We were called Immaculata. We were called Concepta. We were called Chrysostom, Eusebius, and Stanislaus, after a Polish boy-saint. We were called Bernard, John, and Thomas after our fathers and Theresa, Elizabeth, and Maureen after our mothers. We were called Paul Kathryn and Robert Rita, pleasing both parents. We were called Serena, signifying calm dispositions. We were called Seraphine, trusting an angelic nature would ensue. We were called Jerome, after a crotchety biblical scholar.

Some names were poor fits. One called Jerome preferred sheet music to Bibles. Her inner-city glee clubs were legendary, the yearly recipients of national titles. Another named Magdala was innocence personified.

These names were formally given to us the day we walked two by two down the long, marble aisle of the motherhouse. We were dressed as brides with veils over our eyes, no grooms in sight, and futures unknown. Oblivious to the majestic organ and the vast choir of nuns’ voices, we glided in a shimmering storm of white, sweeping past the pews, past our gasping families, past the life we had known.

The local bishop in his ceremonials indicated the beginning of our new lives by announcing our new names. We were called Athanasia, Laurentia, Alfred, Brigada, and Ancilla, meaning handmaid. Ecce ancilla Domini, we said. Behold the handmaid of the Lord. We were called Joan of Arc, who was burned at the stake by clerics one year and declared a saint the next.

When the opportunity came, we returned to our baptismal names. We were called Bernadette, Rose, Renee Marie, Peggy, and Janet. We were called Michelina after our father’s mother who died at his birth. We were called Sister.

Our fathers were factory workers. Our fathers were onion farmers and dairy farmers. Our fathers were horseshoe pitching champions. Our fathers were proud of us. They kept holy cards in their wallets that said, “I’m the Daddy of a nun.” Our fathers were butchers. Our fathers mined marble in Vermont hills. They lost fingers to merciless machines.

Our fathers were photographers for the NYPD. Our fathers abandoned their families. Our fathers were undertakers and mailmen. They were professors at prestigious universities. Our fathers were pole vaulters in high school. They vaulted for joy over the bushes around our homes. Our fathers were dentists. Our fathers were alcoholics. Our fathers were pediatricians. Our fathers dropped dead in front of the TV. Our fathers died in nursing homes. Our fathers died in our arms, and we never quite recovered.

Our mothers were office workers at gated arsenals. Our mothers were homemakers. Our mothers pasted gussets on pocketbooks in sweatshops. Our mothers sat atop the hood of the family car while our adoring fathers took snapshots.

Our mothers were seamstresses and shop owners. Our mothers lived with us and our siblings in one city, while our fathers practiced law in another city 80 miles away. We reunited in the summer. Our mothers were teachers. Our mothers were violinists. Our mothers made their debuts in Carnegie Hall.

Our mothers slept on the floor next to our sick beds lest the fever claim us. Our mothers were born to be mothers, hoping one day to be called Mammone, Grandma. They dreamed of those grandchildren their celibate daughters would not be giving them. Our mothers kept our pictures in bedroom shrines. Every day they looked at us in our religious habits, so beautiful, so holy. Our mothers figured they had a direct line to God.

When we entered the convent, we were each given a small white bed in a large white dormitory. At night we disrobed under white nightgown tents, our earthly garments falling in a pool at our feet. We lay in identical beds, each surrounded by thick white curtains to form a small white space called a cell. When the lights went out, black bats squealed, darted from hideouts, and swooped over the beds.

It was the same small, narrow bed in every convent we lived in, always provided by the pastor. The beds faced the red brick wall of the church. The beds faced gas stations, laundromats, and grocery stores. The beds were situated 100 yards from the railroad tracks. At night we watched travelers eating and drinking in well-lighted cars, a blur of hands lifting forks and wine glasses. Sometimes in our single beds we dreamed about the lives these bright people led, their beautiful homes, the laughing children leaping into their arms, the tall, smiling husbands.

We slept in large, old-fashioned, gabled rooms with stars for company. We slept in modern, efficient rooms. We slept in airy places overlooking lakes and in attics overlooking street fights. We wallpapered the rooms with roses. We painted green vines on the walls above the beds.

One by one the convents closed. In no time they were converted into homes for battered women, retreat centers, catechetical schools, and libraries. The ghosts of the Sisters who died in the convents roamed in dismay from room to room. The convents we left were turned into soup kitchens, credit unions, and parking lots.

Undaunted, we carried the beds wherever we were needed. We slept in shotgun houses on migrant farms. We slept in low-income apartments for seniors. We slept above Chinese restaurants, drugstores, thrift shops, and saloons. We slept in trailers parked in remote rural areas and in the back rooms of the clinics we ran. We slept above funeral parlors and answered night calls. During the day we comforted the bereaved and prayed with them at the cemetery. When the rectories closed, we moved in, became church administrators, and slept in double beds.

