On March 26, 2015, the U.S. Postal Service issued a collection of stamps honoring the art of Martín Ramírez. At the time of his death, in February 1963 at California’s DeWitt State Hospital, such an accolade would have seemed like a dream.

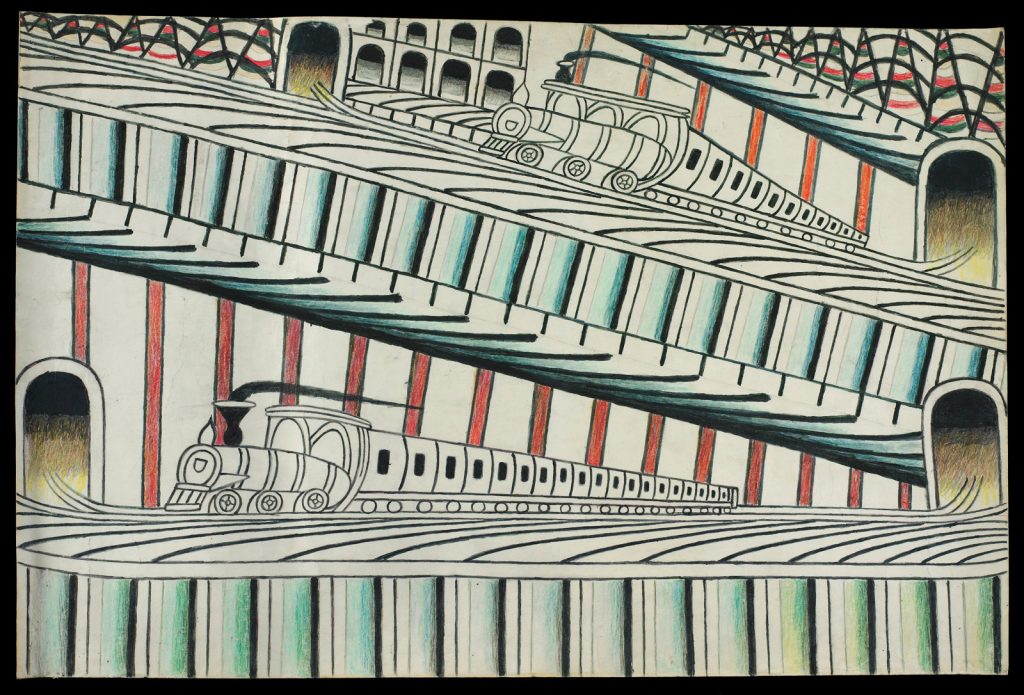

Ramírez spent the last 30 years of his life in state hospitals with what was diagnosed at the time as “dementia praecox (schizophrenia), catatonic form.” Yet in his silence and despondency he found another language to occupy his mind and heart: art. With pencil, crayon, found paper, matchsticks, and self-made glue, Martín Ramírez created a visual world as compelling and intriguing as any of his artistic contemporaries. His solitary horseback rider, his meandering trains, and his endless dark corridors form fascinating narratives personal and political, whimsical and foreboding.

As Martín Ramírez was Catholic, often drawing images of the Blessed Virgin Mary and rural Mexican churches, his visual world reflects an even greater complexity. Catholicism emphasizes the great dignity of the human person, and in John’s gospel Jesus says, “I came that they may have life, and have it abundantly” (John 10:10). Artistic expression can become a means by which true personhood is shared.

What form does abundant life take for someone in a state hospital, far from home and struggling with mental disease? For Ramírez and those who love his artwork, abundant life appears in the form of drawings that liberated and engaged him in the midst of life’s challenges. Strikingly, the results of this life spent engaging creativity can now be seen around the world in major museums that proudly display his drawings.

Such renown would have likely surprised the young Ramírez, a rancher who grew up in Tepatitlàn, Jalisco, Mexico. Not much is known of his life. Born in 1895, he worked a hard life in rural Mexico. Married in 1918 to María Santa Ana Navarro Velázquez in Immaculate Conception parish in Jalisco, the couple had four children. After acquiring his own farm, he sought economic opportunities in the United States, moving to El Paso, Texas in 1925.

There he gained employment working on the ever-expanding railroad systems. Some of the money he earned from this endeavor was sent back to support his family and pay for the family farm. Sadly, over time, the social and political unrest that culminated in the Cristero Rebellion made it almost impossible for Ramírez to return to Mexico. He received word that he had lost his farm and livestock due to the violence running through his native land. He also received disheartening and confusing information about his family. Add to this the financial disaster that then struck the United States in what came to be called the Great Depression and you have a perfect storm of tragic circumstances.

The facts are sparse and the conjecture great during this period in Ramírez’s life. What is known, though, is that he was given a psychological evaluation in 1931 and, due to his condition, was placed in Stockton State Hospital.

For the next 30 years Ramírez lived in state hospitals. He spoke little and dedicated himself to his artwork. It was through encounters with medical personnel, psychologists, and artists that some of his work initially came to public awareness as artwork from someone with a mental illness.

