Editors’ note: Sounding Board is one person’s take on a many-sided subject and does not necessarily reflect the opinions of U.S. Catholic, its editors, or the Claretians.

Religious art should challenge and inspire our lives of faith—not put us to sleep.

A number of years ago my provincial superior appointed me to a committee charged with developing a monument for a new burial plot for the friars of my Franciscan community. After spirited discussions about the statement we wanted to make, meetings with a sculptor, and the approval of our provincial leadership, we met with the administration of the diocesan cemetery.

After reviewing the drawings and model, the director, a priest, told us our proposal was “unsuitable” and could not be installed. In an attempt to explain what would be acceptable the assistant director advised us to put up “a cross, a lily, or a lamb.” In the end, to satisfy the cemetery officials, we agreed to add a cross to each corner of the monument’s low pedestal. (Yes, a cross on just about anything will christianize it.)

In the committee’s mind, we had proposed a simple representation of the dying and rising of Jesus. Though I viewed the design as bland, the cemetery administration found its abstract nature provocative. It was clear who would judge our plan; the director of the cemetery informed us that “I’m the pastor here, and what I say goes.”

Enter any Catholic institution today—a church building, school, or hospital—and you will mostly likely encounter art selected from a catalog. The offerings from such sources typically replicate representations from another era with updated materials. Most of them resemble something you’ve seen before. Are you still thinking about these artworks a month later? I would venture that, in the majority of cases, the answer is “no.”

Rather than selecting artworks for the ways they can inform our lives of faith, what we choose is an object that fills up a space with a nostalgia too often justified as “traditional.” But rather than harkening back to a fabricated sacred tradition, we should call catalog-style art what it most often is: dull, saccharine, wishy-washy.

Describing what makes art appropriate, the U.S. Catholic bishops’ document Environment and Art in Catholic Worship notes that works of art “must be capable of bearing the weight of mystery, awe, reverence, and wonder.” That’s a tall order, one rarely realized.

We put up a cross, a lily, or a lamb with little thought because, when all is said and done, we really don’t expect art to make a difference in anyone’s life. Would we tolerate a preacher failing to give a homily because the scriptures are something we’ve all heard before? Not every homily makes a difference in our lives, but we remember the ones that changed us, challenged us, and comforted us. Why don’t we demand the same thing from our religious art?

For centuries the church was the principal patron of the arts. When people go to Europe, they visit churches or museums filled with art that used to be in churches. The Second Vatican Council’s Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy notes: “Very rightly the fine arts are considered to rank among the noblest activities of man’s [sic] genius.” But the American church largely reflects a culture that does not value or understand the place of the arts in either communal or individual life. Funding for the arts is what our states, cities, and schools eliminate to balance their budgets.

A cross, a lily, or a lamb uses familiar language, disturbs no one, proposes nothing new. But art’s function is not endless repetition of what we already know; art should, in part, help us discover something new, deeper, or more complex. If it doesn’t stretch our thinking, touch on our experience, or nurture our faith, why have it around?

As a college student, I joined my classmates in making fun of a statue of Mary in the college chapel. Lacking the prepubescent modesty of body that most images of Mary possess, this Mary was clearly a woman—an older woman who had lived long enough to be wise (and to have seen her son crucified) and who was not going to win any beauty contests. This statue features enormous hands out of proportion to the rest of her body. My classmates and I took delight in mocking these attributes.

Today, as I wonder how I need to be open to God’s will, I remember the statue’s large, open hands. Nearly 40 years later I get both what Franciscan Tom Brown tried to communicate in his hand-carved wooden statue and how the best of art can function in church life. That sculpture of Mary continues to instruct me about the Christian’s attention to God’s grace.

For many believers, contem-porary art is something to be avoided. Unfortunately, because of most people’s unfamiliarity with current art production, a few well-publicized works of art have formulated our dismissive attitude. But, as Environment and Art in Catholic Worship puts it, “contemporary art is our own, the work of artists of our time and place, and belongs in our celebrations as surely as we do.”

Contemporary art can be risky. If a work loses its force in a few years or decades, what do you do with it? When the city of Chicago installed a large Picasso sculpture downtown in 1967, nearly everyone poked fun at the work and many hated it. Now, more than four decades later, it has become a beloved and treasured icon. If a faith community does its homework and works with a knowledgeable consultant, dignified and stirring art can be brought into the life of the community. But it is easier to open a religious goods catalog.

