The journey to Kalaupapa, Hawaii has never been easy. The only way to reach the peninsula by land is a three-mile trail that slowly winds its way down the tallest sea cliffs in the world. My first trip was on a muggy day under a hot Hawaiian sun. I trudged through mud and stumbled down slick rocks, trying not to slip into the Pacific surf that was crashing more than a 1,000 feet below. That was nothing compared to those that came before me.

Those towering cliffs, located on the island of Molokai, were once used to quarantine thousands of native Hawaiians suffering from Hansen’s disease, better known as leprosy. When Hansen’s disease was brought to the islands in the early 19th century, it spread like a plague.

Agents from the Board of Health rounded up the sick and herded them onto boats alongside cattle. Some accounts say that they dumped their sick cargo into the waves a few hundred yards off the peninsula and left them to fend for themselves. The first group arrived in 1866 with no food, no shelter, no help, and no hope.

Around the same time, 23-year-old Joseph de Veuster, a novice who took the name Damien upon joining the Fathers of the Sacred Heart of Jesus and Mary, left his home in Belgium to travel to Hawaii. He arrived in Honolulu in the spring of 1864, where he was soon ordained. Damien spent eight years preaching on other islands before learning about the plight of the leprosy patients, and he was first in line to help them.

My own journey to Kalaupapa started shortly after I graduated from the University of Notre Dame last May. I heard about a job in Hawaii and thought I had found paradise.

The job, interning with Molokai’s weekly newspaper, was far from glorious. The weekly stipend of $40 dollars would mean a lot of peanut butter and jelly dinners. Molokai is a small rugged island, virtually untouched by tourism—not the Hawaii of travel magazines. No building is taller than a coconut tree, cell phone service is hard to come by, and chain stores are unheard of. Familiar faces and the only way of life I had known would be 3,000 miles away. Suddenly, I was having second thoughts.

That’s when I discovered Father Damien. I imagined the young priest boarding a ship for a long, treacherous journey to an unknown side of the world. He had never seen a picture of the island or even heard the native language. Equipped with nothing but his faith, Damien blindly made his way to Hawaii and eventually to Kalaupapa.

Once on the island, he immediately got to work caring for the patients’ wounds and building churches, homes, and health centers. Many of these simple buildings are still there today.

Boogie Kahilihiwa, who has Hansen’s disease and has lived in Kalaupapa for nearly 60 years, told me in a deep throaty voice that physical pain and a lack of resources were manageable, but “the most painful part of leprosy is the separation from your mom and dad—from the ones you love.”

Father Damien eased that pain. He helped patients find comfort in the Bible and in one another. The legend of his hearty laugh still brings smiles to the patients’ faces. Along with the physical structures, Damien built a sense of community in Kalaupapa.

As soon as I arrived on Molokai, I was caught up in that same “spirit of Aloha,” which literally means “to share breath.” Neighbors routinely dropped by with gifts of mangos and fresh fish. Strangers invited me into their homes for dinner or simply to “talk story.” In return, I’ve been able to help dig a garden, throw fishing nets, or drag a hose when brushfires crept toward town.

Aloha is a way of life that is native to Hawaii, but no one embodied it quite as well as the short, stocky missionary from Belgium. It is a concept, I’ve realized, that echoes the teachings of Jesus.

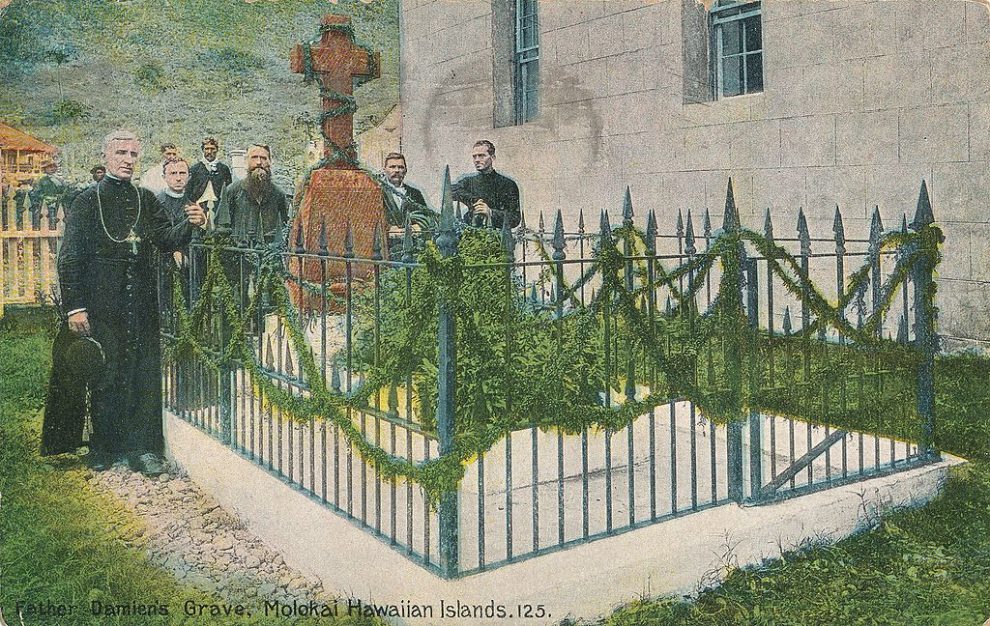

While missionaries were scheduled to stay in the leper colony only a few months at a time, Damien eventually became a part of the community, contracting the disease after spending several years among the sick. He said he didn’t want to be cured if it meant leaving the island. Damien died in Kalaupapa in 1889 after 16 years of service there.

Damien’s courage inspired me to make my own leap of faith and travel to Molokai, but once on the island, his example taught me that there is nothing more powerful than helping another human being. The scenery aside, it’s the people that make Molokai truly beautiful.

Following in Damien’s footsteps doesn’t mean giving up your life to dress leprosy wounds in an unknown land. Spreading his spirit is as easy as lending a hand to your neighbor or just listening to their stories. The only feeling greater than being helped is being the helper.

Add comment