He advised us to do this in complete silence to help our concentration and not disturb our neighbor. After the video was over, he said the correct answer was 12 straight passes and 2 bounce passes. Then he asked, “Did you see the gorilla?”

There must have been 200 of us in the room who had earned a bachelor’s degree from the same prestigious university, and we did not know what he was talking about. So he showed the video again. This time we clearly saw a student dressed in a gorilla costume walk into the scene, beat its chest in gorilla fashion in the midst of the two basketball teams, and then walk off the court.

His research demonstrated that when we are focused on a task, our brain will ignore and exclude everything else. I took it as a parable about our Christian life: If we really concentrate on Jesus and the kingdom of God, we will not see the many gorillas that clamor for our attention.

When I came home and recounted this experience to my community, one of our novices pointed out that the professor had directed us to watch the video in silence, and this aided us in concentrating. She asked, “Who will do this for us, so that we are reminded to focus on Jesus?”

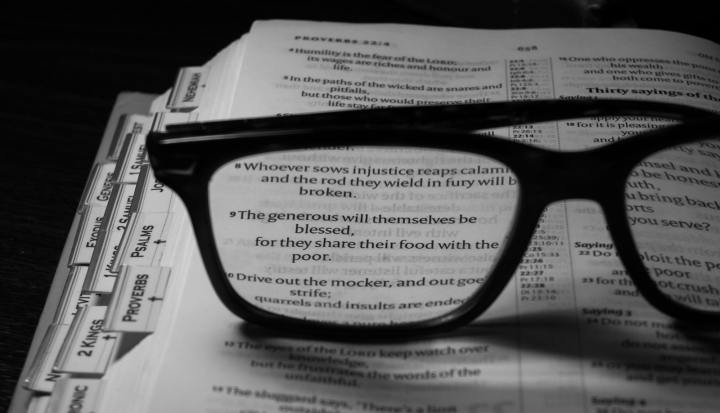

I answered that our practice of lectio divina (meditative reading) should remind us each day to keep on the path as we journey toward the kingdom. Every page of scripture can speak to us of Jesus and keep us aimed at the goal he preached.

Lectio divina is one of the mainstays of the Benedictine day. As novices we were trained to spend 30 minutes each day on scripture and an additional 30 on another spiritual book. I admit I did not take to it right away, and I still struggle (after 26 years) with the discipline of spending quality time with scripture. With words coming at us from every direction at work, in school, or online, it can be difficult to slow down and read meditatively and feel OK if we do not even finish a passage.

I have on occasion been stunned by a line of scripture—often taken out of context—that has been so appropriate to my situation that it was like an e-mail from God. It can also happen when we read other words with the expectation that God has a message for us and we are open to whatever form that “word” might take.

Once on retreat I was grieving a relationship I didn’t want to end. I was reading a book on the monastic vows. The insight came from an unexpected place—not in the chapter on chastity and friendship but in the chapter on poverty. Our poverty consists simply in our not having what we want, wrote the author.

Suddenly it was obvious, and I saw that I needed to accept that in my poverty I could not have this relationship, that being poor with the poor Christ meant not grasping after even immaterial things but remaining dependent on God. If contact with this person is granted me, it will be as a gift, and I will (I hope) be disinterested and unattached. It was a big turning point for me, and I ended the retreat in peace, confirmed in my vocation.

A friend of mine picks out one word from the gospel at daily Mass and repeats it during her day. I have tried this recently, with surprising results. These were my words-of-the-day during a recent week: quiet, deep, old, rub, touch, stretch, your.

The image of the apostles rubbing ears of grain to get something to eat on the sabbath led to other images of rubbing: If you rub a lamp, you might get a genie. We rub silverware with polish to make it shine. In order to rub something, you hold it in your hand. So I resolved to “hold” each event of the day and “rub” it to see what it might produce: something to nourish me or a mysterious personality or a flash of brilliance to marvel at.

The man who stretched out his withered hand (which took some courage) brought to mind other images of reaching out: Michelangelo’s finger of God touching Adam, St. Thérèse of Lisieux grasping both the red rose of martyrdom and the white rose of purity, St. Thomas the apostle putting his hand into the still-open side wound of the resurrected Christ. Do I have the courage to allow God to stretch my capacity to meet others with an open hand and an open heart?

According to St. Benedict, lectio divina has its place beside prayer and manual work. Separately and together, each is meant to direct our steps on the path of the gospel and bring us closer to God. Even in a busy workday, it is well worth setting aside five to ten minutes a day to send and receive e-mails from God.

Regular lectio is like water dripping on stone: eventually the word will penetrate our inner depths. It is one way to deal with the many gorillas who are ready to distract us from the one thing necessary.

Word by word

The classic ”steps” of lectio divina were described by Guigo the Carthusian in the early 12th century.

Lectio: Read. Select a passage of scripture and read it slowly, savoring each sentence and each word. Read until a word or a phrase speaks to you.

Meditatio: Feed. Stay with that word. Repeat it to yourself as you let it sink into your body. Let it become part of you. Repeat the phrase throughout the day when your mind is free.

Oratio: Plead. Let the meditation enter into your relationship with the God of love and become a prayer. Prayer has many incarnations: pure adoration and wonder, thanksgiving for moments of grace, asking for forgiveness and healing for oneself and others.

Contemplatio: Cede. There can come moments when your prayer leads to an experience of union with God. Give yourself over to them, and when the moment of intense peace and silence is over, it remains as a treasure that can be savored later.

This article appeared in the June 2011 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 76, No. 6, pages 47-48).

Image: Flickr cc via Bobby McKay

Add comment