A recent church commission that has negotiated the issue of contemporary art well is part of the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels in Los Angeles. John Nava’s 2002 multi-element tapestry entitled Communion of Saints lines the nave. Though the woven cloth format has been used for centuries, and religious art has often featured one or more saints, this work reads as current and enduring.

Utilizing the ancient device of a procession of saints (typical of the Byzantine-era churches of Ravenna, Italy, for example), Nava arranges the saints into groupings and uses their body language to direct worshippers to the altar and ambo. Installed low enough so that any view includes part of the assembly during the celebration of the Eucharist, they join us and we join them at the Lord’s table.

To accurately depict the saints’ ethnicities and to ensure these saints look like real people, Nava photographed real faces. Thus, St. Augustine of Hippo actually looks like a North African. By focusing upon a truthful portrayal of those the church has identified as holy, Nava reminds us that we are a multicultural church and society. He also included unnamed saints as a reminder that holiness is our common vocation as followers of Jesus.

How do we improve the quality of our religious art? Here are four ways:

Buy less art. Parishes spend money on art, but the budget allows the purchase of five green vestments, three statues, and votive candle holders in six colors. Because every religious institution has multiple demands on its limited funds, finding more money is an unrealistic solution. Instead, use care to acquire fewer pieces of superior art. Good art, the cathedrals of Europe remind us, takes time to be funded.

Use temporary art. Any arts program should include the work of the local community. Hang up the kindergarteners’ drawings, use seasonal banners made by parishioners with competent supervision, and exhibit the community’s artists. Such a program can help mark the rhythm of the year and reverence our common desire to express our encounter with the holy.

Educate, and seek out the educated. A higher price tag does not mean one object is more suitable or finer than another. Any informed art choice entails thoughtful discussion and educational opportunities—both before and after a choice is made. Identifying people who possess the ability to instruct others about quality and appropriateness is key. If no one comes to mind, consult the diocesan worship office.

Be clear about the decision-making process. The process of art selection must include an awareness of the needs of the local community, an understanding of how art functions, and an honest discussion of individual tastes (which is different from quality). Who makes the decision about acquiring a particular artwork for a specific community needs to be addressed.Don’t be afraid to talk about who is competent to make this selection and the process by which it will be made.

Creating a space that engages all of our senses will encourage a community to express and continue its faith journey. With a tad more attention, energy and resources, the visual arts can become a vibrant part of the life of the American church.

“And the survey says…”

1. Religious art should be provocative rather than safe and get me to notice it.

62% – Agree

16% – Disagree

22% – Other

Representative of “other”:

“Engaging art would be more to my liking. Provocative art could be off-putting, not inspiring.”

2. I think visual art is animportant component of Catholic spirituality.

95% – Agree

3% – Disagree

2% – Other

3. My parish supports local artists.

45% – Agree

55% – Disagree

4. I tend to like religious artwork from the past more than modern religious art.

41% – Agree

31% – Disagree

28% – Other

Representative of “other”:

“Both past and present religious art have the ability to speak to the soul.”

5. The church in the United States missed the boat by not becoming a patron of the arts.

70% – Agree

15% – Disagree

15% – Other

6. I find the artwork (windows, statues, paintings, stations of the cross, etc.) in my parish to be:

44% – Beautiful.

40% – Inspiring.

33% – Generic.

30% – Unique.

29% – Boring, bland, or too safe.

28% – Old-fashioned.

14% – Modern.

10% – Ugly.

5% – Daring.

7. Parishes should spend more money on less, but better, art.

80% – Agree

9% – Disagree

11% – Other

8. My parish has commissioned a new work of art in the past 10 years.

35% – Agree

43% – Disagree

22% – Other

This article appeared in the January 2011 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 76, No. 1, pages 23-27).

Results are based on survey responses from 94 USCatholic.org visitors.

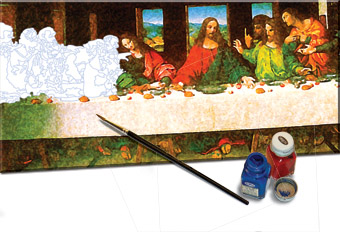

Image: Photo illustration by Tom Wright

Add comment