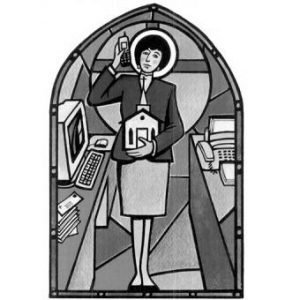

Scratching the stained-glass ceiling, an increasing number of women hold leadership positions in the church. Here’s a look at the gifts they bring and the challenges they face.

Scratching the stained-glass ceiling, an increasing number of women hold leadership positions in the church. Here’s a look at the gifts they bring and the challenges they face.

It is lunchtime on a Thursday, and Sharon Daly, vice president for social policy at Catholic Charities USA, talks hurriedly on her cell phone, the buzzing chaos of Washington’s Union Station in the background. Daly, the first woman to occupy this position, squeezes a phone interview in between legislative meetings on Capitol Hill, with the future funding of programs like Section 8 housing and Head Start at the forefront of her mind.

A 25-year veteran in the field of legislative advocacy, Daly recalls feeling a little out of place at the 1984 bishops’ meeting, the first she attended during her tenure in the public policy arm of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB). “There were hardly any women there. I just remember looking out into this sea of 300 white heads and gold chains,” she says with a laugh. Despite her minority experience, Daly has never looked back. After holding a variety of legislative advocacy positions, she has devoted the past nine years to Catholic Charities’ advocacy work on welfare reform, tax issues, and the federal budget.

Daly is but one in an expanding group of courageous, intelligent women leaders in the U.S. Catholic Church, women who have been named to top-level executive church jobs in the traditionally male-clergy-dominated areas of personnel, property, and policy.

These highly-educated women, most of whom have served the church loyally for decades, are the first women to hold positions such as chancellors, personnel directors, and pastoral administrators. Though they embrace a collaborative leadership style that resists self-promotion, these women are not the type to shy away from “firsts.”

Mary Edlund, 55, the first female chancellor of the Archdiocese of Dallas, began her post with the daunting task of regaining the laity’s trust after a major clergy sex-abuse crisis in 1997. Carol Fowler, 61, the first female director of personnel in the Archdiocese of Chicago, proudly recalls when Cardinal Joseph Bernardin asked her to take the position in 1991.

Valerie Chapman, 53, pastoral administrator at St. Francis of Assisi Parish in Portland, Oregon, stood in the designated pastor’s space in Portland’s cathedral as the archbishop confirmed her parish’s high school students. Dolores Leckey, a senior fellow at the Woodstock Theological Seminary in Washington, D.C., now welcomes young women theology students into her office for informal mentoring sessions, drawing upon her rich 20 years of work experience as founding director of the Secretariat for Family, Laity, Women, and Youth at the USCCB.

Though most U.S. Catholics would not be surprised to learn that women comprise 83 percent of those engaged in parish work, many are not acquainted with the increasing number of women who hold high-level administrative church positions in dioceses, social service agencies, and faith-based organizations. These pioneering women carry with them an enormous amount of decision-making power by virtue of the positions they hold.

Daly, Edlund, Fowler, Chapman, Leckey, and many women like them are changing the face of the church’s leadership. Their stories tell not only of the rich gifts and unique leadership styles that women bring to the church, but also of the challenges that come with being a “first” in anything.

A spirit of collaboration

Many women bring a collaborative leadership style into organizational structures that have traditionally operated hierarchically. “I used to teach math,” says Fowler. “I treat issues like a word problem and try to be a problem-solver by working with others. Sometimes this means that I’ll decide more slowly. If I have a disagreement to deal with, for example, between [religious educators] and principals, I’ll pull together a committee to look at the problem.”

Sister of Mercy Sharon Euart, 58, a canon lawyer in Silver Springs, Maryland, agrees that for many women leaders the decision-making process is as significant as the decision itself. “Women tend to be more attentive to things like process and dialogue. This can extend the decision-making process but can generate ownership, understanding, and support.”

But Daly doesn’t see this style as unique to women. “Before I saw a lot of leaders I assumed that collaboration was unique to women. Now that I have worked with lots of leaders I’m not convinced that’s the case. Collaboration does not come any more naturally to me than to my male counterparts,” she says. But collaboration is essential for influencing legislation. “It’s a complex dance,” she says. “You have to have relationships with both allies and opponents. The best leaders in this line of work are people who are collaborative. It doesn’t matter if they are male or female.”

