck in the oxbow.”

In promo interviews, Crutchfield credits her newfound sobriety for the record’s sounds and themes. There’s a theory in recovery circles that the emotional development of an alcoholic stops when the drinking starts and resumes only when they get sober. Something like that seems to be happening here with Crutchfield’s 31-going-on-17 return to her Southern origins.

And some of this does come through in the lyrics. “Witches,” for instance, celebrates her recovery and calls out by name the female friends who keep the singer straight. But the song that has me waiting for the next Waxahatchee album is her trip down Birmingham’s “Arkadelphia” road, past the trailer park and the roadside fireworks and produce stand to visit an old friend nearly buried in the sorrows of addiction. The details are sharp, and the chord changes and melody sound as old as the Alabama hills.

On this record we can hear an artist that knows who she is and where she’s from, and that’s always where the good stuff starts.

Watch

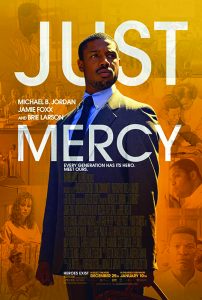

Just Mercy

Directed by Destin Daniel Cretton (Warner Bros. Pictures, 2019)

Adapted from notable attorney Bryan Stevenson’s acclaimed, eponymous 2014 memoir, the powerful, immersive film Just Mercy opens in 1986 in Monroeville, Alabama as 45-year-old African American Walter McMillian (Jamie Foxx) employs a rope to clear trees.

His adulterous affair with a married white woman provokes the local police’s ire. Encountering a police roadblock on his way home, McMillian discovers he’s suspected of 18-year-old white woman Ronda Morrison’s murder.

McMillian was then held on death row for 15 months prior to his trial. He received a death sentence in 1988, despite numerous witnesses testifying he was at a church fish fry when Morrison was murdered.

When new-to-Alabama Bryan Stevenson (Michael B. Jordan) suggests he can get McMillian’s conviction overturned, McMillian doesn’t believe the Harvard-educated lawyer knows what it’s like “down here,” where African American men are “born guilty.” But Stevenson, of rural Delaware, reassures him: “I know what it’s like to be in the shadows.” Stevenson works to challenge the testimony of dubious convict Ralph Myers (Tim Blake Nelson).

Viewers won’t get the rope off their minds. It aptly symbolizes legalized lynching, which Stevenson, as director of Montgomery’s Equal Justice Initiative, has fought—more successfully than most—for more than three decades. Singular among American feature films about capital punishment, Just Mercy is an apposite tribute to an exceptional man.

Add comment