All of the rooms we lived in were borrowed. In every house there was a small gold box where Christ lived, so that to recover the box was to hear intimate conversations.

We filled our souls with His Gospel. We filled our souls with the lives of the saints and the lives of the people. We filled our souls with the holy rule and Shakespeare, the Beatitudes and Chopin. We filled our souls with Mary’s rosary, the joyful and sorrowful mysteries of her life overlapping ours. We repeated her son’s name for a mantra as we walked the streets and hospital corridors. We called God “my Sweet One.” We said that God had the truest part of our hearts.

In run-down neighborhoods we fell into sewers where we treaded water until help came, like our mothers had taught us. We fell off roofs at Habitat for Humanity buildings. We fell down dark stairs in religious ed centers and were left crippled. We fell from favor when we changed into secular dress. We fell from grace and helped each other to rise.

We ran in sweats with an Olympic torch held high and our veils blowing, and we did not fall. We ran marathons and held hands as we crossed the finish line. We ran from God, who dogged us down the labyrinthine ways of our own minds. We ran for public office and had to leave our communities. We ran across sunny beaches with our arms extended into the joy of the day. We ran with arms extended into the arms of the ones we would marry. We ran from a church we no longer believed. We said, “Life is an Olympic event.”

We said that our Olympic medals were the profession crucifixes we received the day we vowed poverty, chastity, and obedience. These crucifixes won us entry into sick rooms and jails, weddings and funerals, board rooms and huts.

We ran with them to South Africa to serve and discovered that Christ had got there before us. We stomped dirt floors with brightly clad women, their bare breasts bobbing to native beats, their babies strapped to their backs. Off in the distance, mountains of gold dust glistened in the scorching sun.

We ran to Central America, were captured and chained in small flotillas plowing swampy waters. We were seen on American television by our distraught communities. They saw us crouched low in the boats and heard the bullets flying over our heads.

In South America we ran from guerillas who ran us down with machetes. Our bodies were shoveled into shallow graves. Our bodies were removed by those who loved us and placed in honorable graves outside poor churches. Our bodies were marked with Christ’s cross.

The Body of Christ rested on our tongues so that we spoke with the voice of angels. We spoke with the voice of teachers. We spoke with the voice of founders, poets, and catechists. We spoke with the voice of scientists discovering ground-breaking cures. We spoke with the voice of preachers and midwives, artists and organic gardeners. We spoke with the voice of healers, anointing the sick and closing their eyes at the last. In scrubs, we stood with doctors before the bodies of organ donors and said, “Thank you for the gift you give that others may live.” We spoke with the Body of Christ on our tongues.

The Body of Christ rested in our bodies. The Body of Christ remained intact through violent martyrdoms. The Body of Christ was untouched by mastectomies, brain surgeries, the amputation of fingers, feet, and legs. The Body of Christ was never mutilated, no knife touched the Sacred One. Lying in the killing fields, on the surgeon’s table, the acupuncturist’s bed, we said, “My body holds the Body of God.”

At the finish line we held each other’s hands, kissed each other’s brow, and wept. We said, “Into your hands, O Lord, we commend her spirit.”

We gave our bodies to science. We gave our bodies to the fire. We gave our bodies to the earth from whence they came. And the earth received them. The earth remembered.

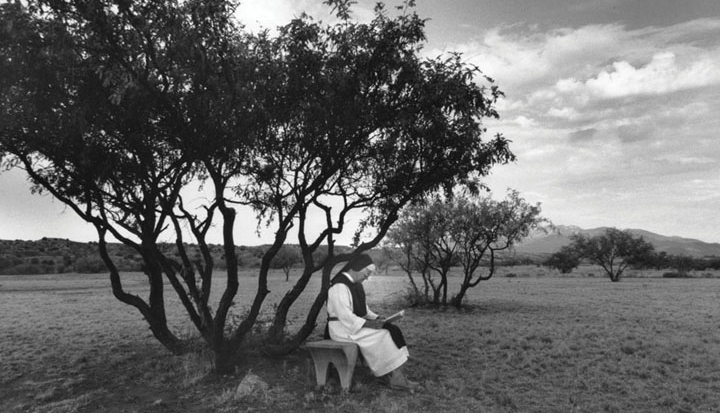

Early mornings the sun lights up the dewy grass so that it shimmers. Each blade of grass holds a tiny globe of light on its tip. We were those globes, divinely lit. Each new day we held our lights aloft. Together we moved over the fields, up the hills, down the valleys, and across the earth. Such a shine of gladness was in our hearts. We were called Sisters.

This article appeared in the January 2013 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 78, No. 1, pages 35-37).

Image: Paul Conklin

Add comment