Leckey found a collaborative leadership style helped in her work with the USCCB because “I wasn’t competitive with the bishops like some men were. Many of them had gone to seminary together and suddenly one of their classmates was named a bishop, and one of them would be thinking, ‘Well, I was smarter in liturgy than he was.’ That wasn’t an issue for me.”

Relationship-building can be a challenge for women church leaders, especially when working with clergy who have access to informal social networks that often exclude women.

During her tenure as the first female associate general secretary at the USCCB, Euart says, “There were times I’d feel left out of the conversation because there had been previous conversations that had taken place at the priests’ residence before work,” she says. “I had to let [the priests] know that while it may have happened unconsciously, it was not helpful to the decision-making process. I learned to adapt to this and looked for more information when it was appropriate.”

Answering the call

The majority of women who now serve in these high-level administrative positions speak out of many years of experience working in the church. Most believe that, in their case, familiarity has its privileges.

This was certainly the case for Edlund, who, in the wake of a major clergy sex-abuse trial, was given the responsibility of reviewing sexual-abuse allegations involving minors, reconstituting advisory review boards, and heading up the priest personnel board, which had historically been composed of all clergy. Edlund, who’d worked for the Dallas archdiocese since 1979, says she definitely “had an advantage in that I already had a good working relationship with the clergy. They were getting a known entity.”

Euart agrees. Being the first female associate general secretary of the USCCB was a challenge, but “I felt that I moved into it smoothly because I was not completely unknown. I felt tremendous staff support and support from the bishops. This was important because one of my responsibilities was to supervise 10 departments, most of which were headed by priests.”

Euart, who has been in church administration for more than 25 years, thoroughly enjoyed her time at the USCCB and was sometimes “in awe of the responsibility I had. I realized that the final ‘yes’ or ‘no’ that a pastor or bishop or superior may give was determined not only by that person’s prudent judgment but by the influence of my perspective on a decision-making process.”

Unfortunately for Euart, being a known entity wasn’t quite enough. In the fall of 2000, after 13 years as the USCCB’s associate general secretary, Euart was asked to leave her post. This was especially painful for her in light of the fact that she was, in the minds of many clergy and laypeople, the leading candidate for the general secretary post itself. When the U.S. bishops asked the Vatican if religious or other laypeople could be nominated for the job, according to a September 2000 article in the National Catholic Reporter, the answer from Rome was a resounding “no.”

The general secretary serves as the day-to-day chief operating officer of the bishops’ conference. Though only priests have held the post since the position’s inception in 1918, canon law does not specify that this high-level administrative position must be held by a priest.

Not only did Euart not get the top job, she lost her job as associate general secretary. “The new general secretary wanted to hire his own staff,” she says. “It was the most painful professional experience I have ever had, and there wasn’t anything I could do about it. This experience is something a lot of women fear. I would have liked it to have been different.”

To say she was fired because she was a woman “would be too much speculation” Euart says (another woman religious was subsequently hired for Euart’s position). She does, however, name shaky job security as one of the primary liabilities for women in church leadership positions.

Jane Bensman, 54, a pastoral associate at Queen of Martyrs Parish in Dayton, Ohio, and the only full-time pastoral staff member at the 500-family parish, experienced her own job security scare when her pastor was removed in April 2002 in the face of a substantiated allegation of sexual abuse. An interim pastor was appointed who was “very difficult,” according to Bensman.

“It was pretty much a mess, and he handled things very inadequately,” she says. “He didn’t want [the staff] to be in charge, even though we really had been the ones who had been in charge all along. We definitely didn’t fit into his mold of how he thought things should be.”

Thankfully, the interim pastor only stayed for three months, and Queen of Martyrs now shares a new pastor with a neighboring parish. Bensman says the new pastor is “someone who works with me like I am an equal, a colleague.”

Despite the loss and difficulties that accompanied Bensman and Euart’s experiences, both stand firm in their convictions they are called to serve the church. “My heart’s desire is finding a way to serve the bishops in this country again,” says Euart, who now serves various dioceses and religious communities as a consultant.

“It was ultimately because of the people that I stayed at the parish,” says Bensman. “I felt that I could provide stability in the transition. I spent a lot of time praying about my decision, and it turned out to be wonderful.”

Euart and Bensman’s deep sense of call to ministry is echoed emphatically by many women administrators. Such anecdotal evidence is bolstered by a March 2002 study by the Leadership Conference of Women Religious (LCWR), the first academic study of women’s experience in Catholic Church administrative roles. The LCWR study, titled “Women and Jurisdiction: An Unfolding Reality,” found that 85 percent of the 426 women interviewed reported a high sense of vocation or calling.