Many find this classification terribly limiting since art should never be reduced to a personal biography. Indeed, there are numerous profoundly significant works of art from cultures around the world of which nothing is known about the personal lives of the artists. Nevertheless, we are often drawn to compelling life stories. And when we see Ramírez’s long train tracks stretching across expansive landscapes or horseback riders brandishing pistols, it’s difficult not to wonder how his life story may have inspired them.

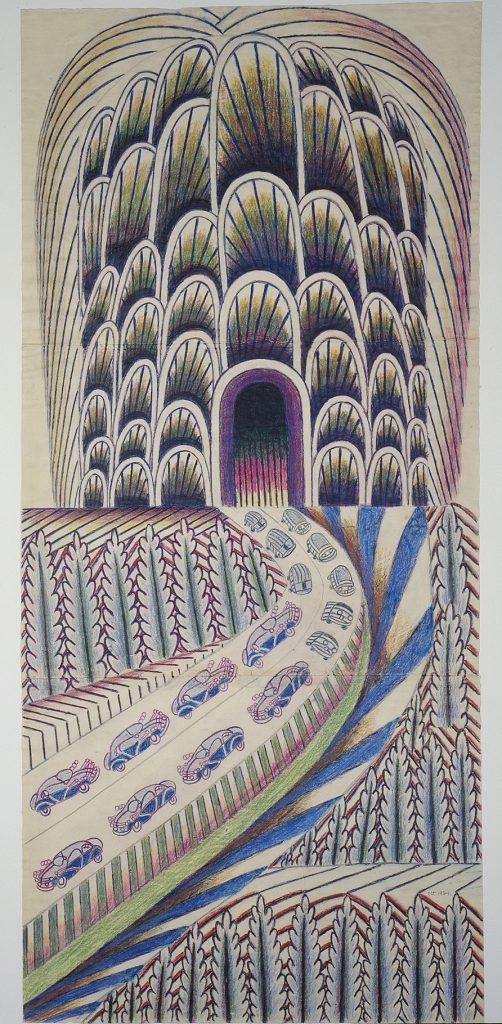

Yet, the art of Martín Ramírez is striking not just in subject matter but also in style. And the centerpiece of his distinctive style is his line. Bold, confident, and precise, Ramírez’s lines are both architectural and organic. At once playful like Alexander Calder’s and measured like Agnes Martin’s, his emphatic parallel lines create mountains, tunnels, archways, and decorative patterns. Artistic worlds are created by these dark repeating lines, places both expansive and confining. These spaces are inhabited by a cast of unusual and repeating characters and motifs.

Perhaps one of the most delightful characters in Ramírez’s oeuvre is the horseback rider. Galloping through unusual landscapes, perched atop seemingly floating pedestals, or staring incredulously at the viewer, these horseback riders are charming. And yet, like so many of Ramírez’s images, there is ambiguity and a subtle unsettling quality about these riders.

The horseback rider with a bugle is a good example. In this series of drawings we encounter a horseback rider with hand raised and blowing an oversized bugle. However, from drawing to drawing the instrument grows like Pinocchio’s nose. In fact, the bugle increases to such size that it overshadows even the horse and rider. The ridiculous size certainly strikes a comedic note, especially as the horse often appears to be almost dancing along to its roar.

However, the comedic tone has a dark side. Bugles are most often associated with the military. Its loud blast can proclaim violence and conquest. It cracks the silence. Increasing the size increases the magnitude of the message. Is this a scream to be heard? Is it a shocking jolt from the calm of everyday life? Is it a warning of impending violence? Don’t be deceived by the frolicking animals; Ramírez’s whimsy is not naïve.

Consider Ramírez’s magnificent drawing Untitled (tunnel with cars and buses). Here the manicured landscape of identically shaped and colored trees lines the gentle sloping highway. The candy-striped berm twists as our eyes are led to a towering emerald city with radiant green arches. The cookie-cutter automobiles patiently clip along at evenly spaced intervals.

But where are the cars going? This yellow brick road terminates in a dark, ominously illuminated tunnel. What’s more curious is that it seems the city is barred. So is this a traffic jam in paradise? Is it a beautiful city beyond reach? Or does the frightening tunnel tell us it’s all just a façade? It’s tempting to ponder whether this image represents the immigrant experience of failed dreams and rejection. Again Ramírez’s masterful ambiguity makes any definitive interpretation difficult, but he nonetheless stirs much deeper thought than at first glance.

Certainly much more can be said about Ramírez’s other motifs: determined locomotives climbing steep inclines, the sad and seemingly endless dark corridors, and the majestic galleons setting out to sea. But most intriguing is the role religion plays in his artwork. While a resonance with Catholic social teaching can be found in the pathos of the solitary horseback rider, possibly victimized by war, or the barred gates of the magnificent city keeping people from flourishing and safety, Catholicism becomes an even more literal subject in Ramírez’s drawings of churches, Jesus, and Mary.

