Bob Dylan is an old man now. But even when he was young he was suspicious of “youth culture.” In 1967, while his audience plunged into Vietnam protests and psychedelia, Dylan returned to his original inspiration, “the old weird America”—a term coined by critic Greil Marcus for the pre-pop-culture world of medicine shows, hobos, and old-time music. With the musicians who became The Band, Dylan hunkered down in a rented house in upstate New York and cut a collection of songs that were raw, timeless, and, yes, weird.

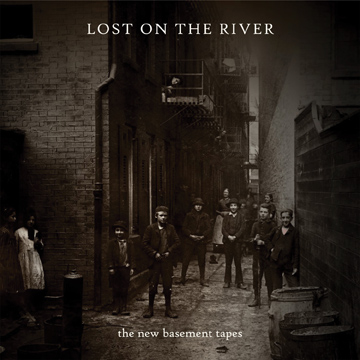

Bob Dylan is an old man now. But even when he was young he was suspicious of “youth culture.” In 1967, while his audience plunged into Vietnam protests and psychedelia, Dylan returned to his original inspiration, “the old weird America”—a term coined by critic Greil Marcus for the pre-pop-culture world of medicine shows, hobos, and old-time music. With the musicians who became The Band, Dylan hunkered down in a rented house in upstate New York and cut a collection of songs that were raw, timeless, and, yes, weird.An excerpt of those sessions, The Basement Tapes (Columbia), was released in 1975 and a complete six-disc collection came out last year. But there was more. In 2013 Dylan’s publisher approached legendary producer T Bone Burnett with a notebook of handwritten lyrics from the Basement Tapes era. Burnett assembled a supergroup of roots-oriented singer-songwriters—Jim James (My Morning Jacket), Taylor Goldsmith (Dawes), Rhiannon Giddens (Carolina Chocolate Drops), Marcus Mumford (Mumford & Sons), and an older outlier, Elvis Costello—to turn the notebook into an album. Lost on the River is the result.

Dylan’s lyrics take place in a world that, as we hear in “Diamond Ring,” had knife sharpeners and organ grinders working the street. Two of the songs (“Spanish Mary” and “Hidee Hidee Ho,” which appears in two versions with two different tunes) toy with old British Isles ballad conventions. Some of the lyrics seem sketchy or even unfinished, but the artists were so inspired by cowriting with a legend that they threw everything they had into producing some of their best work. Lost on the River may not be the historic event some of the hype has suggested, but it is a happy footnote to a saga that brings Dylan’s vision of rooted authenticity to new life in the digital era.

This review appeared in the August 2015 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 80, No. 8, page 42).

Add comment