If you’re a regular consumer of media, you’ve surely reached your saturation point of hot takes on the cultural implications of the novel coronavirus. Within the first month of lockdown restrictions, we heard from those who committed themselves to self-improvement—taking free courses from Yale, planting victory gardens—and from those for whom this can’t be anything but a time of survival. We heard from parents grateful to have more time at home with their children and from parents who would eat glass to get their kids back in school. We read about loneliness as a secondary pandemic and how we are finally checking in on our neighbors again.

Has there been any stone unturned, any possible angle unexplored, when it comes to how we are experiencing this collective crisis and how it might change us?

I appreciate the humility of writers who have been able to sit, however uncomfortably, with unknowing—those who haven’t rushed to make a plan, prediction, or recommendation beyond the present moment and those who have cautioned us against trying to pronounce an outcome for an experience we haven’t yet fully digested. I’ve been hesitant to publish any words about the pandemic for fear that I’d later have to eat them.

The news changes as frequently as my own emotional weather. With every Twitter refresh there is something new I hadn’t thought to worry about, a blind spot in my own experience that I would never be able to speak to.

The simple fact is that we don’t know. We don’t know where we’re going or how this experience will change us. We are all in the strange position of being forced to abandon our wills to providence—which is, as I learned in Jean-Pierre de Caussade’s spiritual classic, Abandonment to Divine Providence, the key step on the path to spiritual maturity. It is also how one becomes a mystic, and I’ve found the classic writings on mysticism to have a new relevance to my daily life in lockdown.

For example, I have found myself repeating a favorite prayer cribbed from Flannery O’Connor’s A Prayer Journal (Farrar, Straus and Giroux): “Oh Lord, I am saying, at present I am a cheese, make me a mystic, immediately. But then God can do that—make mystics out of cheeses.”

I wonder if a pandemic might also do the trick.

Evelyn Underhill, one of the greatest teachers of mysticism, points out in slightly different terms in Practical Mysticism, her most accessible work, that under extraordinary circumstances even the greatest cheese may become a mystic. A mystic is, in simple terms, someone who is in touch with eternity. Imagine how time distorts when you experience a death in the family, a long illness, a house fire, a war. Sometimes the occasion is happier, like when we fall in love or experience a rapturous moment in a scene of natural beauty. But more often than not, we are like a character in one of O’Connor’s stories. A violent action is the only thing that shakes us awake to the reality of eternity and our place in it. But how to maintain that stance? “The doors of perception are hung with the cobwebs of thought; prejudice, cowardice, sloth,” writes Underhill. A practical mystic doesn’t rely on “fleeting and ungovernable” experiences to blow away the cobwebs. A practical mystic trains her perception and will. She orients her heart to eternity.

The first step toward mystical practice has been made for me. My attention has been restricted, my movements confined. Faced with the suddenly undeniable reality of being unable to direct my own fate or the fates of my children, I have been forced into a mystic’s stance—which is not one of self-improvement or cleverness but of unknowing. “I do not require you now to meditate on [God] or raise various conceits, nor to form great and curious considerations with your understanding,” St. Teresa of Ávila told those who wished to learn her mystical ways. “I require of you no more but to look on [God].” A mystic is a patient observer of what already is—and what is, Underhill says, is God.

Yet mysticism doesn’t require inactivity and is not the province of “idle women and inferior poets,” as Underhill anticipates the objections of her challengers. She says, “The active man is a mystic when he knows his actions to be a part of a greater activity.” The pandemic implications are clear to me: We have become aware that staying home alone unites us in a common cause and that our private actions and mundane choices have meaning beyond our own daily lives. They always did, of course, and to believe so is part of having religious faith. But our attention has been turned by the novel coronavirus to, as Underhill writes, “new levels of the world.” A mystical moment is upon us, whether we’d have it or not.

So I have undertaken during this period of staying at home to, as Underhill put it, stand back and observe the furniture: that which was always there but has been overlooked because of my preoccupations, anxieties, and busyness. Can I work, then, to take the next steps according to Underhill—to recognize and simplify my affections, to reorient my heart?

While I was resolving to use isolation and the new, strange elongation of time to become more mystic, less cheese, I received an edition of Michael Wright’s Still Life, a weekly newsletter on art and spirit. Wright is an art enthusiast in the best sense of the word, and Still Life is his way of amplifying the best work engaging with spirituality, including projects he encounters in his work at Fuller Theological Seminary and Bridge Projects in Los Angeles. In this edition, he too was contemplating what Underhill might offer us in the time of the novel coronavirus.

He has been noticing, for starters, his neighbors. “We were all rushing past each other before, but now that we have to keep our distance, it’s like our vision sharpened. We see that six feet between us more clearly and remember the ways we used to cross it,” he writes. He has also decided to learn the names of the plants in his neighborhood. “Just like our neighbors, the purple sage and common lantana, the sweet alyssum and morning glory—they were all there, drifting past my inattention.” He quotes Underhill: “For lack of attention a thousand forms of loveliness elude us every day.”

Maybe the path from cheese to mystic is as simple as that and not at all as violent as I had assumed. Maybe all that’s required, as Michael Wright notes, is a “basic posture of openness to life that’s as accessible as the next name you’ll learn.”

This article also appears in the July issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 85, No. 7, pages 36-37). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

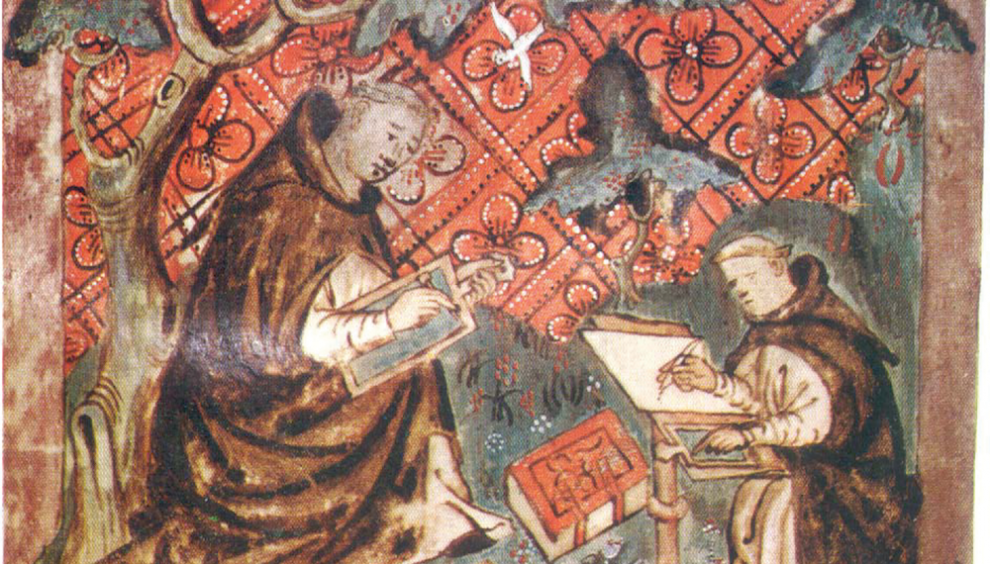

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Add comment