Does this mean that these women feel a call to the priesthood? Are these administrative positions simply the next best thing?

“Ordination has never been an interest of mine personally, but that is not to say that I am not aware of other women who are interested in it,” says Euart. “My gifts are in administration.”

Fowler echoes a similar sentiment. “I don’t believe that God calls you to something that isn’t going to happen,” she says. “But the sense of vocation is very strong in me. My call is the absolute number one, overarching reason why I do this. It comes out of Baptism.”

Though these leading female church administrators enjoy unprecedented access to decision-making power, the introduction to the LCWR study sounds a note of caution and reality with respect to decision-making and ordination: “As long as jurisdiction (the power to govern) is tied to ordination, a very limited number of roles with authority will be open to women.”

Though the number of high-level women administrators is increasing, they are still the exception rather than the norm. In the end, it is by-and-large the ordained clergy who have the final say in major administrative decisions.

The next generation

The average age of women church administrators–59.5 years according to the LCWR study–raises the question of who will carry the torch for the next generation.

For those gathered at a March 2001 first-ever national gathering of women diocesan leaders, recruitment of younger women occupied a prominent place on the agenda.

Sheila Garcia, assistant director of the USCCB’s Secretariat for Family, Laity, Women, and Youth says that she is “terribly concerned that there are not enough younger women in the pipeline. We need to point out to them the number of leadership positions that are available . . . . Many younger women think that because they can’t be ordained there is no way they can have a meaningful role.”

Fowler experiences this dearth of women firsthand, especially when she serves as the only woman on an 18-member advisory council to Chicago Cardinal Francis George. While other women attend the meetings, Fowler is the only voting female member of the council. “We need more women at the higher level positions for their perspective on life, church, and who God is in our lives.”

Other women administrators speak emphatically of the continued need for a women’s viewpoint in the church, and the challenges they face in making that perspective heard. “[It] will not happen unless women get in there and work at it,” says Chapman. “It’s not like going through the seminary, where when [seminarians] finish they will be guaranteed a job.”

Chapman emphasizes the need for older women to mentor younger women “and not to feel threatened by them. With so few leadership opportunities for women available there is a tendency to be protective of the few opportunities that do exist.”

The women also emphasize the importance of putting younger women on a career track by making education available. Results of the LCWR study found that 75 percent of women administrators have a master’s degree; an additional 10 percent have doctoral degrees. Along with education, a high premium is placed on previous work experience. Ninety-four percent of the LCWR respondents said that they had been prepared for their administrative position by a previous church position.

Younger women like Kristi Schulenberg, 31, and Stacey Noem, 27, who currently work in church ministry, have committed themselves to serving the church, but salary tops their list of concerns as they cast an eye to the future. The average salary for women administrators, according to the LCWR study, was $20,000-29,000.

“As a young adult woman, I find it very interesting that many of my friends and I were formed by institutions of Catholic higher education and are doing the work we do because of our experiences there,” says Schulenberg, director of parish social ministry for Catholic Charities USA. “But when you come out of a Catholic university and have to pay off exorbitant loans, how do you do that when you are making 20 grand working for a diocese?”

Stacey Noem, former director of the Family Life Office in the Diocese of Venice, Florida and current master of divinity student at Notre Dame, echoes similar concerns. “I’m worried that I won’t be able to find a job that will allow me to send my kids to Catholic school. Am I going to be able to provide for my family? I want to love my job, but I love my family, too.”

Competitive salaries, mentoring, and opportunities for graduate education and leadership will help ensure that educated, trained younger women will be ready and willing to lead the church in the future.

Mentoring is a high priority for Catholic Charities’ Sharon Daly, who tries “to challenge the people who work for me to grow. I’m just as likely to send someone else from our staff to a meeting on Capitol Hill as I am to go myself.”

Euart says that, despite the professional challenges she has endured, she highly recommends the field of church leadership to women. “If younger women have the gifts, the desire, and the training, and have a love for the church, it is worth a try. Women have to try to find a niche in the structure that currently exists–we can’t lose sight of the fact that this is a hierarchical church, and that isn’t going to change.”

Jane Bensman looks to the future of the church with hope. “The future potential for women will only increase,” she says, “and the field of church ministry will continue to be strengthened because of it.”

This article appeared in the September 2003 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 68, No. 9, page 32).

Add comment