Interestingly, in his Untitled (Landscape), which prominently features a church and large cross, much of his characteristic irony and ambiguity is absent. The gentle landscape with its church, trees, and courtyard is seen from a more traditional Renaissance perspective, unlike most of Ramírez’s other drawings that invent their own twisting and contorting perspectives. This

is a rare drawing in which the sky can be seen, offering a reprieve from his often closed-in spaces. There is a peace and tranquility about this image not frequently found in Ramírez’s work. A peace possibly brought about by a house of prayer and faith.

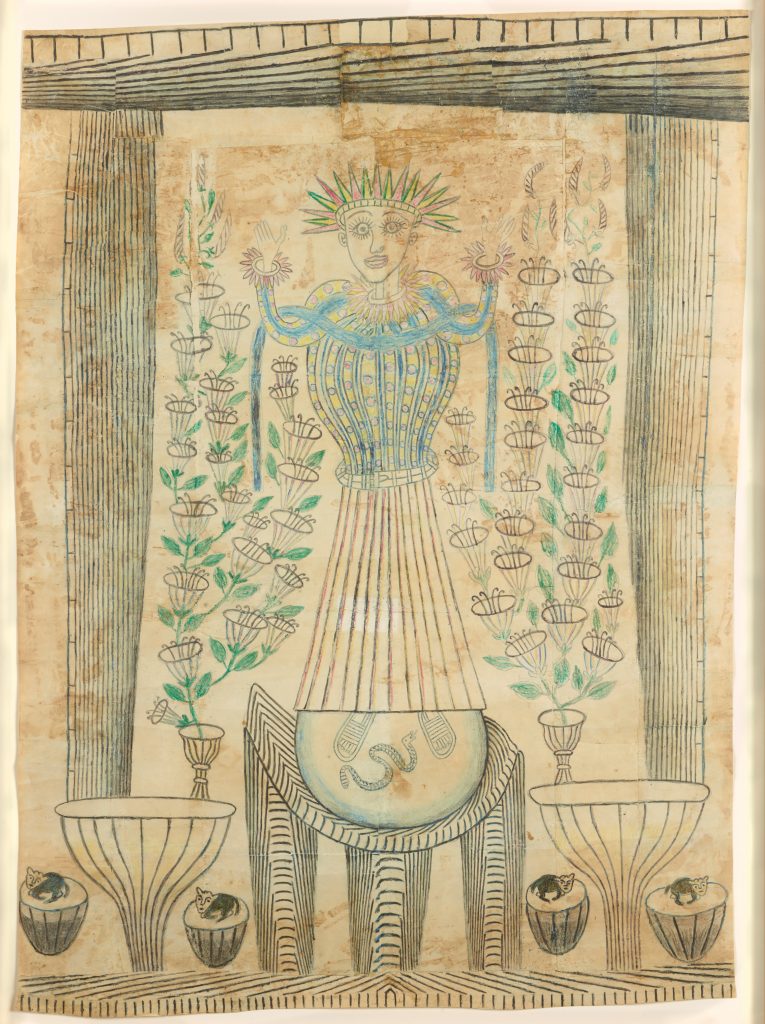

Additionally, this drawing, like many of his artworks, utilizes a stage-like centerpiece framed by decorative abstract elements. This calls to mind many of the reredos and retablos in homes and churches in Mexico and the American southwest. The devotional folk art retablo brings images of the saints into the home for honor, prayer, and intercession, allowing for a deeper relationship with a saint.

This device is employed at times in Ramírez’s depiction of Mary. Indeed, Mary figures more prominently in Ramírez’s work than does Jesus. She is rendered numerous times. Crowned and clothed in decorative garb, she stands atop the world as queen. In Untitled (Madonna) she is depicted as a queen in stage-like retablo fashion.

Flowers bloom in her presence. Her lively gaze embraces the viewer, perhaps acknowledging her intercessory prayers and devotion. A glimmer of hope shines through in these religious and devotional images. Perhaps Ramírez drew images of Mary as his own personal retablo and a source of devotion and encouragement. Interestingly, however, in many traditional depictions of Mary she stands upon a snake, conquering sin and evil. In Ramírez’s images of the Madonna, the snake is still free. Sin and evil still have their way in the world. This is not yet heaven.

St. Irenaeus once shared the remarkable insight, “The glory of God is the human person fully alive.” Martín Ramírez’s journey to full and abundant life was perhaps as long and arduous as the meandering trains he depicted wandering the desert. However, art itself seemed to be the life-giving gift that brought liberation in his wilderness. Art was his means of engaging the world he lived in, and his faith was woven into the images he created.

In today’s art world, where high-profile artists employ numerous studio workers to manufacture polished, big-concept art, Martín Ramírez’s intimate, hand-crafted drawings seem all the more human. They are like an antidote to the impersonal forces in our world, reminding us that the spirit is always free.

This article also appears in the August 2016 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 81, No. 8, pages 22–26).

Add comment